- Scholastic Alchemy

- Posts

- How did we get here: 21st century skills

How did we get here: 21st century skills

Why are we doing Human Capital wrong?

First, some housekeeping. Welcome to Scholastic Alchemy, a newsletter/blog thing I plan to write weekly and publish on Fridays. My goal is to explain a bit about how schools work and why our endless good intentions seem to regularly run aground, going nowhere, as well as to share a handful of interesting education links. This first series of posts is called “How did we get here?” and the goal is to give an overview of recent trends in education that brought us to the very interesting inflection point we now inhabit. Last week I wrote about Phones in Schools and how their presence in schools is the result of a desire for students to learn the skills needed to succeed in the 21st century. Today we look at where that idea comes from and why it is so influential. If you enjoy the post, please subscribe. All posts will be available for free until March at which point the paywall will go up. A non-Substack subscription option will also be available.

It’s the economy, stupid.

One of the jobs we’ve given our education system is to prepare the next generation of workers by having them learn the necessary skills and gain the necessary knowledge that their employers will expect them to have. If that seems like an incredibly obvious statement, then I encourage you to think about why it might seem so obvious. I’d argue it is so obvious that many people have difficulty describing another purpose for education. Nowadays it is simply common sense to expect that education is some kind of training for work. Indeed, when people work hard and pay a lot of money for an education and then don’t get good jobs, they’re upset. Why is this common sense? Why is this the conventional wisdom? Why is it obvious to you and I that this is what school is for? I believe the main reason this view of schools has succeeded is because Human Capital Theory, from the world of economics, is the main way lawmakers, policymakers, and even the general public think about education.

I should note at this point that I am not going to argue this view of schooling’s purpose is wrong. The point of the How did we get here? series is to be descriptive. It’s about the state of play right now and how I beleive our system of education arrived at this point. Do I think schooling has purposes beyond job preparation? Absolutely! One thing the pandemic made clear is that schools are, if nothing esle, a place to warehouse children so their parents can work (hey, look, another economic imperative). One of the most fascinating things about the conservative rebellion sweeping school systems is that conservatives seem far more able to articulate different ideas about what school is all about. For example, it might be to instill western values, a sense of patriotism, or encourage civic-mindedness among the populace. Perhaps schools are a sorting mechanism whereby the best — whatever that may be — are given more resources and support with the expectation that they’ll have the biggest positive impact on society. These ideas and more are out there actively circulating and, I’d argue, will be influencuing education for many years to come. But that’s the topic of another post. Back to economics.

Remember your Becker

One reason I want to write about human capital theory is because I think it gets unfairly lumped in with criticisms of neoliberalism. Discussions of education need more nuance and the tendency to denounce anything you don’t like as neoliberal is no longer helpful. We’re almost at the point where the average internet denizen just uses neoliberal to mean bad. This is far too simplistic. I think, too, that critics of neoliberalism need to accept that neoliberalism started dying in 2016 and doesn’t seem likely to return to life anytime soon. To make this case, I want to quote something from the introduction to the second edition of Gary Becker’s 1964 book, Human Capital.

In the preface to the first edition written about a decade ago, I remarked that in the preceding few years “interest in the economics of education has mushroomed throughout the world.” The mushrooming has continued unabated; a bibliography on the economics of education prepared in 1957 would have contained less than 50 entries, whereas one issues in 1964 listed almost 450 entries and its second edition in 1970 listed over 1300 entries. Moreover, this bibliography excludes the economic literature on health, migration, and other nonschooling investments in human capital, which has expanded even faster.

Two things interest me here. First, note the timeframe he’s discussing. 1954-1970. Pretty much everyone I’ve read would point to the 1970s or 1980s as the start of the neoliberal era. Most of the data Becker used when initially developing Human Capital Theory is from 1900-1940. A recent Nobel laureate in economics, Claudia Goldin, cut her teeth, doing human capital research around the advent of mandatory public high school in the 1920s and 30s. This is hardly the heyday of neoliberalism. Goldin followed this up with analyses of women’s entrance into the wider workforce in the 1970s and onward. Becker, in his Nobel Acceptance speech points out that human capital research was used to argue against segregation, apartheid, and discrimination against minorities in the workplace. Critics of neoliberalism, especially in education, often argue that neoliberalism led to more discrimination and segregation, so it seems incorrect to lump human capital in with the neoliberal era.

