- Scholastic Alchemy

- Posts

- How did we get here: Götzen-Dämmerung

How did we get here: Götzen-Dämmerung

How to reform schools with a hammer

First, some housekeeping. Welcome to Scholastic Alchemy, a weekly newsletter where I write about education and share a handful of interesting links at the end. My goal, at least right now, is to write about how the US arrived at the current moment in education, a moment where it seems like everything we know and trust about schools is about to go out the window. If you’re interested in this kind of thing, please subscribe. I plan to put up the paywall in early March. If you do not like Substack as a platform, I will be publishing a parallel version using Beehiiv.

Educational Idolatry

The title comes from Nietzsche — the twilight of the idols — and his attempt to reconfigure values that he felt were leading German society astray. I’m not going to summarize the whole thing here. Go read it for yourself. I want to invoke Nietzsche for three reasons. In Nietzche’s writing he questions the idols of his day which appears to my reading to be both systems of thinking about values, culture, and ethics (religion, caste, politics) as well as individuals in society (politicians, professors, the French). Last week I said the topic of this week would be the role of billionaires and philanthropies in education reform. I think a large portion of the policy apparatus idolized these people and organizations. Idolized, perhaps, in the biblical sense, of worshipping something earthly and false instead of what is true and divine.

Which brings me to the second reason I’m referencing Götzen-Dämmerung here: its actual argument is probably somewhat opposed to what I value. Indeed, when Nietzche writes about college professors he makes it clear that only the absolutely smartest and most accomplished should be teachers (though his criteria are seeing, thinking, speaking, and writing, which seems funny today given how derided the humanities have become in the US). Their students, meanwhile, should also be the most exceptionally gifted and the average masses have no need of higher education. When Nietzche rejects Socrates and Plato, we have to remember that he is rejecting the founders of western schooling. School, as an idea, derives from Plato’s academy. Even today we employ the Socratic method when teaching. I think, the view of our educationally involved billionaires and philanthropists is deeply skeptical of school as an idea. As I wrote about with standards last week, much of what passes for reform is a questioning of teachers’ qualifications, of schools’ capacity to evaluate and assess their students, and of the political nature of schooling as democratizing. They are promoting a vision of social engineering through schools that would seem right at home in the parts Götzen-Dämmerung both lauds and criticizes. Also, I have to point out that, as a Prussian, Nietzche would have been among the first in the entire world to have grown up in a society with compulsory primary education and it’s really telling that he doesn’t object to that. As with many things, the nuance and detail of his argument is lost to reformers desire to be great men who lived with vitality and free from the degenerate kinds of morality that Nietzche identifies.

Finally, the third reason I’m bringing in Götzen-Dämmerung and Nietzche is that he’s simply very popular among the reformist set. Whether they have a solid grip on his philosophy is a whole other question. And, you know, maybe I don’t either. I’m just a guy writing on the internet, not a philosopher and Nietzche scholar. Then again, that doesn’t stop them! Either way, the people and organizations pressing for education reform felt they were doing so much as Nietzche felt he was philosophizing: with a hammer. There’s reason to doubt that this was actually the case until very recently but hammer away they did.

We’ve been here before

You may notice a pattern in my writing whereby I look into the past and bring forward relevant bits to make the point that so much of what seems new today is really part of a longer-term conversation between competing views of education and its goals. Certainly, with Nietzche we have a fight set up between a meritocratic-elitist view and an egalitarian view that Nietzche negatively associates with ancient Greece and with Christian morality. That dispute continues and right now we are hearing a lot from conservatives in the US government that the meritocratic-elitist view is coming back. Until very recently, however, there was a strange hybrid position favored by conservatives and some liberals whereby reformers tried to implement something that looked like meritocratic egalitarianism. If you’d like a long read that covers the political positioning around education reform from about 2000-2016, I recommend Matt Yglesias five-part series, The Strange Death of Education Reform. I will note that I don’t entirely agree with his analysis, and I think he is too credulous toward reformers — the idols. Still, it’s worth reading. What I’d like to point out here is that he nicely summarizes the weird meritocratic egalitarianism oxymoron that seemed to define nearly two decades of top-down reform.

