- Scholastic Alchemy

- Posts

- How did we get here: Standards and accountability

How did we get here: Standards and accountability

If you start your story in 2001, you're missing the larger trend

First, some housekeeping. Welcome to Scholastic Alchemy, a weekly newsletter where I write about education and share a handful of interesting links. My goal, at least right now, is to write about how the US arrived at the current moment in education, a moment where it seems like everything we know and trust about schools is about to go out the window. If you’re interested in this kind of thing, please subscribe. I plan to put up the paywall in early March. If you do not like Substack as a platform, I will be publishing a parallel version using Beehiiv. You’re here, though, so don’t worry about that last bit.

Standards or lack thereof

The last two posts detailed how the political system here in the US coalesced around a set of limits for education reform. These limits, informally in place from about 1990 to 2016, meant there was little political appetite for systemic overhauls of school structure and funding. Instead, changes were going to be focused on curriculum, on accountability, on standards, and on “innovation” in charter schools. That consensus has thoroughly collapsed and has been replaced primarily by conservative activism pushing for privatization and public funding of religious schools. Political scientist David Menefee-Libey called this period of consensus the Charter School Treaty. While I think he more or less correct about how the politics of school reform played out for over two decades, that doesn’t mean changes within that treaty’s framework were unimportant or minor. You can change a lot about schools without entirely changing the structure of school systems or how they’re funded.

If there was one thing that defined school reform during the treaty period, it was the establishment and then abandonment of standards. Yet, if you ask education folks today, they’ll usually point to No Child Left Behind, George W Bush’s reform package that was signed in 2002 and went into effect over the subsequent three years. Arguably just as impactful, though, were the Common Core Standards that were adopted state by state from about 2007 to 2015. Today’s post is my attempt to draw out a longer history behind the standards movement as well as why it, too, was subject to Scholastic Alchemy.

19th Century Standards for the 21st Century

I think the first thing you realize when reading what standards advocates have said over the years is that none of them believe teachers should be trusted. For example, Boston schools in the 1840s began replacing oral examinations, in use in formal education since at least the Middle Ages, with a written exam. Horace Mann, one of the prime movers in American education, felt that written exams were superior.

When the oral method is adopted, none but those personally present at the examination can have any accurate or valuable idea of appearance of the school…Not so, however, when the examination is by printed questions and written answers. A transcript, a sort of Daguerreotype likeness, as it were, of the state and condition of the pupils’ minds, is taken and carried away, for general inspection. Instead of being confined to committees and visitors, it is open to all; instead of perishing with the fleeting breath that gave it life, it remains a permanent record. All who are, or who may afterwards become interested in it, may see it.

correspondence quoted in Caldwell & Courtis, 1923

Mann is saying that those present at the exams cannot be trusted and that a written record allows for independent accountability, transparency to the public, and permanency. The fear Mann and others had was that different students would learn different things because they had different teachers. This, Mann argued, would make them “different men.” Teachers were at risk of showing favoritism in assessment or even cheating to help the student. This attitude remains at the core of the standards movement today. Education, they argue, is too important to be trusted to teachers and the quality of their students must be judged independently and made known to the public. Mann and the Boston School Survey, as the exam became known, birthed the first standardized test in the United States, one that lasted until this year, but didn’t lead to a nationwide trend of establishing standards. (Wait, we had standardized high school graduation tests in the 1840s? YES! This shit didn’t start in 2002!)

Believe it or not, it was the advent of mechanically mass-produced pens and pencils in the 1870s that began a larger swing toward written exams (Travers, 1983). By 1900, industrialized production of writing instruments drove down prices such that even poorly funded schools and families could afford and maintain them (Petrosky, 1989). In fact, when I lived in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, I often walked by the Everhard Faber pencil factory that was the largest in the world in the 1870s (now condominiums).

