- Scholastic Alchemy

- Posts

- How did we get here: Breaking the charter school treaty (Part 1)

How did we get here: Breaking the charter school treaty (Part 1)

An informal agreement helps explain limited changes but it's not the whole story

First, some housekeeping. Welcome to Scholastic Alchemy, a weekly newsletter where I write about education and share a handful of interesting links. My goal, at least right now, is to write about how the US arrived at the current moment in education, a moment where it seems like everything we know and trust about schools is about to go out the window. If you’re interested in this kind of thing, please subscribe. I plan to put up the paywall in early March. If you do not like Substack as a platform, I will be publishing a parallel version using Beehiiv.

Whence neoliberalism?

For the last three weeks I’ve been focusing on a particular economic idea, Human Capital Theory, and how it has been somewhat wrongly interpreted to mean schools should be focused on training for specific jobs, especially jobs that are (incorrectly) expected to dominate the future labor market because of technological change. One of the points I’ve been keen to make is that human capital is not part and parcel of neoliberalism. While neoliberals are happy to adopt portions of this economic theory, it preexists the neoliberal turn and has many features that do not mesh with things critics claim neoliberalism is doing. That said, many of you may be wondering why, then, if this is the dominant economic idea influencing thinking about schools, have we seen reforms that seem primarily neoliberal in nature. Things like school choice, vouchers, standardization and accountability have, in the US, felt like changes that followed a vision of school that is, to borrow from scholar Bettina Love,

…that competition is good for the economy, that the free market will solve all of our financial and social problems, and that deregulation is best, regardless of how it impacts the environment or job safety.

The neoliberal agenda in terms of public education is decades old. School districts such as Chicago’s have been experiencing deep budget cuts, mass closures of neighborhood schools, and an increase in charter schools, creating competition for the city’s poorest neighborhood schools for, for years.

— We Want to Do More Than Survive, 2019, p.145

If you’ve spent any time around colleges of education, teachers’ unions, or left-leaning advocates for the last twenty years, what Dr. Love describes above is nearly gospel. Frankly, strikes me as an inadequate explanation and this pair of posts is my attempt to lay out why I think that. Mind you, I’m not picking a fight here. I think there is ample evidence of these things happening and of neoliberal style explanations for why they are necessary. What I instead want to offer is a glimpse further back into the past where the motivations on display were transparently racist and framed around religious evangelization. Neoliberals are, in my reading, useful idiots carrying water for reactionary conservatives playing a much longer game. Settle in for a long post because it’s going to take time to make my case. Part two will follow next week.

The Charter School “Treaty”

My thinking about education reform changed quite a bit in recent years and probably the single biggest influence on my thinking comes from the work of political scientist David Menefee-Libey. Menefee-Libey spent time studying school change in Minnesota, California, and Illinois and developed some ideas about how reforms can succeed or fail at the political level. As a byproduct of these studies, Menefee-Libey came to understand something about how education reform in the 90s and 2000s resulted from something of a compromise or bargain between conservatives and liberals during tail end of the Regan era.

Here’s some very broad history of US education. We have a highly federated system with a very limited role for the federal government and much of the policymaking power is held at state and local levels. Over time, the federal government has intervened in a few large-scale ways, often through rulings by the Supreme Court. Brown vs BOE led to two decades of court battles and federal civil rights actions in order to desegregate schools. Initially, some conservative states participated in “massive resistance” to stimy efforts to integrate schools. At the same time, anti-integration thinkers began promoting alternative structures for American schooling, especially funding. Milton Friedman penned his famous essay The Role of Government in Education in 1955 and introduced the idea of school vouchers to a broader public. Vouchers and similar school choice schemes were seized upon by pro-segregation southerners as well as by conservative Christians as a way around integration (and secularization) efforts. Several states saw short-lived efforts along these lines, but most were effectively ended by federal courts. From the very start, school choice is an effort to undo the integration and secularization of American schooling.