This brings me to the second point. In the quote above he lists nonschooling human capital such as health and migration. While he may find agreement with neoliberal views on migration, Becker was agnostic on immigration for most of his career and preferred to examine why people moved and how they gained more from a skillset in some places more than others which led to clusters of similarly skilled people in one area. This, by the way, is one of the roots of another Nobel laureate’s work on economic geography, Paul Krugman — hardly a neoliberal shill. With regards to health, Becker showed that improvements in both public health and in healthcare were investments in human capital, too. I think that if you went to a policymaker today and asked, “how can we invest in human capital?” they would only think of schools and job training. We’ve forgotten that Becker’s Human Capital Theory was, in fact, more about the nonschooling aspects of human capital that he says, “expanded even faster”. If anything, I think a case could be made that neoliberalism’s push against public investment featured a great forgetting of many of Becker’s lessons.

Let’s bring this back to education. Becker’s big insight is deceptively simple. We invest in education in order to have a better society as measured by 1) growing labor productivity and, therefore, the economy; 2) increasing workers’ incomes. Prior to Becker, the economic idea was one of “labor power” in which every worker was roughly the same as any other and what they produced was largely static. As I understand it, schooling was seen as largely unimportant beyond a certain point, and they felt that only the training for a job led to a single stable one-time increase in productivity. e.g. you’d learn how to use a machine in the factory when you arrived at work, and they trained you on that machine. After that, you were more productive because you had the specific skills and knowledge to use that machine. School didn’t really play a role here. Becker showed that the opposite was true. He distinguished between general skills and knowledge learned in school and university and the specific training provided skills and knowledge provided by the workplace. General knowledge and skill from schooling had a much larger effect on productivity that grew over time. Precisely because these skills were generalizable, train and retrain, become more productive in a single role or move to a new role that enabled more productivity, and so on. (This is probably more of the Nelson-Phelps view of it — human capital as the ability to be flexible and adapt — but I don’t see why they’re incompatible.) Schooling yielded higher productivity, growing productivity, and higher incomes for workers. This, Becker says, is the essence of human capital. It’s investing in people so they can pursue opportunities. If you’re like me and remember the last 20+ years of focus on skills for the workplace, you might be wondering “what happened?”

Misunderstanding Theory

I noted earlier that people, especially politicians and policy makers, seem to have forgotten about all those nonschooling aspects of human capital. Another forgetting seems to be around the general/specialized skills distinction and how schools should prepare students for the future. We can see a good example of this right now with the increasingly vocal push to integrate AI into all aspects of schooling. Much of what we see are arguments that students need to learn to become AI prompt engineers. We’re told by boosters that learning to be AI prompt engineers is necessary because it’s the future of work and provides key skills needed to succeed.

moonprenuer.com throwing out buzzwords like there’s no tomorrow

Becker would, I think, argue the opposite. It would only make you a more productive AI prompt engineer. The specific skill of AI prompt engineering will not yield the skills of “advanced literacy and writing, critical thinking, quantitative analysis, and statistical skills.” Instead, he’d probably expect that schools would provide the latter so that a sufficiently literate critical thinker with quantitative analysis and statistical skills — general skills — would make a good AI prompt engineer or any number of other jobs. I need to admit, though, that this reaction is partly speculative because Becker never spent time measuring skills and knowledge from schooling. His research, and others in his tradition, was entirely based on outcomes. If workers’ productivity and income went up, that was a return on their education whatever it may have been. Much of Becker’s data was already almost half a century old when he started developing Human Capital Theory. Whatever schools were doing in 1903 is probably very different from what schools were doing in the 1960s and 70s when Becker was publishing the bulk of his work. This is, I think a strength and a weakness. It’s a strength because subsequent analyses of the returns on schooling in more recent decades support his findings. We can be confident that, on average, schooling does indeed make people more productive and increase their income. It’s a weakness because his research doesn’t tell us what schools should be doing specifically to get these results.