The pencils at the top of each pillar have no erasers! via Brooklyn Relics

Apparently, the founder came from a long line of pencil craftsmen in Bavaria, stole their designs, and came to New York to make his fortune manufacturing pencils. Shortly thereafter, Faber was involved in a lawsuit alleging that he copied a particular patent: putting erasers on the end of the pencil. The case literally went to the Supreme Court who threw out the patent. Putting erasers on pencils proved to be an essential innovation for schools, allowing a single item to both write and erase itself. This gives us another important aspect of standards: they are closely connected with innovation, efficiency, and mass production. 120 years later, the Faber-Castel (yes, the same Faber family back in Germany also started a major pencil business) bought the company and sold the factory.

IQ and No. 2

Educationists, as proponents of what they saw as the science of education (early versions of what you might call today educational psychology and cognitive science) called themselves, developed standardized testing for a wide variety of applications but the most influential was Edward Thorndike. Although he did not develop the IQ test, Thorndike (and the less well-known Lewis Terman) successfully argued that IQ testing belonged in schooling and oversaw the use of IQ tests in many of the newly compulsory school systems in the northeastern US in the first quarter of the 20th century. This represented two kinds of standard, the first being a set of standards that laid out what was considered intelligent, and the other being a standard of educational assignment based on the outcomes of these tests. Students scoring highly would be placed in more academically rigorous settings while those scoring lower would be placed in settings designed to prepare them as unskilled laborers. Rather than today’s standards, which set a minimum level to be achieved, the role of standards in the early 20th century was to evaluate for placement.

In many ways this use of standards manifested as a search for efficiency. Stephen Colvin, a contemporary of Thorndike and Terman, felt that schools were wasting time and resources on youth who were not biologically capable of the work. A standardized system of testing would allow experts (notably teachers and school leaders were not experts) to decide where they should go and what they should learn. Around that time, elementary education professor Frank McMurry connected standardization, efficiency, and curriculum.

The curriculum will be good to the degree in which it contains problems—mental, moral, esthetic, and economic—that are socially vital and yet within the appreciation of the pupils; and its method of presenting that curriculum will be good to the degree in which it exemplifies the methods of solving problems found most effective by the world’s most intelligent workers.

(McMurry, 1913)

Let’s draw out a few terms here to clarify. First, look at what he thinks schools are doing: mental, moral, esthetic, and economic education. Seems far more expansive than today’s “school is preparation for work” model, though he does mention workers at the end. Second, these are socially vital — that is, they’re judged by experts to be good for society. Third, they are within appreciation of the pupils — today we’d call this developmentally appropriate. Fourth, we get this point about solving problems deemed effective by the world’s most intelligent workers. That is to say, test questions set up by whoever has high IQ. Somehow, I doubt the laborer bending rails at the steel mill was considered among “the world’s most intelligent workers.”

So, already by the 1910s I think you have all the modern elements of standardization in place. What “we” care about in education is identifying intelligence according to some kind of criteria based on the most successful workers, sorting students according to their performance, delivering appropriate instruction based on that sorting, and making evaluations independent from the interference of teachers and schools, and making results permanent and (somewhat) public. This era has been labeled by some as “the age of standards” (Kenichiro, 2008) and it’s also important to note that it was the age of eugenics, social Darwinism, and progressive social meliorism, all of which were intimately connected with the perceived need to standardize schools. For obvious reasons, the appetite for intelligence-based standards fell out of favor following World War 2 and the use of IQ tests for academic placement in schools faded away by the 1960s. Even the word standard was replaced by norms in mid-century US education (Kenichiro, 2008). Yet, standardized tests remained in place, often as a graduation requirement assessed toward the end of high school. One problem these kinds of tests faced, and the reason we didn’t see them deployed over and over across many grade levels was that issuing and assessing these tests required a lot of time and labor.