By the end of the 1970s, most of this had been litigated and legislated into a system of busing and court or federal supervision to ensure schools did not resegregate. Indeed, even private schools were forbidden from discrimination by race (though the standing of individuals to sue private schools for their role in maintaining segregation of public schools was dealt a blow a few years later). School policy was often mired in disputes and complicated by lawsuits and reforms of any kind became difficult to implement due to strong opposition by the other side. As the 80s wore on, a détente or bargain was reached.

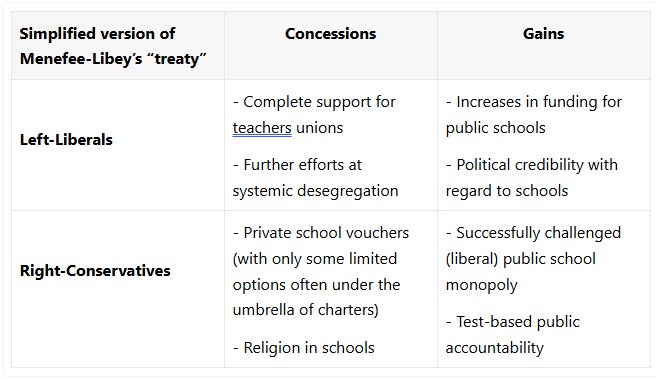

Menefee-Libey argues that the left stopped pushing for integration, settling for measures already in place (even tacitly accepting scaling them back, as eventually happened via the courts) as well as backing away from full support of teachers’ unions (who came to oppose non-union charter schools years later). Meanwhile, the right stopped pressing for prayer in school or government funding of religious education and stopped trying to fully privatize or voucherize school systems. Subsequent reforms would flow through things like curriculum (standards took off in the 80s and 90s), expanding charter schools (Minnesota and California were the first two states to allow charter schools in ‘89), or specialized vouchers limited in scope (e.g. the Wisconsin voucher system passed in 1989 which was a limited effort to get poor black kids in Milwaukee more options than their “poorly performing” urban schools). While these were meaningful changes, by and large the overall structure and funding of schools in the US remained the same.

Importantly, both sides also gained something. For example, Menefee-Libey was “in the room” as negotiations saw Democrats in California gain money and political credibility for public schools while Republicans there gained a system of charters where they felt conservatives could have influence (religious charters were excluded) and a system of public facing test-based school accountability for public schools.

Menefee-Libey characterizes charter schools as the key to this whole treaty whereby both conservatives and liberals could enact reforms, find schools whose values they shared, and generally leave the broader systems of public schooling untouched. When large-scale reforms did happen, like No Child Left Behind, it was at the federal level with bipartisan support and often played into the limits of the charter school “treaty” (e.g. more test-based accountability being a conservative goal, but vouchers and religious education were kept off the table by liberals). In many ways, this was a centrist move that paved the way for what we now see as a neoliberal era of school reform.

Menefee-Libey’s analysis helps explain why the only reforms we saw from the 1990s-2010s were those we’d now characterize as neoliberal: limited school choice via charters and test-based accountability. It also helps us see how those were not really priorities for either side. Instead, we have the reforms we do because neither side could get what they originally wanted. Looking back to the middle of the 20th century, we can see that conservatives wanted two things: segregated schools and state funding of religious schools. Over time, the “treaty” began to break down and those original right-wing priorities began to reassert themselves within the limited, neoliberal reforms. Next week I’ll outline how this multi-decade effort worked in Ohio.

Breaking the Treaty

Compromises, however, are never permanent. Menefee-Libey reminds us that treaties are the product of what each side is seeking and have to be interpreted as such. For the left-liberals, there was a sense that this treaty was “case-closed” and represented a much more permanent state of affairs whereas conservatives saw this as a steppingstone to more changes down the road. (Just like we see over and over in other aspects of our politics, conservatives are working with a long-term ideological position while liberals are more focused on processes, procedures, and imagine they are settling things: e.g. abortion!) Conservatives made the deal because they felt they were going to be driven out of the education space entirely. Democrats made the deal to pursue their reform agendas. Regardless, the treaty is now in tatters. Depending on how you interpret it, the treaty came apart under either Obama or Trump and the various sub-movements happening during their presidencies.

