- Scholastic Alchemy

- Posts

- Behavior Management using CW-FIT

Behavior Management using CW-FIT

Showing why the Department of Educaton is Valuable

Welcome to Scholastic Alchemy! I’m James and I write mostly about education. I find it fascinating and at the same time maddening. Scholastic Alchemy is my attempt to make sense of and explain the perpetual oddities around education, as well as to share my thoughts on related topics. On Wednesdays I post a long-ish dive into a topic of my choosing. On Fridays I post some links I’ve encountered that week and some commentary about what I’m sharing. Scholastic Alchemy will remain free for the foreseeable future but if you like my work and want to support me, please consider a paid subscription. If you have objections to Substack as a platform, I maintain a parallel version using BeeHiiv and you can subscribe there.

I thought I would do something a little bit different today. I had planned a post lamenting funding cuts at the Department of Education and, especially, two services they provide for free that can benefit every teacher. One is ERIC, the Education Resources Information Center, that serves as a library of studies selected by the Department of Education because they either represent important research, important educational history, or showcase best practices. You can read more about ERIC’s importance from Jill Barshay at the Hechinger Report. The other service is the What Works Clearinghouse. This is the Department of Education’s attempt to synthesize research findings into practical and easily understood summaries so that teacher can implement research-backed practices in their classrooms. Instead of talking about why this is so important, I thought I’d post today about one approach to exemplify why this is such an important resource.

Class-Wide Functional Intervention Teams

Class-Wide Function Intervention Teams (CW-FIT) are a style of behavior management that explicitly teaches certain skills and behavioral expectations using teams of students in game-like class sessions and positive feedback from the teacher. Studies show that this approach has positive impacts on student behavior and may also hold benefits for teacher practices.

Let’s take a quick look at what CW-FIT looks like step by step.

Teachers identify 4-6 target skills and behaviors they want to see improved. Teachers prep materials for the lesson and the game. Teachers decide how they want to monitor students during the game, set point levels, rewards or prizes, etc.

Teachers teach a brief lesson about those skills, defining them, explaining their importance, and giving an opportunity for students to practice each one.

Divide students into small teams of 4-5 students and explain they’ll be competing to complete tasks (including regular classroom tasks) and earn points by demonstrating the skills. In addition to awarding points, teachers explained how each group demonstrated the target skills. At the end of the game, teachers summarized the skills with examples from the groups and gave rewards.

This cycle is repeated several times over several days or weeks with teachers adjusting target skills, changing points, and implementing additional supports based on students’ performance in prior games.

Repeat as necessary.

Now, on to the more detailed breakdown.

Discussion

There are about 30 studies looking at CW-FIT that I could find on my own, but WWC only reviewed 19 and felt that only 8 met their standards for including in the review. This is, I think, part of the value we all receive from this service. It’s a lot of work for anyone to frequently conduct literature reviews and analyses of studies. Individual teachers probably will not do this work. School administrators probably will not do this work. Indeed, schools seemingly believe salesmen who show up with “researched backed” studies for their product’s efficacy even if that research is sometimes badly flawed. It is a good thing to have people who are paid to locate and evaluate research and produce reports and practice bulletins to inform teachers.

