- Scholastic Alchemy

- Posts

- Giftedness is not what you think

Giftedness is not what you think

You're really talking about a separate track for kids who are good at school so ask for that instead

Welcome to Scholastic Alchemy! I’m James and I write mostly about education. I find it fascinating and at the same time maddening. Scholastic Alchemy is my attempt to make sense of and explain the perpetual oddities around education, as well as to share my thoughts on related topics. On Wednesdays I post a long-ish dive into a topic of my choosing. On Fridays I post some links I’ve encountered that week and some commentary about what I’m sharing. Scholastic Alchemy will remain free for the foreseeable future but if you like my work and want to support me, please consider a paid subscription. If you have objections to Substack as a platform, I maintain a parallel version using BeeHiiv and you can subscribe there.

Gifted is just a synonym for smart, right?

After seeing the rants and raves following NYC Mayoral candidate Zorhan Mamdani’s statement that he would seek to end NYC’s gifted and talented testing program for 4-year-olds, I decided to spend a little time digging into research literature about giftedness and gifted education. I was actually a bit surprised at how little I knew about giftedness, though maybe I should not have been because it’s not an area I’ve spent much time researching or learning about formally. I never attended gifted classes as a student (in part because my parents misunderstood gifted programs as a euphemism for sped, causing my dad to tell the principal, “my son is not retarded” and refuse to allow me to be evaluated. What a wonderful thing to experience as an eleven-year-old. Not being in gifted classes meant I was not considered for honors classes or for advanced placement classes. So, in my mind, gifted education was always about selecting out “smart” academically successful kids and putting them on a pathway to advanced courses. It was, more or less, tracking.

It turns out, that seems to be how the general public understands gifted programs, too. They generally think being gifted is about being the highest achieving academically and that programs are designed to give kids more rigorous and advanced coursework than their non-gifted peers. You can see this clearly in responses on that NYT article. Some of the top performing comments are those treating gifted programs as advanced coursework for high-achieving students.

If the top commenter is to be believed, gifted and talented programs are so important to the average parent that making programmatic changes such as identifying kids in 3rd grade instead of the year before kindergarten will have implications for the upcoming midterm elections! But, let’s look to these comments to get a sense of how people are thinking about what gifted programs do and who gifted kids are. Gifted programs are “accelerated” and are not “equitable.” Gifted programs are about “meritocracy” not “mediocrity” and lead “right into high school AP classes.” Gifted kids are, apparently, the kinds of kids who are precocious readers that “needs the challenge” and would “get bored at a slower pace.” Taking away NYC’s gifted test for 4-year-olds is equated with taking away “magnet/advanced placement programs” where we “encourage students to be the brightest they can be.” This perception of giftedness and gifted programs largely meshes with my own experiences and assumptions. And, it turns out, we are all pretty much entirely wrong. Gifted education as recommended by researchers who study giftedness, has little to do with providing the most advanced or most rigorous coursework for the most academically successful students.

Refusing to follow the science

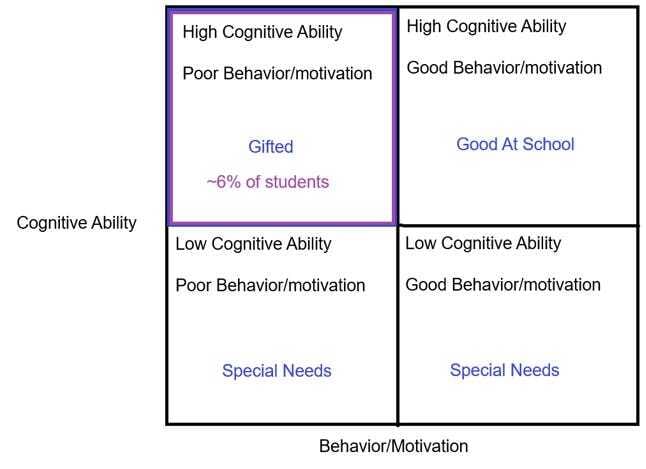

The big point here is that how we view giftedness is somewhat incompatible with how cognitive scientists and psychologists view giftedness. Depending on which view you’re working with, the scientific view drawn from research or the popular view drawn from parental expectations and desires, you will want different things from the gifted and talented programming in public schools. I decided to make a super rough and simple chart to explain who, based on my reading of the research, is gifted.