I think Obama’s framing of school quality as “the civil rights issue of our time” was probably a bad idea. But in the literal sense that people go to school when they are young and then do other things later in life, educational inequality is, mechanically, the precursor to many other forms of inequality. And it’s challenging to have a coherent discussion about anything related to racial inequality in the United States that doesn’t at least acknowledge the point that the achievement gap, per Hayes’ account, was at one time a major focus of the public discourse. ...

That’s in part the legacy of having abandoned education reform. Yet at the same time, the education reform claim that schools could close the racial achievement gap was an exercise in massive overpromising.

This should seem familiar to anyone who’s been following along with the ‘How did we ger here’ series I’ve been doing. What Yglesias points out, though, is accurate. By reforming schools, the hope was that poor, urban, youth of color would perform comparably to their white peers. Moreover, that performance equality was not just test scores. Those poor youth of color were supposed to grow up and have the same levels of educational attainment, income, and lifestyle. Remember, for these reformers, education creates the economy, the jobs, and the opportunities. This is the egalitarian outcome. But there was also a meritocratic half, namely standardization, measuring achievement, and accountability.

Billionaires know best

I pointed out last week that one of the major animating forces behind standardizing education was a constellation of non-profits, philanthropies, and the billionaires who funded them. Like everything else I write, this is nothing new. In the US we use a system of “credits” for determining how much a kid achieves in both secondary and post-secondary settings. So, like, a state may require that students earn 4 credits of ELA, Math, and 3 of science and social studies in order to graduate from high school. Each credit is usually a full year of a course. In college, meanwhile, courses may be worth 3-4 credits and you’d take several in a typical semester earing 15-18 credits. This system is the product of early 20th century education reforms that resulted from the pressure of the Carnegie Foundation — yes, that Carnegie! It was a push for standardization in teacher pay and an increase in their accountability.

The history of education in the US is littered with reforms both successful and failed. My favorite recent example is the Gates Foundation which Bill Gates and his now ex-wife, Melinda, launched in 2000 just as the anti-trust measures against Microsoft began heating up. It’s good to look like the good guy and improve your reputation. Anyway, the first major educational initiative they pursued was called “Small Schools.” The idea, drawn from the advocacy of Deborah Meier and Ted Sizer, was that high schools should be smaller.

Then in the late 1990s the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation began supporting small schools on a broad-ranging, intensive, national basis. By 2001, the Foundation had given grants to education projects totaling approximately $1.7 bil lion. They have since been joined in support for smaller schools by the Annenberg Foundation, the Carnegie Corporation, the Center for Collaborative Education, the Center for School Change, Harvard’s Change Leadership Group, Open Society Institute, Pew Charitable Trusts, and the U.S. Department of Education’s Smaller Learning Communities Program. The availability of such large amounts of money to implement a smaller schools policy yielded a concomitant in crease in the pressure to do so, with programs to splinter large schools into smaller ones being proposed and implemented broadly (e.g., New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Seattle).

-Wainer, 2010, p.11

The theory was that a smaller school was easier to manage and encouraged better, more personal relationships between students and staff, therefore encouraging community. Importantly, this was targeted at poor urban schools full of kids of color.

“If we keep the [high school] system as it is, millions of children will never get a chance to fulfill their promise because of their zip code, their skin color, or the income of their parents.”

-Bill Gates, National Educaton Education High School Summit, 2000

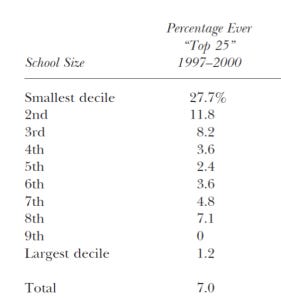

To back this up, the Gates Foundation commissioned a study of the performance of small schools. They produced a chart noting that small schools were overrepresented in the top performing 25% of schools in North Carolina. It turns out, there was an error.

The error is a well-known one to statisticians and was later verified by real, non-Gates payroll researchers: failing to account for differences in variance. Small schools have higher variance than large ones. Their central tendency is, you might say, weaker because a few high or low scores will have a larger impact on the overall average. This would mean that given a proper sample of small schools across a proper timeline, you’d also see schools overrepresented in the bottom 25% of schools.