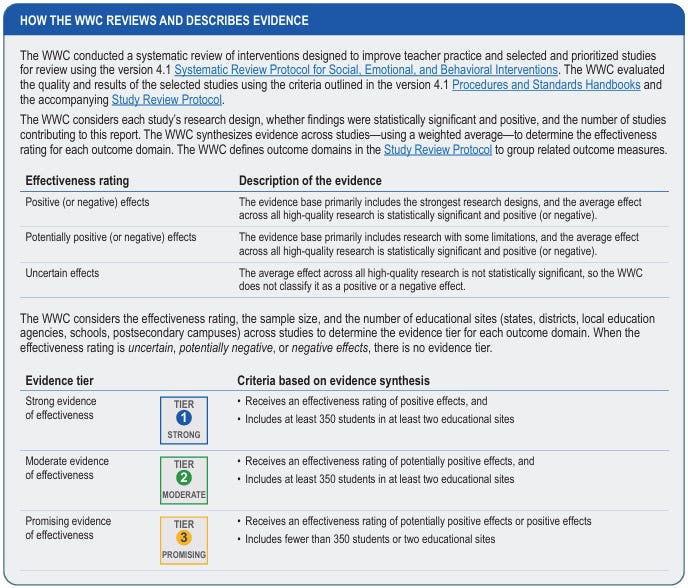

Within the eight studies meeting WWC’s standards, there some variation in setting between them. It’s been evaluated from elementary to high school and in both general education and inclusion environments. In general, the effects are positive with students’ behavior improving. The oldest study I could find was from 2016. That tracks as the institute at the University of Kansas where this approach originated only started promoting it through professional development a few years earlier. The DOE only counts some of those studies, however, and has its own process for determining the quality of the evidence. They explain it both in brief (below) and in detail and provide a summary of how they see the quality of the evidence for this practice. You can find links to the full report, a brief, and some appendices here.

source

source

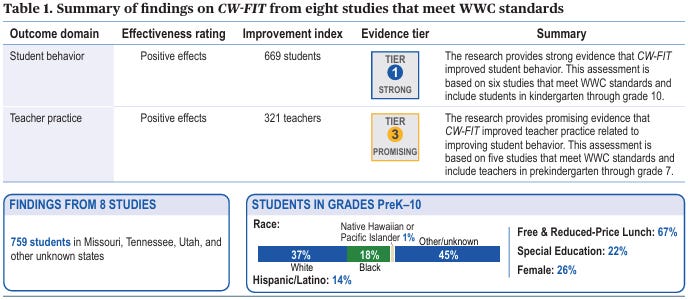

You can see that the WWC feels that there is strong evidence from studies they reviewed for CW-FIT improving student behavior. They assigned their lowest rating, “promising” for impacts on teacher practice. Reading a bit deeper into the full report and appendices, it looks like “promising” was assigned primarily because only five of the studies included an investigation into teachers’ practices and those five had smaller samples with lower effect sizes on teacher practice. They also did not include the three large high school studies so they only examined elementary and middle school teacher practices. I also had to dig into the study summaries to see what elements were considered teacher practice and that would be stuff like, did the study measure the frequency or quality of teacher praise? This is important because praise is a component of the intervention. All in all, I think they are accurately representing the research. (I did personally review skim all eight studies they included, accessible for free via ERIC!)

Questions

One thing I found myself wondering is which skills teachers wanted to target for intervention. It was kind of all over the place. Sometimes the “skills” were super broad like “showing respect” and other times they were more specific such as how to appropriately get a teacher’s attention. The reason for this is that interventions are tailored by the teachers to their classrooms. I know that is kind of unsatisfying because it’d be great to have a list of, like, 10 targetable behaviors for every classroom. That being said, I think the method is what’s meant to generalize, not the specific interventions. Indeed, this is probably why there are positive results in a variety of classrooms and at many age levels. Being able to tailor something to individual classrooms means it’s going to be highly applicable and responsive. We can all imagine that a few things probably do pop up regularly in any class: working collaboratively, not distracting classmates/ignoring distractions, sharing resources, staying on task, and so on.

I wanted more detail about the games themselves and dug into some of the studies to get a better sense of what some of these teachers did. In most cases, they use work from their daily curriculum as the game activity for each group of students and then observed and took notes as they worked for a set amount of time, say, 5-10 minute intervals. Then they’d stop, award points, and explain the positive behavior, include some praise, etc. Rewards at the end of the game took many forms from extended breaks/recess, to snacks, to more independent reading time. Teachers appeared to try and give everyone at least some kind of praise at some point in the series of games. The games themselves lasted between 30 and 60 minutes depending on the schedule of each school but there doesn’t appear to be a big difference in outcomes between the longer and shorter games. The frequency of playing the game ranged from once a week to once every 2-3 days. Usually, the frequency decreased after the 3rd or 4th session to about once a month or as needed if more skill work was required. CW-FIT does expect teachers to continue the intervention indefinitely as new behavioral challenges can arise, albeit at a reduced frequency.