Not represented: the ~70-80% of average kids who weren’t going to pass the NYC gifted test anyway.

The quickest version of the remainder of this post is that research says only the small percentage of kids in the top left quadrant are gifted while the top right quadrant of academically successful students are just that, academically successful students. They’re good at school. Gifted students, on the other hand, are generally bad at school and need interventions in order to be successful in school, often interventions related to mitigating their poor behaviors and helping them build up the desire to actually do any work they’re not intrinsically interested in doing. What gets really interesting is that gifted kids don’t necessarily need or receive a more accelerated curriculum or encounter more challenging work. Gifted programs, if they are built to support the small number of actual gifted students as opposed to kids who are already good at school, often move slower and cover fewer things, choosing instead to go deeper. Gifted programs are often more project based and inquiry oriented than either the traditional curriculum or advanced courses. Now, it may be true that a gifted kid will excel in a particular area of interest and outperform most other peers in that area, but many times this is in a creative, non-academic area. One of the challenges discussed in the literature is just how many gifted kids are not being identified because so many states and districts only evaluate for academic success (which, again, most researchers will tell you is not what makes someone gifted). I think one of the best expressions of how variable our systems of enrolling kids in gifted programs can be is simply breaking down enrollment by state.

You mean to tell me that in 2018 10% of children in Georgia, 13% in Kentucky, and 18% in Maryland were gifted but that only 2% of kids in Tennessee, 2% in West Virgina, 7% in Colorado were gifted? Is giftedness distributed in the population of children such that crossing the border from Tennessee to Georgia suddenly yields 8% more gifted kids in the population? Mississippi has more than six times the number of gifted kids, proportionally, than New Hampshire. This must be the reason for the Mississippi Miracle! They just have more gifted kids! I think you get my point. It seems ridiculous to have this level of variation of giftedness from one state to the next and it indicates that the ways in which states identify giftedness are all over the map and, probably, unrelated to scientific understandings of giftedness.

This is your brain on gifts

A good place to start is with biology. To quote one review of the research, “there substantive evidence that gifted individuals have atypical brains and atypical brain functioning.” A more recent review notes,

Contrary to motor performance [which was poor in “high potential” kids when compared with neurotypical controls], executive function performance and development in high potential individuals have also been greatly studied, considered a possible contributor to their superior performance in information processing and cognitive regulation. Authors have argued that high performance at executive function contribute to academic success which has in turn fueled massive research on the topic (Brock et al., 2009; McClelland & Cameron, 2019). Categorized into three high order cognitive group of skills (Diamond, 2013), namely, Working Memory—involved in the recovery and processing of previous acquired knowledge, Inhibitory Control—including both cognitive and behavioral inhibition, and lastly Cognitive Flexibility comprising the ability to evaluate, select and adapt multiple cognitive strategies to achieve a purpose, executive functions have been showed to develop prematurely in gifted individuals (Bildiren, 2018; Vaivre-Douret, 2011). Johnson et al. (2003) found high IQ children aged between six and eleven to score higher on mental-attentional tasks and significantly demonstrated higher effortful inhibition capacity during interference loaded tasks. In their meta-analysis of 17 articles comparing executive functions in gifted versus non-gifted Rodrıguez-Naveiras et al. (2019) supported the verbal and visual working memory superiority hypothesis in the high potential group.

Just to note on my end: that review uses intelligence, high-potential, and giftedness as synonyms in part because it’s reviewing articles across a few disciplines where different terms are most common. Anyway, what we see in both reviews is that giftedness manifests in the brain’s ability to direct attention, retain certain kinds of information in working memory (thus improving task performance), and some degree of ability to utilize multiple strategies to achieve a goal. These capacities develop earlier in gifted children and outstrip other capacities, such as motor skills or emotional development. I should also note, though, that “earlier” doesn’t necessarily mean ages 3-4. Many of these studies are of adolescents and pre-teens. That is, more or less, middle schoolers. One reason for this is simply that the brain architecture that differentiates gifted kids from neurotypical kids takes time to develop for everyone, even if it develops a few years sooner in the gifted population.