The way I usually look at it is that the Obama administration didn’t depart much from the Bush admin’s education polices. While they scaled back some of the NCLB accountability measures, Race to the Top used money as a big “carrot” to get schools to continue following those policies. Menefee-Libey points out two things here. The first is that the compromise was a political one so violation would have been in the political system rather than in schools themselves. The other is that there was another side to what the DOE was doing under Obama that riled conservatives leading them to open the door to more radical reformers like Betsy DeVos (Trump’s first secretary of education). What did the Obama administration do? They saw their work as multiple interlocking pieces working together to make large-scale improvements: common core, better assessments, teacher evaluations and value-added accountability. They implemented these in Race to the Top.

What they failed to anticipate is that the right felt like this move violated the treaty, especially their perception of the Common Core State Standards as a big government imposition. (Indeed, many people continue to see the Common Core as a federal initiative despite it being passed state by state.) When you started to see people object to the common core, it wasn’t primarily the liberal, diverse cities but the whiter, wealthy suburbs whose schools were “fine” and who disliked the changes to curriculum, additional testing, and what they saw as overreach by the feds. For example, in New York, the hotbed of the “opt out” movement where students and their parents refused state exams was suburban Long Island, not NYC. Menefee-Libey points out that the treaty’s unofficial framework stipulated NO BIG CHANGES and that it works both ways. While democrats at the time the treaty was drawn up were trying to stop full-on privatization, conservatives wanted an end to top-down integration initiatives they saw as meddling. Although NCLB and RTTT were also top-down initiatives, my experience in schools tells me it was really Common Core that came along and blew up that consensus. The American public really likes local control of their schools and will eventually turn against whatever they interpret as taking that control away. With wealthy white families outright resisting these changes, conservatives found a new audience for their old ideas.

The New Reform-al

Warranted or not, the Obama years signaled bad faith to conservatives who had no problem empowering more radical reformers when they came to power under Donald Trump. DeVos comes in in 2016 and sets the agenda for the post-treaty education landscape. The federal role needs to be minimal, encourage privatization via unlimited vouchers, and expand charter networks to include religious schools. Liberals were, to some extent, surprised. They looked back at the treaty and felt conservatives broke it by returning to their original plans. So, that’s the state of play we’re in today as Trump’s new administration re-takes over the Department of Education. Many states have now broad voucher systems where money follows kids, even if they go to religious schools. Lawsuits are attempting to get permission for public funding of religious schools. The post-Common Core curriculum landscape is also a mess, with battles over the content of school curricula being waged in school board meetings around the country.

My expectation is that the education reform in the last 20 or so years will seem tame by comparison to what could happen in the next 20 years. I’d argue we’ve already seen a big resurgence of localism from right-oriented groups in addition to right-leaning state legislatures passing various voucher laws and curriculum limits (Florida being the most famous example). It would be a mistake, however, to see this as a purely conservative phenomenon. Advocacy around the “Science of Reading,” for example, is changing elementary reading curricula primarily in blue states and cities (exceptions being Mississippi and Tennessee). Everyone was dissatisfied with pandemic-era school closures and there seems to be universal acknowledgement that this led to academic setbacks. Criticism of skills-based curriculum models (like the common core) argue we need to focus more on building deep knowledge than on demonstrating isolated skills. All of this sits on top of demographic trends (declining youth population, more diverse students) and technological trends (AI, labor vs knowledge work vs service work).

Next week, I want to continue this line of thinking by using the example of Ohio’s school voucher program. What started as a program for poor minority youth to escape “failing” urban public schools slowly expanded into a voucher program for all Ohioans. This expansion took place as part of a 30 project by a few key conservatives and their allies in the Catholic church, some evangelical groups, and business leaders. The Ohio model shows how Menefee-Libey’s treaty initially limited large scale change but also how revanchist conservatives understood and pursued an incremental approach to securing their ultimate goal, the public funding of religious schools.

Links

NOTE: Usually but not always links about education. Also, I’ll try to better demarcate one link from another by topic.