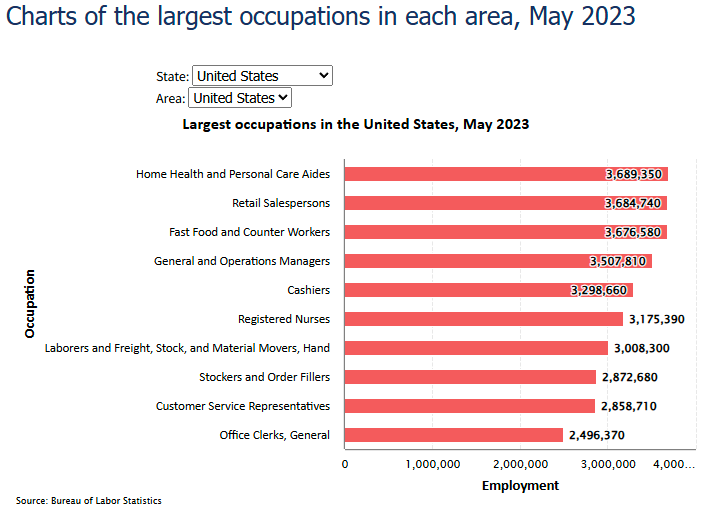

And that’s where, for those of us on the school side of things, the problems begin. When we acknowledge that schooling is broadly good, grows the economy, makes us more productive, and makes us wealthier, then it becomes something policymakers want to pursue and invest in. It becomes something parents and their kids want to pursue. It becomes commonsense to say that more school is better because you get more skills. However, since we don’t know what the general skills are that produce these gains, we traditionally turn to two places to guide us: employers and universities. And now we get to the 21st century skills stuff. There is a cottage industry dedicated to producing 1) data about which jobs we will need in the future, and 2) what the requirements of those jobs are. There is a case to be made that these prospective employment statistics are not on the up-and-up, but I don’t think that’s the core of the problem here. Every industry produces reams of data in order to make better informed decisions about the future. That the world of education is beset by custom proprietary statistics about the job market should not be a surprise since the commonsense view of education is one of career preparation. What I find interesting is that these data disagree with what the Bureau of Labor Statistics says actually happened. If you look at the BLS data, it shows us the largest occupations across the various job types they track.