From this neurodevelopmental perspective, it does not make sense to be identifying, say, executive functioning in a four-year-old because basically zero four-year-olds have the level of brain development of a 12-year-old which is when adult-like executive functioning is considered to normally begin developing. When I sound like I’m a bit more on Mamdani’s side, this is why. There’s just no good evidence that giving a single test to a four-year-old is indicative of that kid being gifted. When psychologists and cognitive researchers have evaluated young kids, the results on these kinds of tests are inconsistent and change enough over time so as to make them questionable indicators when used at a young age (Lohman& Korb, 2006). I’m simply skeptical that this test is the best way to identify kids for the program and other researchers have, in the past, agreed.

“As a general rule, test scores become more accurate as students age with second- or third-grade being when they tend to stabilize,” said Scott Peters, an assistant professor of education at the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater, who studies gifted education. “It was ridiculous to ID students at age four for any kind of long-term services.”

Now, that’s a bit different from the equity concerns that Mamdani cited and my only comment in that regard is to agree that if you have limited resources, devoting them to programs that affect the overall student population is probably more advisable than devoting them to a program that is seemingly improperly run via a single test that doesn’t seem to be supported by the evidence. What psychologists would prefer is that

Gifted assessment should be a recurring phenomena, not a one-shot event; some students not identified as gifted at an early age later develop the gifts and talents to make major contributions in innumerable fields, and some young students identified at an early age as gifted, for any number of reasons, fall off of a trajectory of academic excellence

The thing is, none of this means getting rid of gifted programs and Mamdani has not proposed getting rid of gifted programs, just stopping the test for four-year-olds and focusing on identification and enrollment starting in third grade.

Gifted programs won’t make your kid a high achiever

Another disconnect between the reality of gifted programs and the public’s perception is the sense kids in gifted programs do well academically. They don’t! Researchers have found repeatedly that the impact of gifted and talented programs on students’ academic achievement is minimal when compared with peers. Instead, it helps the gifted kids achieve similar performance to their non-gifted peers. This is true when examined longitudinally, too. And studies keep finding these kinds of results.

We provide evidence on whether the typical gifted program indeed benefits elementary students’ achievement and nonachievement outcomes, using nationally representative data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, 2010–2011 kindergarten cohort. Leveraging within-school and within-student comparisons, we find that participating in a school’s gifted program is associated with reading and mathematics achievement for the average student, although associations are small. We find no evidence of a relationship between gifted participation and student absences, reported engagement with school, or student mobility.

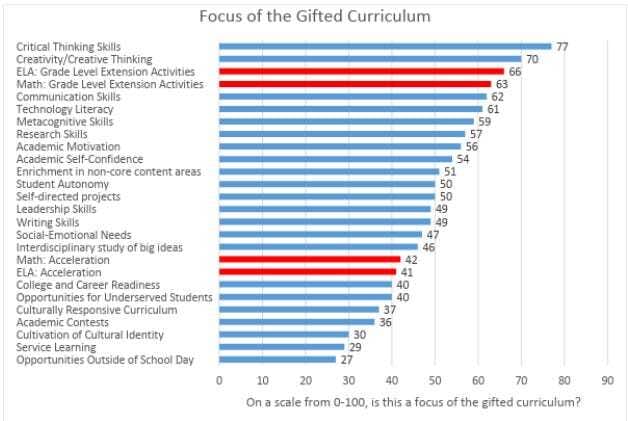

We know from surveys that gifted programs focus primarily on “enrichment activities” and non-cognitive skills and provide grade-level course content.

The thing is, this is only surprising and shocking for those who labor under the illusion that gifted education is about taking advanced kids and giving them a more rigorous, advanced curriculum. What we should recognize is that gifted education is about taking bright kids who underperform in school and bringing them up to an average level of performance in most subjects. Part of doing that is teaching these kids “how to do school” and working on their desire to do anything at all beyond the one or two things they’re interested in and good at. Look at what the survey results above show us: Critical thinking, creativity, communication skills, metacognitive skills (thinking about thinking), research skills, academic motivation and self-confidence, etc. Once you jettison the idea that gifted education is about advanced coursework, it becomes pretty clear that this is basically some kind of academic recovery program for kids who should be good at school but aren’t. If you want advanced coursework for academically successful kids, then make a program to do that.