The pencil would become quite relevant again because of the development of scantron technology in the 1970s. That year, former employees of the office supplies firm, 3M, got together and came up with the idea of a sheet of paper similar to IBM’s computerized punch cards. Punch cards were initially read mechanically with the holes indicating to the computer a certain code-input that it was programmed to respond to. Updated versions later used light shining through the holes to achieve the same ends but with the benefit of faster throughput. After working with some of these machines, the former 3Mers realized that thin enough paper and dark enough markings could perform the same task but were worried about being sued by IBM who owned the patents. They struck out in a new direction and convinced the state of Ohio to use them for their standardized graduation test. (Wait, we had standardized high school graduation tests in the 1970s? YES! This shit didn’t start in 2002!) Scantron, however, needed another kind of standardization if their product was going to work. They needed students to mark only in specified locations and they needed the mark to be dark enough to block all the light. The No. 2 pencil we all know and love was the perfect choice. Its graphite was strong enough that precise marks could be made, it would not smudge (like No. 1 did), and it produced a darker mark than other firm pencils (such as the god-awful No. 3 and No. 4). Mass standardized, electronically graded tests quickly became mainstream as the SAT and most states and schools adopted this new innovative tech.

Renewing the push for Standards

Today’s version of standards is, at its heart, a return to those 19th and early 20th century ideas about efficiency, distrust of educators, and expectation that independent experts design curricula and assess them. We also see that the wellbeing of society is wrapped up in the purported need for a standardized education. Initially framed as Outcomes-Based Education, this part of the story begins in 1983 with the publication of A Nation at Risk and the launch of a nationwide campaign of school renewal. Schools, according to this view, were insufficiently rigorous and were producing a generation of students incapable of finding good jobs. One rather new aspect of the outcomes-based approach was advocacy for nationwide set of outcomes that schools were required to achieve. Now, this post would stretch on forever if I detailed every standards proposal, but I do think it’s important to list them here and you can ready the relevant wiki:

2001: No Child Left Behind requires all states have standards and that students are given standardized tests at least every other year starting in 3rd grade.

2008-2010: Common Core drafted and begins being adopted state by state, eventually 41 states adopt Common Core.

I’ve written previously that the increasing federal role in education provoked backlash against standardization, testing, and top-down initiatives. Whereas earlier pursuits of standardization were often centered around university researchers (e.g. Terman at Stanford, Thorndike at Teachers College) or local school leaders (like Mann in Boston), the press for standards that started in the 1980s had two major sets of supporters. First, as we see with the list above, are the presidential administrations who often convened panels and committees to produce reports like A Nation at Risk. Second, are think-tanks funded by large philanthropic organizations. For example, one of the leading voices in the 1990s for standards was the National Center for Education and the Economy, an organization spun up by the Carnegie Corporation of New York (you know, the one set up by industrialist robber baron Andrew Carnegie to build all those Libraries because America needed an educated workforce?) and now receives funding from other major philanthropies like the Gates Foundation. Or, as I mentioned in a previous post, the Center for Education and the Workforce which gets funding from the Lumia Foundation whose mission is to increase college enrollment and, yes, the Gates Foundation. The post-1980s standardization movement is more concentrated among these well-funded groups and federal policymakers and remains something of a success story because those reforms were eventually implemented. Critically, they also stayed within the framework of the “treaty” and mostly focused their changes on curriculum and accountability measures rather than wholesale overhaul of schooling. As we saw last week that trend is changing, and some philanthropic money is backing more conservative visions of religious and segregated schooling. I’ll write about the role of philanthropies and billionaires next week.

Backwards is forwards?

As we enter 2025, the new era of standards may be over. States have largely abandoned the Common Core, moving back to their own sets of standards. In many places, schools are moving away from high stakes testing. As I said previously, this is not just a conservative phenomenon, and we can witness backlash across the political spectrum. Back in 2021, Virginia Governor Terry McAuliffe lost to conservative firebrand Glenn Youngkin in part because of the perception that parents should not have a say over their kids’ education, presaging the presidential election three years later. Politico reported,

Youngkin was helped to victory by his opponent, McAuliffe, saying “I don’t think parents should be telling schools what they should teach” — a widely perceived gaffe that Republicans quickly pounced on.