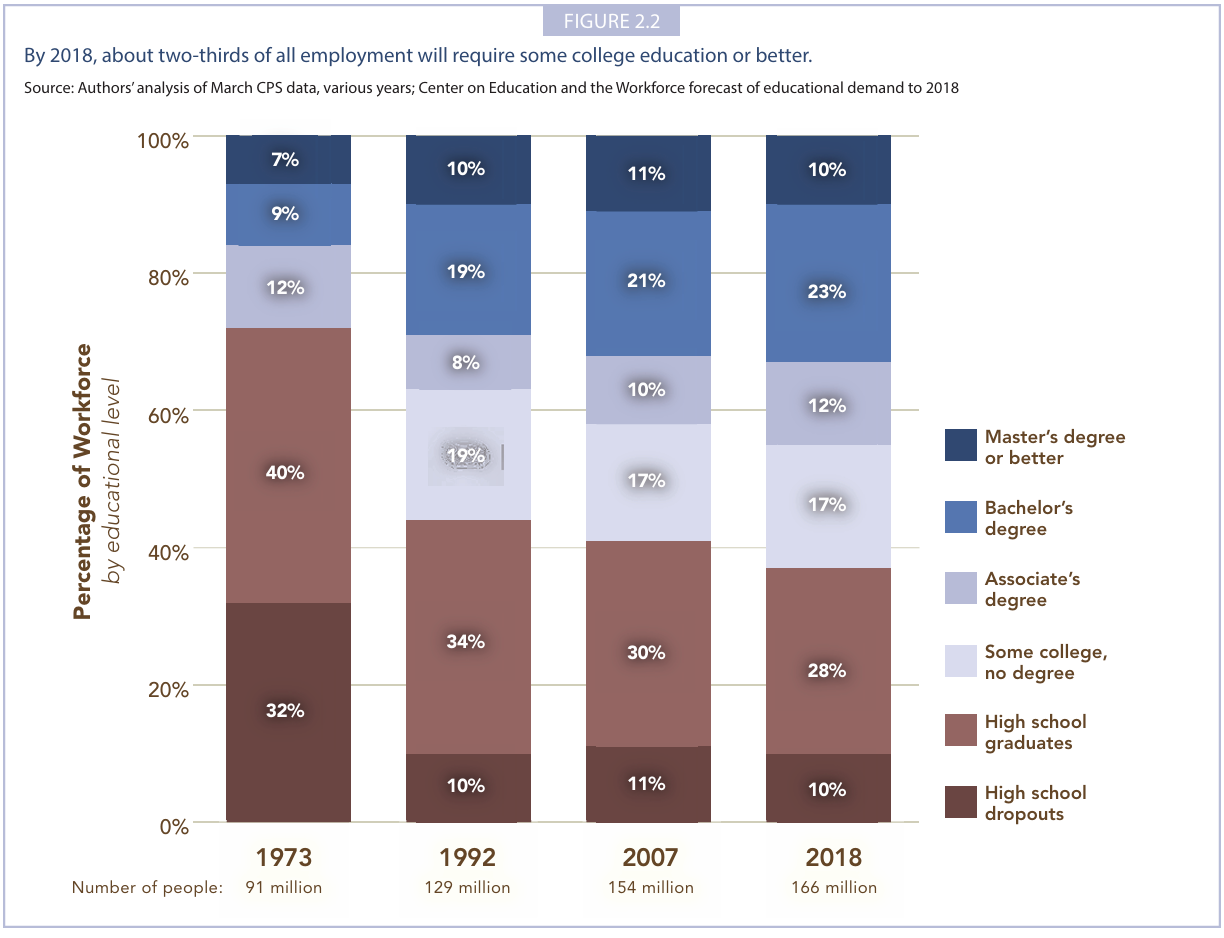

Most of these are not considered high skill jobs and only nursing requires a college degree (or more). However, when you look back at predictions of how many jobs would require college degrees, they are wildly different. For example, the Center for Education and the Workforce, a think-tank housed at Georgetown University and funded by a variety of philanthropies, published a report in 2010 projecting that by 2018 “about two-thirds of all employment will require some college education or better” (p.14).

Unless this happened in 2018 and then reverted by the time the BLS published its data in 2023, I am pretty sure ~60% of all employment did not and does not require at least some college. Infact, some reviews of historical BLS data argue that the share of jobs requiring a college degree has remained between 30-40% since the 1970s (Kraus, 2023). I may be picking on the CEW here but similar claims about the importance of sending as many people to college as we can dominated the conversation until very recently. In turn, schools reorganized themselves around pushing more kids into college even though most jobs would not require that much education. This meant sidelining vocational pathways in favor of college preparatory coursework for all. It meant, drawing on examples from my own research, that schools would rename the counselors office or the guidance office to College and Career Readiness Center.