That $1.7 billion dollars was an attractive carrot, however, and funded the establishment of nearly 2000 small schools by the 2003-4 school year as well as enabled the closure of 400 traditionally sized schools. The programming and funding lasted through about 2008 but in 2005, the Gates Foundation suddenly announced it was changing its focus away from small schools and toward other school improvements like better teacher quality. According to Wainer, “the lead author [of the Gates study] concluded, “I’m afraid we have done a terrible disservice to kids.” Expending more than a billion dollars on a theory based on ignorance of De Moivre’s equation suggests just how dangerous that ignorance can be.”

You’d think that a failure like this would 1) shrink Gates’ ambitions and 2) convince people to place less trust in his efforts. After all, shouldn’t a very smart man with lots of money be aware of basic statistics? Shouldn’t he at least employ people who are aware of basic statistics? Over the next decade the Gates Foundation continued to be the largest funder of school reform efforts in the nation and put its name and billions of dollars behind a myriad of programs. Most famously, Gates helped spearhead the development of the Common Core State Standards and supported the Every Student Succeeds Act. One of his next biggest programs was to use accountability to improve teacher quality. After spending half a billion dollars and upending the functioning of schools around the country for years, the reform efforts were found to have failed.

Of course, Gates wasn’t alone. In 2010, Mark Zuckerberg famously spent $100 million failing to improve Newark, NJ’s schools. The $100 million was, of course, only in matching funds. You see, the district had to raise $100 million to receive his $100 million. Against all odds, they did. With the support of Democratic Mayor (now Senator) Cory Booker and Republican Governor Chris Christie, Zuckerberg expanded charter schools, based teacher pay on value-added measures which were based on students’ test scores, and cut administrators and office staff to improve efficiency. While some test scores went up following a precipitous decline, there were also substantial changes to school enrollment, community income levels, and policy over the course of that same period. It’s hard to know if money was well spent. The impacts were mixed, at best, but were deeply unpopular with the local community.

If you’ve been paying attention, these kinds of reforms have turned public opinion against schools for some time now, or at least against a federal role in schools, opening the door for today’s scholastic arsonists. Even so, the list of expensive failures is a long one and includes many of America’s wealthiest people. Lauren Powel Jobs has not yet successfully “disrupted high school.” After Newark, Zuckerberg tried and failed again. Michael Bloomberg’s charter school efforts have floundered. Netflix CEO Reed Hastings likes charter schools too and wants to use software to stream education right into kids’ brains. We are idolaters indeed.

Improvers of Mankind

These unrepentant meddlers may see themselves as the kind of vital, self-driven, self-made men who are charged with making the world a better place even, perhaps, against the wishes of a decadent, fallen society. What I think is truer, however, is that these men are the idols Nietzche seeks to smash with a hammer. America’s early 21st century reformers of education are telling a moral story of the sort that Nietzche would object to. It is a salvific story in which equality and social improvement comes about through standardized management of the human condition by schools. Rather than promote individuality, instinct, and cultivate the kind of intense humanity that Nietzche sought to free from imposed morality and reason, these reformers are doing precisely those things: One test, one curriculum, one standard, all under a veneer of school choice and merit where markets and accountability select for the best. I’m sure Nietzche would absolutely love a school system in which students took more than 100 standardized tests over the course of their time in the classroom.

Chapter four of Götzen-Dämmerung features what Nietzche calls the Four Great Errors. These are each errors related to causal relationships and I think we can see them present in education reform.

Confusing Cause and Consequence. For Nietzche, this was a religious problem whereby moral behavior yields happiness when, in fact, happiness yields moral behavior. Our school reformers are the same as the church. They believe that their reforms are moral, success in school is a moral imperative because it will lead to a better society when, in fact, the qualities of society are what drive success in school (remember the flawed reasoning about human capital I wrote about).