While the concerns at hand were not the state’s educational standards, the attitude among parents and voters was that schools were not sufficiently accountable to the public. Deep blue Massachusetts, the state generally acknowledged to have the best public school system in the country, voted to end the state’s graduation test in a ballot referendum last year. At the federal level, the second Trump administration is blazing ahead with efforts to support vouchers and defund traditional schools, often arguing they are captured by radicals intent on forcing their ideology on helpless children. Pot calling the kettle black, I know! I expect these reforms to mostly fail even though they seem momentarily popular. Localism is very popular in the US, especially when it comes to schools. Most Americans like their local public school. Part of that reason is they feel like they have a say in how it works and can see that what’s happening there is good for their kids.

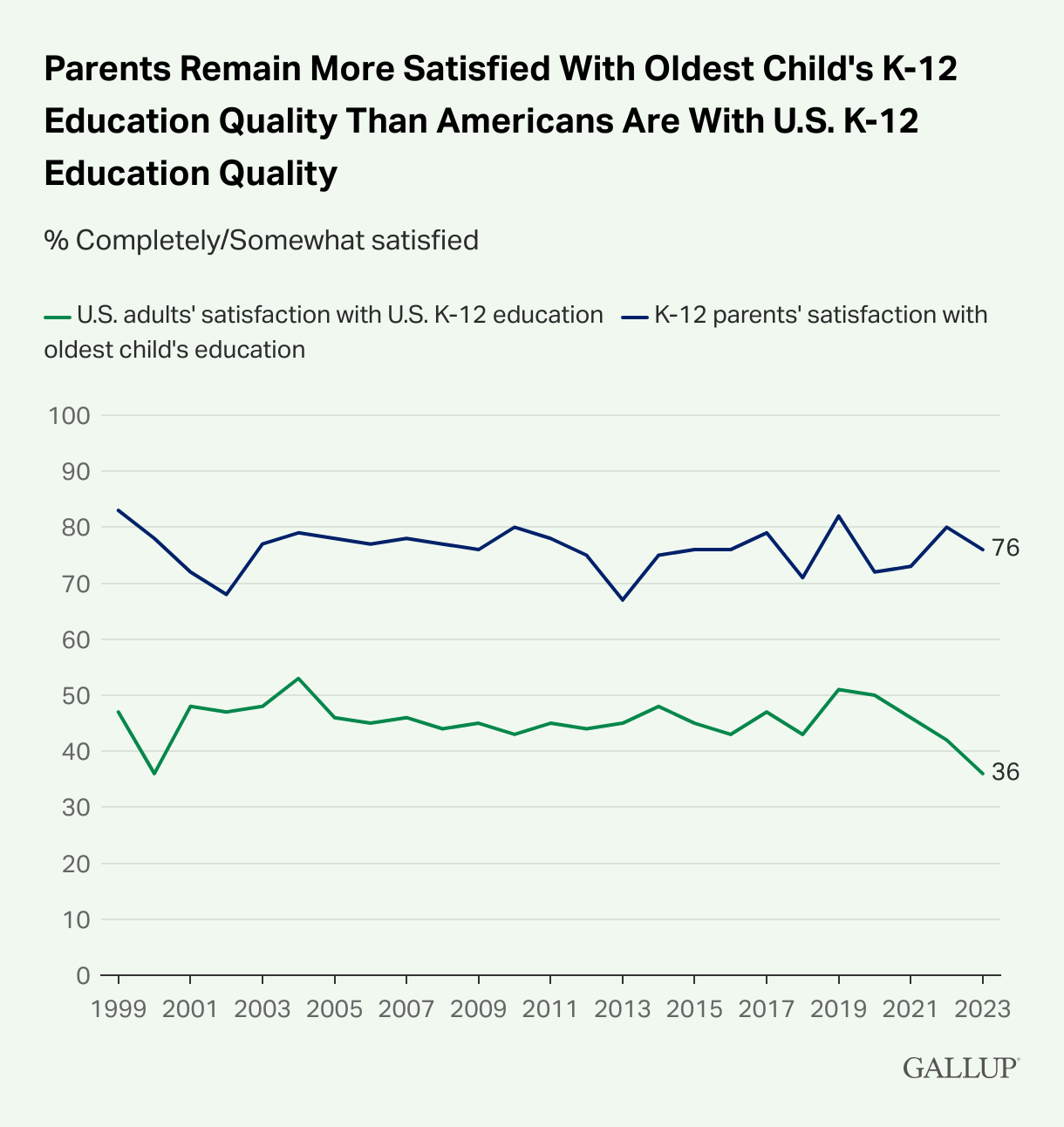

In other words, 76% say they are satisfied with their kid’s school but 64% say they are dissatisfied with schools in general. If this was a factual statement of quality, these stats should be mutually exclusive.