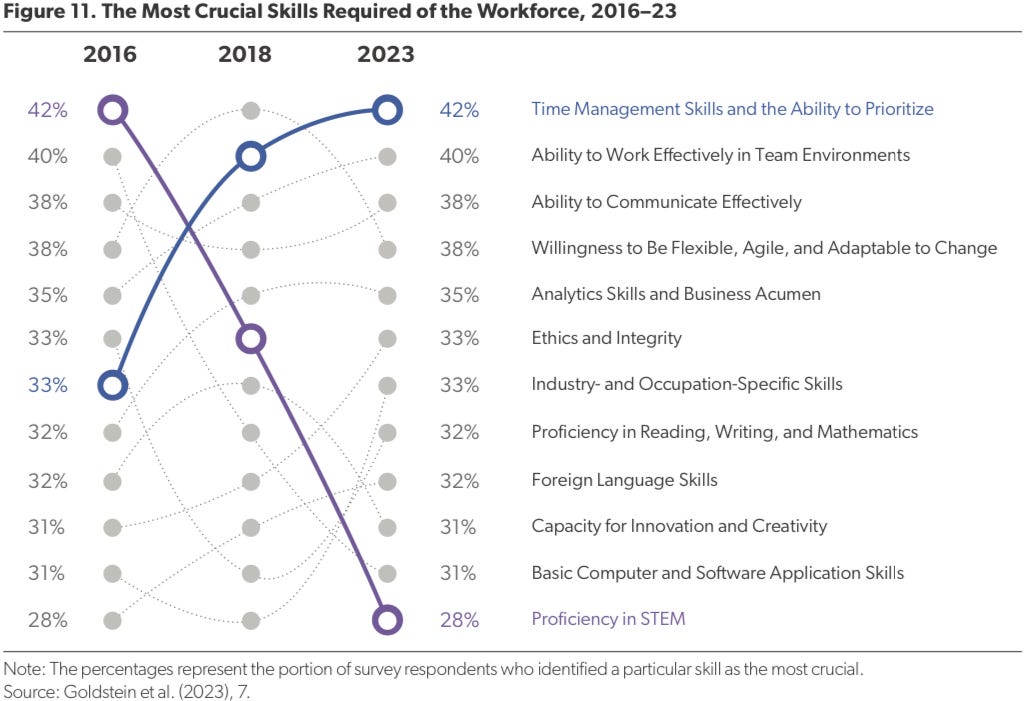

Employers, meanwhile, seem to change their desired skills fairly often. Often enough that it would seem like we need to completely retool the education system every few years. I came across a great example recently drawing on a 2023 survey of employers:

We all remember the big push for more STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) in schools. It’s kind of still going on! And yet we moved from just over 2 in 5 employers saying STEM proficiency was a crucial skill to just under 1 in 3. Computer skills saw a similar decline. If you were in 6th grade in 2016 and your school system prioritized STEM (via incorporating cell phones into the curriculum), by the time you graduated in 2021 half as many employers cared about your STEM proficiency. If you were a sophomore in high school trying to go into a STEM field, by the time you graduated college in 2021 half as many employers cared about your STEM proficiency. Sorry, I guess you should have studied AI prompt engineering. Indeed, there have been doubts that the STEM curricula in schools bears little resemblance to the ever-changing demands of the STEM workplace. Freddie deBoer somewhat infamously panned this kind of endless chasing of employability by suggesting the most practical major was French.

Yes, French. The major that’s so often derided as the height of impractical folly, the interest of people who want to fritter their time away reciting poetry and watching New Wave cinema, in fact revolves around a skill that has a great chance to be invaluable in the coming half-century: the ability to communicate in one of the fastest-growing languages in the world. Though it’s barely discussed in American news and commentary, central and west Africa — that is to say, Francophone Africa — has seen a population explosion in recent decades that’s arguably the biggest in the world. And while birth-rate growth in the region has started to level off, declining birth rates or outright declining populations across the world mean that the French-speaking part of Africa will play a huge role in determining humanity’s future. The French language rises with it. To put things in relative terms, the Francophone world, where as many as 525 million people live, is larger than the entire European Union. And where population growth happens, economic importance tends to follow.

I do find it interesting that the skills these employers now say are important are the most general skills imaginable: time management, work in teams, communicate effectively, adaptability, etc. This would seem to be a point scored for Becker but maybe they’ll same something completely different in a few years? I do wonder if a similar poll today would see something like AI prompt engineering at the top. Then again, aren’t these generative AI systems already moving away from written prompts?

Scholastic Alchemy

The title of this newsletter/blog is adapted from the work of Thomas Popkewitz who is well known for, among other things, a paper called The Alchemy of School Subjects. The quick version is that the curriculum of subjects we see in classrooms, such as math and science, undergo changes from a variety of influences that lead to reforms having unintended and unexpected results. He calls this alchemy because while the intent may be to turn lead into gold, something else seemingly always happens. I would like to extend this idea beyond the classroom to our entire system of schooling. We’ve seen reform after reform fail to produce the expected outcomes. There are many ways that ideas drawn from politics, economics, various academic research traditions, the media, the public, and so on enter schools and change in unexpected ways. We have cultural idioms about this! No plan survives contact with the enemy (military saying). The best laid schemes o’ Mice an’ Men/Gang aft agley (Robert Burns, poet). Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth (Mike Tyson).