Your kid probably isn’t gifted anyway

I think the low incidence of giftedness is one of the other key factors that doesn’t penetrate the public discourse. In New York, 1.6% of students were enrolled in gifted and talented programs in the 2018 school year (I don’t have more recent data, sorry). In New York City last year, 4% of 4-year-olds scored high enough to enter gifted kindergarten. All these worries that droves of middle-class parents will flee the city or send their kids to private schools or that valuable opportunities are being denied the working class simply don’t match the statistical unlikelihood that their kids will be enrolled in gifted programs.

Even in the studies in the reviews above, the incidence of giftedness is about 6-7%. The only time we get double digit numbers of gifted kids is when states have very expansive definitions or just automatically enroll the top 10% of students. Again, what’s happening is that parents are conflating giftedness with kids who are just plain successful in school. They don’t grasp, sometimes, that their kids are not even enrolled in gifted programs but are, instead, on an advanced academic track (or, perhaps, the gifted program they’re aware of is merely an advanced academic track and does no gifted education at all). And, of course, we have people conflating making a programmatic change with ending the program all together. This should tell us that people are not worked up about the gifted program at all but are instead worried about tracks and pathways for academically high-achieving students. Lots of middle class and working-class parents will have kids who can reach a high level of academic achievement. Very few have children who are gifted. Even fewer than that will, under the current NYC testing regime or whatever Mamdani chooses to do, have children enrolled in the gifted program. Harvard’s acceptance rate is 3.5%. It’s easier to get a kid into Harvard than into gifted programs in New York. So why do we act like this tiny program is somehow the lifeline keeping middle class and working-class parents engaged in public schools?

Just talk about the thing you want to talk about

New York City has eight highly selective public exam schools that are widely regarded as some of the best in the nation but are also incredibly exclusive. Admissions to these schools is controlled by the SHSAT, a standardized exam the city creates and administers annually. Mamdani, himself a graduate of one of these exam schools, has said he plans to keep the selective admissions and the exam. It seems clear from the reporting that Mamdani is not adopting some kind of anti-testing or anti-academic stance where he wants to end advanced coursework. I’m not sure how ending the test for pre-kindergartener children is the same as eliminating the gifted program altogether or is an end to separate programs like magnet schools or advanced placement courses. Suggesting so seems, more likely, to be the product of a caricature of Democrats as anti-excellence and an insistence that liberals and the left are somehow engaging in social engineering to create an equitable mediocrity. This kind of thinking around education is, sadly, par for the course and something I’ve written about a few times before. In general, the ones working to weaken the quality of the schools are conservatives. They’re the most opposed to testing and standardization. They’re the ones engineering school choice and vouchers along religious and ideological lines. But for whatever reason, we have to put liberals and democrats in their place with schooling.

There is, perhaps, a kind of metonymy problem at work, too. A city like San Francisco changes the algebra pathway for its middle schools, sees bad results, and has to reverse course. Somehow this is a failure for anyone left of center nationally and democrats are somehow the party that wants to sacrifice top students in the name of equity. Never mind that it was democrats who both implemented and repealed the policy! Nobody gets credit for fixing a mistake, I guess. And do it goes with NYC’s schools. Mamdani isn’t even mayor yet and he’s already causing democrats to take nationwide election losses because, I guess, making a change to gifted testing so that it better aligns with the evidence on when to best begin identifying kids for gifted programs, is simply a signal that democrats are once again going to destroy children’s futures. What one local NYC politician does has to be owned by the entire Democratic party, apparently. Whatever one part does must be attributed to the functioning of the whole.

Let me propose an alternative. If you want to talk about advanced pathways and coursework for students who are academic high-achievers, then just do that. Don’t talk about something completely different like gifted education. Schools all over the country offer advanced courses separately from their gifted and talented programs. Why not talk about those models and how they could be implemented in NYC? Talk about the thing you want to talk about and skip the euphemisms, signaling, and second-hand references. And, for the love of god, please stop making crap up about how Mamdani is going to end magnet schools or do away with all testing. If that becomes his policy, fine, let’s get mad about it but at least let him propose it first.

Thanks for reading!