It is precisely because the public likes local control that I think the radical moves to replace public schools will fall apart. Parents don’t have a voice in the functioning of private or charter schools. They don’t have local control if Washington DC or their state legislature sets curriculum along strict ideological lines. I expect they will wise up to that earlier version of standards as “mental, moral, esthetic, and economic” and be turned off. Ultimately, parents are, I expect, going to reject conservative moralizing just as much as they seem to have rejected progressive moralizing. Some lessons, American parents will tell you, belong in the home. This is, after all, Scholastic Alchemy. When it comes to schools, the path we think we’re on rarely takes us where we expect to go.

And, look, because it’s 2025 and reading comprehension on the internet is dead, I need to specify that I’m not writing this because I love “parents’ rights” as a principle. I think parents’ rights is a justification for all kinds of bad policy, including further marginalizing already marginalized kids. That doesn’t mean parents’ don’t like it and it doesn’t mean that their perceptions of those rights should be ignored because they’re inconvenient. Whatever objections I have are beside the point because what’s happening is happening. We’re all along for the ride.

Links

*NOTE: Not always about education.

Although the article came out a little while back, it’s new to me. Educational technology has a 5% problem. The quick version is that companies that make education software need to produce research to support the efficacy of their software. Let’s say you’re Mr. Edward Tech. Ed for short, and you are trying to sell Zearn, or DreamBox, or iReady to school districts. You get some to agree to a pilot study and soon you have a few thousand kids of various characteristics using your software and the software is collecting all sorts of data about how they’re doing. In order to actually know if your software had any impact, you need to focus on the kids who, you know, actually used your software. Kids who didn’t use it can’t tell you anything useful about your product, right? You think about it and establish a “minimum dosage” as a cutoff. Say, 30 minutes a week. You apply that filter, and it turns out only 5% of students used the software 30 minutes a week. Thankfully you started with an absolutely huge number of kids, so you still have a large sample size even after eliminating 95% of the enrollees. For that last 5% of students, you show there’s a nice solid effect size. An effect size that equates to several months of additional classroom time. Hurray, off to the marketplace!

Let’s say you’re not Mr. Ed Tech. Now you’re Mr. Prince E. Pal, the head honcho of a high school. Like principals everywhere, you are playing catch-up after Covid, you’re trying to goose your graduation rate, or any number of challenges a school might face. Ed shows you some slides, a few examples of the program, but the real selling point is that this software can, just by using it 30 minutes a week, add months of learning to your kids. You sign a multi-year contract. You’d be stupid not to! Of course, a year or two later you’re upset because these gains failed to materialize and you’re having trouble getting kids to even log on once a month, much less for 30 minutes a week. You never saw the fine print, that the results of these proprietary studies are drawn from the 5% who actually used the software on a regular basis. You never had a chance to apply that basic research 101 question: what if the sample is meaningfully different from the population?

I like to harp on the concept of scholastic alchemy, the title for this blog/newsletter thing, to remind people that education is just as complex, contingent, and random as any other field. When people start saying “Why can’t schools just ____?” then you should insert scholastic alchemy as your answer.

Anyway, banning cell phones in school is big business now. Probably almost as big as hardening schools. One of the most popular and well-known options is called Yondr, a pouch originally designed for concert venues where, believe it or not, artists and comedians have been selectively banning phones for years. Basically, you put your phone in and close it and then can’t open it unless you press the pouch on a special magnetic unlocker thingy. Well, kids are “hacking” their Yondr pouches to get around the phone bans. I offer two choice quotes:

Some students put burner phones in their Yondrs, says Fran, a middle-school English teacher in Alabama; others lock vapes and weed inside so they can sneak them past bag checks.