In two studies, additional supports were prepared and deployed by the teachers after the first game. For example, one teacher created a printout of the class scorecard and gave it to several students so they could monitor and track their own behavior in the next game. In other instances, such as when kids wanted to avoid working, students were given a special card or flag to hold up to get the teacher’s attention and ask for help (getting the teacher’s attention was the target skill for that intervention, so this makes sense). And additional study reassigned students needing support to a new group then taught small group lessons those groups prior to playing the game again. Again, I want to highlight that teachers seem to be able to customize and modify CW-FIT while maintaining enough fidelity to the overall method and be successful. In my view, that makes this practice much easier to generalize because it is less rigid.

You can find free materials here. You have to make an account, but it’s with the academic institute so you don’t have too much to worry about. I won’t be reproducing them here due to copyright concerns, but I’ve made an account and looked through the materials. It’s pretty helpful stuff! The institute also offers coaching and staff development but that is not free.

Takeaways

If you step back and think about CW-FIT, it’s more or less just teaching. Look at the steps again: plan, explain, model, practice, assess, give feedback, debrief, repeat. We should want to do this with everything we teach but we don’t usually think about doing this with behavior. Underlying CW-FIT is the notion that classroom behaviors need to be explicitly taught and periodically re-taught in order to maintain the expected behaviors. The more I think about it, the more I like that CW-FIT doesn’t really specify what those behaviors ought to be which gives teachers the freedom to run their classes in their own unique ways. While the process is somewhat prescribed, it’s clear that there is room for lots of variability within the process. I’m encouraged that it seems effective with young and old students.

One aspect of CW-FIT appears a bit more prescriptive and that is their discussion of praise. When teachers give praise, CW-FIT wants them to do it as pedagogical praise. What that means is the praise includes a description of the positive behavior for the whole class as well as some explanation as to why it is helpful. Saying “Good job, Billy, you raised your hand!” doesn’t do much for anyone other than Billy. In fact, even Billy may not be totally clear on why his hand raising was good, only that it makes the teacher happy. That’s not really learning so much as appeasement. Pedagogical praise would pause the whole class (that’s why CW-FIT does it between game sessions so everyone is able to pay attention), explain that Billy earned a point (not that you are giving it, he earned it), and then explain exactly what Billy did in detail (Billy raised his hand and then watched me until he was sure I noticed him because he made eye contact, then he waited for me to come over and check with him/call on him/whatever). Finally, you explain why what Billy did is good for both Billy and for the class (Billy gets clarification/a bathroom break/hands in an assignment, the class is not interrupted or distracted by him shouting out). Pedagogical praise is something the coaching and professional development probably emphasizes and, like the previous paragraph, is kinda just good teaching. Being explicit is underrated!

A final thing to note is that CW-FIT is an intervention. It is meant to be implemented if a class is having trouble with behavior and has been studied that way. My question is, why wait? Why not use the time at the beginning of the school year to set expectations and use the process of CW-FIT to help students learn how to behave early on? One possible answer is that CW-FIT is time consuming. Teachers’ days are packed and pulling 30 minutes to 1 hour for several days from regular class stuff to do behavior management interventions is a big ask, especially if a class is not particularly problematic. Perhaps only one or two students need an intervention so a whole class activity is unnecessary. Still, I don’t see a problem with someone adapting CW-FIT to work with their start-of-the-year norm setting because the pedagogical principles seem sound and a stitch in time saves nine, as they say.

Goodbye ERIC and WWC

As a teacher of teachers, the next time I’m teaching a class that covers behavioral management, CW-FIT will make an appearance. The thing is, I would never have known about it if I had not spent time looking through the WWC for practices with highly rated evidence. Moreover, because WWC and ERIC work somewhat in concert with each other, all of the studies included for review are also made available for anyone who wants them. Since I read a lot of research, that’s fine by me and I am generally fluent enough in academic papers to read them and understand what’s going on. Thing is, you don’t have to go that far! WWC offers summaries and briefs that help you get to the meat of the practice without needing to bury yourself in the literature. And yet, with the funding to the DoE cut and many employees fired, it seems like both ERIC and the WWC will run out of money today, April 23rd. This means no new documents will be added to ERIC as new research becomes available. This means the WWC will have nothing new to review and will no longer provide new practice bulletins. Indeed, it’s also possible that the 3rd parties hosting the webpages and the documents will not be paid, and the services may go down entirely at some point. Teachers and schools everywhere, even private schools and charter schools and homeschoolers, are losing a valuable resource. Let’s hope it’s not forever.

Thanks for reading!