A new documentary is in the works called Class Wars, about how public education is being dismantled by a coalition of religious groups, conservative politicians, and business leaders. That sounds really familiar! There’s a teaser at the link but here’s another sampling:

<iframe title="vimeo-player" src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/818567202?h=99f917d3d4" width="640" height="360" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe>

The COVID-19 stuff is really fascinating. I know people who’ve lost family members, who lost co-workers, and specifically remember dropping my wife off at work next to a refrigerated corpse wagon then going home and teaching a course on elementary literacy online. I know lots of teachers who were really pulling out all the stops to try and reach their kids, teach well, all while managing their own personal struggles with the early pandemic lockdowns. We’re shoving all that in the memory hole because, online education is good now that Chat-GPT is doing it, I guess. I don’t know when the documentary comes out but will definitely be watching it.

University College London posted an article to their website about how much technology preschoolers in South Korea are using. Given our discussion of phones in schools and the seeming need for technology to help us keep up with scary Asian competitors, I found this section quite telling:

Recognising [sic] this tension, we recently conducted a UCL Global Engagement funded study to understand how early childhood practitioners in the UK and South Korea used technology within their classroom practice and viewed the use of technology in early childhood settings. Our headline finding was that 3–5-year-old children were exposed to a far wider pool of technology in South Korea in comparison with the UK. For example, while children in both contexts used tablets and iPads, children in South Korea were also regularly engaged in coding activities, and used robotics, virtual reality and green screens.

The implicit message here, of course, is that early childhood education in the UK is inadequate because children there are not exposed to a “wider pool” of technology. And, just as I pointed out, these researchers argue embedding technology is good and necessary because

we know that learning to read now includes developing skills to make sense of screen texts, and learning to write now includes learning to code using programming languages. This raises challenging questions for the field of early childhood education, particularly in relation to potential tensions between the desire to offer children opportunities to develop the digital literacy skills needed to succeed in the future and the desire for them to avoid the harmful effects of technology

Ah yes, human capital through specific skill training in what we assume will be the jobs of tomorrow. Just because I could, I looked up the current unemployment rates in the UK and South Korea. Although the UK’s is higher, both appear to be at or near historic lows. I’m sure that’s explainable through preschool technology adoption cycles.

If you’re interested in education technology and are not reading Audrey Waters, you should be. Yes, it’s another newsletter and you need to pay to read it but you should. Hell, don’t pay for mine. Pay for hers. Her book, Teaching Machines, is excellent. Much of what she writes about includes familiar themes:

The shift of job training from the workplace to schools, from the corporation to the individual, is not new, of course. It’s a shift too from a public investment in education for the betterment of society to one in which individuals are responsible for all the risks and rewards that education might offer. The stakes are incredibly high – there’s no social safety net, after all. And no doubt, that’s why someone recently told me that, by opposing AI in education, I was engaged in “malpractice” – negligent in my responsibilities to students and the future.

Speaking of AI literacy, Dan Meyer seems kinda skeptical about two recent studies of AI in education. He calls them big studies in the headline but… are they? It’s one study and one summary of a study yet to be published. Maybe one thing we all need is some research literacy? The summary of unpublished research which purports to show a large effect size for a lesson on antonyms. Apparently by getting a license for MS Copilot, an after-school tutor, training for teachers, and booklets for students these students improved by two years. On antonyms. Dan already points out that the study may not disentangle all these treatments, but I have a broader question which is, how does this work, exactly, with antonyms. Like, how is one kid two years better at knowing opposites to words than another? Isn’t this just a vocabulary exercise? Also, maybe they didn’t have proper controls? Anyway, the other study says teachers save time by using ghat gpt to help in their lesson planning. They saved about 30min on average but there were “last mile” problems. Neat.

One of these days I’ll have to wade into the reading wars with another multi-post series. Until then, here’s an upcoming book that is trying to urge us to look beyond the foundational stuff and rethink more broadly what it means to read successfully. As someone once told my wife, if you want to do stuff, you gotta know stuff. I think that holds true for reading comprehension.

That’s all for today. Thanks for reading! Part 2 next week: the Ohio model.