False Causality. One of Nietzsche’s big points is that free will is something of an illusion. He rejects the psychological idea that our will creates action or that our spirit and ego cause anything. Instead, they are sort of byproducts of our experience of events. He disagrees with religious moral accountability on these grounds. Educational accountability also seems caught up in false causality. Accountability policies are for teachers and schools, not for kids, but we test the kids in order to hold schools and teachers accountable. If their teachers just care enough, they’d choose to teach better, and their kids’ outcomes would improve. To say nothing of factors outside of teachers’ and schools’ control.

Imaginary Causes. Nietzche thinks that we falsely attribute the cause of something to the first idea we have about it. So it is with education reformers. They see a small school that is successful and the big idea they have comes from noticing its smallness. This smallness becomes a moral story they tell about schools in general, it becomes a causal mechanism whereby all schools are made better and society saved. This belief has real and negative consequences in the world, but we ignore challenging those ideas because challenge makes us uncomfortable and necessitates self-deprecating analysis. (This is oddly reminding me of Dewey who argues learning requires discomfort and disturbing oneself from surety, so one goal of a teacher is to promote productive discomfort.)

Free Will. Nietzche doesn’t believe in free will. At least the Nietzsche writing Götzen-Dämmerung doesn’t believe in it. Now, this is probably my limitation as a non-philosopher, but I don’t see a huge difference between the Error of Free Will and the Error of False Causality. Both talk about will and accountability. One new point Nietzche makes here is that free will is used primarily to cast negative judgements on people who do not conform in order to make society dependent on those doing the judging — religions, for him. Leaders use the assumption that people have free will to justify their domination of those people on the grounds that they are immoral and thus deserving of that domination. What does that have to do with education reform? I’ll just leave this here:

Since we’re on the subject of Bush and reforms that weren’t all they were cracked up to be, anyone remember the Texas Miracle? As governor of Texas, Bush had overseen a state takeover of the city of Houston’s public schools because too many kids were “failing” a standardized test (he did NCLB in Texas before bringing it to the whole country). The reforms included more teacher accountability, school choice, pruning staff, and increased prep for standardized testing. Texas began touting gains made by those Houston schools and Bush gained a lot of credibility around education. He campaigned on the Texas Miracle when running for president. But it turns out that the miracle was probably data manipulation whereby schools systematically underreported dropouts and pushed known low performers off the tests, often by simply not marking them present and then sending them to the library on test day. Later, when Houston’s scores were compared with other Texans, there seemed to be little change.

''Is it better or worse than what's going on anywhere else?'' said Edward H. Haertel, a professor of education at Stanford University. [who reviewed the scored for the Times] ''On average it looks like it's not.'

I see versions of all four great errors here.

The hammer speaks

We continue to allow idols to lead our education reforms in some kind of bizarre educational eternal recurrence. Gates and co. are not gone but they have taken a back seat, limiting themselves to selling software and junky AI products that their own research tells them will undermine students’ education. They’ve been replaced by a more ideological group with major structural change as its goal. You can read a critical overview here. What I wish to point out is that these new reformers, if you can call controlled demolition a reform, are cut from the same cloth as the previous group. They’re all incredibly wealthy, both of Trump’s secretaries of education have been billionaires. They see themselves as responsible for saving society from “decadence” and moral decline. Yet, I don’t think this new group would make Nietzche happy either. As much as they might talk of merit and ending programs for weaker, poorer, and marginalized students, the Trump administration is also working to promote the “return” of Christian values to schools. Trump’s reformers certainly aren’t in favor of Nietzschean style thoughtful independence, individualism, or free expression with their banning of words from scientific inquiry, banning of books, and stripping content from pedagogical materials. No, these reforms may be different, and the reformers may be a new set from the same elites, but they too are idols. Sadly, our government is going to follow this set blindly into the next phase of failed reforms.

Normally I’d despair but in the spirit of Nieztche’s writing, I’ll point out that this, too is bound to end. Eternal recurrence means the cycle reverts by its very nature. The wheel turns and so on. One thing we can learn from the principle of scholastic alchemy is that reforms often do not turn out like intended. Reformers fail to understand the complexity and depth of schools, their interconnectedness with local and national communities, or the intrinsically social nature of learning. While we can, and should, lament that failed reforms harm children who might otherwise have done better, we can also celebrate those failures as a chance to do otherwise now. I have no idea which Trump reforms will stick, which will fail, which will be harmful and which (if any) will be helpful. What I do know is that we’ve seen time and again that following an idolatrous path inevitably leads to their failure and our chance to return to what works.