Scholastic Alchemy means unintended consequences, unexpected complications, but also serendipity and happy coincidence. It means the stated purposes of school may differ from the underlying ideologies and theories of action. It means that schools are messy places where society dumps its fears and hope for the future right alongside kids shaped by today’s digital culture and by our nation’s history. It’s hopeful adults encountering grinding standardization and somehow managing to make it work. There’s some degree of unknowability involved in schooling and rather than try and eliminate it, we should embrace the ambiguities and roll with the undulating ever-changing terrain. Moreover, we should see the ambiguity as opportunity to try new things and make changes to whatever we consider obvious or commonsense.

In writing about Human Capital Theory here, I have tried to give an example of how an important economic theory is transformed as it passes from the pages of economic literature, into policymakers and thinktanks, and then as pressure on schools to keep up with changes to the job market. Along the way, the central insight of human capital is stripped down and altered. We forget that human capital includes many nonschooling components. We forget to distinguish between general and specific skills and expect schools to do both. We turn from the reality of the job market to projections that, seemingly, never come true. By the time you’re a kid in a classroom or a teacher or administrator trying to meet these demands, the goalposts seem to keep moving as new and different jobs appear and disappear. Digital literacy seems like a key 21st century skill but then the kinds of things we count as digitally literate in 2015 are less helpful by 2025. Along the way we threw tech into classrooms because incorporating more tech was supposed to help digital literacy and because that’s what the workplace of the future will look like. Instead, it has eroded kids’ and teachers’ focus and drive. It turns out that probably what leads to digital literacy is just having a high level of bog-standard literacy. This is the essence of Scholastic Alchemy.

Links

*NOTE: not always about education

This article in The Chronicle of Higher Education should be required reading for anyone who even says the word school. It’s an overview of education reforms under the Obama administration but has the interesting angle of investigating whether school reform policies are the reason we have a generation of college kids who hate learning, can’t read anything longer than a few hundred words, and possess little aptitude for focus and attention. This is, of course, highly relevant to what I’ve been starting to write about here. Scholastic Alchemy!

You may remember last week’s links features a pair of stories about AI in schools, including a school that claimed kids could do all their schoolwork in a few hours via AI and spend the rest of the day on SEL or whatever. Dan Meyer follows up on the same school run by the same CEO just got approved as a fully virtual charter school in Arizona. There it’s called Unbound Academy. A taste from his conclusion:

Educating everybody, especially under those worsening conditions, is a task that requires a significant number of humans—teachers in particular. If you tell me your school doesn’t need teachers, my first guess is either that you are misleading me or you aren’t trying to educate everybody.

This is the case with Unbound Academy, which is hiring just as many teachers as the public schools it derides in its charter application. This is the case with the Alpha private school network, which gets great results, as far as I can tell, not by replacing teachers with AI, but by replacing poor kids with rich kids, by replacing unengaged families with engaged families.

I’m someone who would love to live in a world of utopian abundance brought on a combination of robotics and AI achieving something like general intelligence. I do not consider myself an AI skeptic. Instead, I am a skeptic of people and their desire to sell us snake oil cures for all that ails us. Doubly so in school. Benjamin Riley draws an interesting comparison between Enron and OpenAI. Enron, if you’re too young to remember, was a company that perpetrated horrible financial fraud that continues to mess with Texas’ energy grid to this day.

Seems like PowerSchool got pwnd by ransomware. They provide data services to something like three quarters of school districts in the US. It’s not clear if a bunch of student and parent and school employee data was stolen. Many districts backend computer systems are broken at the moment, making everything from grades to attendance to payroll take forever to process. Funny to think that a super decentralized education system like ours is still centralized in so many ways.

The wildfires continue in and around Los Angeles. I’m drafting a post related to this that points out our failure to prepare schools for these disasters. I am reminded by these fires that a prior bout of wildfires in California left kids out of school for months. These kinds of disruptions to education are only going to grow in as climate change increase the frequency and severity of natural disasters.