O man! Lose not sight!

What saith the deep midnight?

"I lay in sleep, in sleep;

From deep dream I come to light.

The world is deep,

And deeper than ever day thought it might.

Deep is its woe—

And deeper still than woe—delight.

Saith woe: 'Pass, go!

Eternity's sought by all delight—,

Eternity deep—by all delight!'"

O Mensch! Gib acht!

Was spricht die tiefe Mitternacht?

»Ich schlief, ich schlief—,

Aus tiefem Traum bin ich erwacht:—

Die Welt ist tief,

Und tiefer als der Tag gedacht.

Tief ist ihr Weh—,

Lust—tiefer noch als Herzeleid:

Weh spricht: Vergeh!

Doch alle Lust will Ewigkeit—,

—will tiefe, tiefe Ewigkeit!«

Links

*Note: not always about education

Kendrick Lamar’s halftime show at last Sunday’s Superbowl was probably one of the greatest acts of American protest speech and civil disobedience since the 1960s. I’m still trying to decode all of what was in there but Kendrick and his team of choreographers and performers were clearly operating at multiple levels of meaning. Hint: it’s not just about his feud with Drake. If I were teaching media literacy, literature, history, or civics, this would have been in my lessons this week.

Elon Musk, under the guise of improving government efficiency, seems to be going from department to department and closing everything he possibly can. This week, among other things, he announced closure-inducing cuts to the Institute of Education Sciences. I think the typical take represented in the quote below is bad but misses something fundamental.

Less than two weeks after the release of new federal testing data showing reading achievement at historic lows, the cuts were likely to hit research intended to answer questions about some of the biggest problems in American education since the Covid-19 pandemic, such as absenteeism and student behavioral challenges.

What’s missing is a larger point that conservatives don’t want to know if schools are good. I know, I know, that seems like invective but it’s true. At every turn, despite advocating for decades that public schools should be subject to ever-stricter standards of rigor and accountability, they have steadfastly refused to expand those accountability measures to private schools receiving government funds. At a deep level, I think they understand that accountability measures taken too far encourage people to lose faith in public education and move to private. Now that conservatives have more or less achieved victory in moving ahead with privatization, there’s no need for research or studies of effectiveness or evidence-based practices or accountability.

Speaking of DOGE, since they’ve been digging around in both the Department of Education and the government’s payment systems, someone noticed that they’ve accessed student loan data and sued them. This is, apparently, a violation of the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), but it’s important to note that you, an individual, don’t have standing to sue for violations. I’d imagine this case gets tossed out. Also, if someone on social media tells you this means you don’t have to pay your student loans, they’re wrong. Don’t listen to them.

I’m not exactly sure how I came across Mike Males’ Substack but I am glad that I did. Mike is a researcher for the Center of Juvenile & Criminal Justice and co-writes the debunking website Youthfacts.org which “is dedicated to providing factual information on youth issues –- crime, violence, sex, drugs, drinking, social behaviors, education, civic engagement, attitudes, media, whatever teen terror du jour arises. Since we emphasize demonstrable fact over teen-bashing emotionalism and interest-driven propaganda, the information you find here will be dramatically different than in the major media and political forums.” Usually this kind of statement makes me skeptical so I looked him up and his work seems legit. This post was especially eye opening. If you asked me prior to reading it, if teen suicide was going up or down, I would have said up. That does not appear to be the case!

I haven’t had a chance to listen to this podcast in full, but I’ve found it interesting so far. So much of the 2000-2010 moment seems to have been a preview of what the US is experiencing now.

What I especially noticed was the part about how universities as institutions don’t have a good sense of how to handle a world of alternative facts and seem to fall back on safety — public safety, psychological safety, property safety, all sort of lead to heavy handed crackdowns.

Thanks for reading!