People [at one school the reporter visited] were saying the sixth-graders might not be able to go on their annual Six Flags trip because the school was spending so much money replacing Yondr pouches.

Scholastic Alchemy!

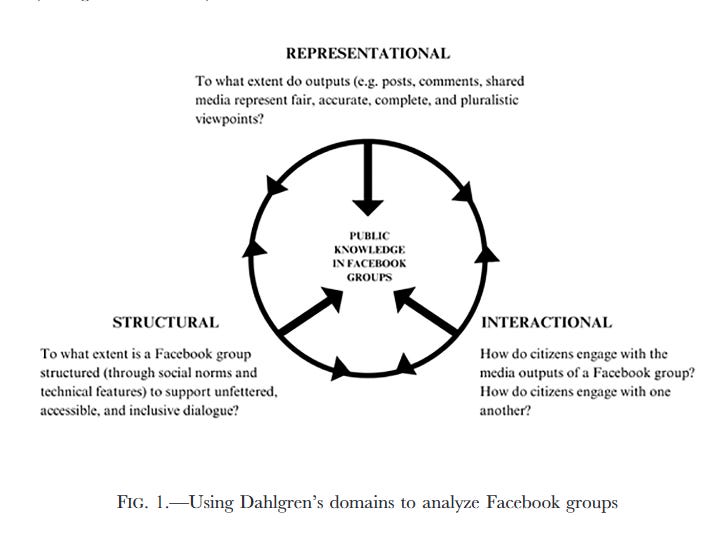

I don’t often link straight up research articles because people don’t read them and they’re paywalled in a way that’s hard to navigate around. If you’re not someone with academic library access, you probably can’t read the current issue of the American Journal of Education. Sometimes, though, it’s super interesting and it also dovetails with some of what I’ve been writing about. Ashley Casey studied how people talked about public schools on Facebook in an attempt to understand how “public knowledge” about local schools is constructed. Here’s a diagram so you know what she’s thinking is “public knowledge”:

Casey, 2025, p.191

She finds that negative posts are ten times more common than positive ones, 40% to 4%, the remainder were neutral. Negative posts also received more interaction, on average, than positives. Like other online spaces, Casey found that a few users generated the majority of posts and comments and that these “special interest users” — they usually had a specific topic or problem they continually posted about, a special interest — were adept at using the platform to drive engagement on their preferred posts.

Although Comment Cathy [pseudonym, obvi], alone, might come off as a disgruntled parent on a mission to discredit the schools, her ability to engage with other parents in the comment section, which ultimately attracts more commenters to the post via the algorithm, creates an air of legitimacy to her claims.

Anyway, here’s the point from the discussion that I really wanted to share because it meshes but challenges what I wrote in the main post above:

Historically, Americans have viewed their own local public schools favor-ably even when they viewed the nation’s schools unfavorably. Recent research finds evidence that this pattern may be breaking down as national talking points undermine public trust in local schools (Bertrand et al. 2023). This study demonstrates the ease with which a small number of political actors can control and shape the narrative around local schools.

Seems bad! Let’s put parents’ phones in Yondr pouches at the end of each school day and make them come to school to unlock them each morning so they have the phones for work.

In the last two posts I wrote about school choice and made what I think is a fairly clear case that school choice is about re-segregating schools and getting the government to pay for religious schools. I thought it would be helpful to share a religious point of view defending the separation of church and state. An evangelical even!

I believe in the separation of church and state because there are numerous Christian sects within our country alone, let alone within the entire world. Each sect has their own unique theology and interpretation of the Bible. So which Christian sect gets to dictate the kind of Christianity that is mandated?

I believe in the separation of church and state because it not only allows the church to be the church and the state to be the state, but it also prevents the church from giving into the temptation to worship political power and allows it to faithfully embody the gospel of Jesus, including speaking truth to the powers of this world. The church simply can’t speak truth to the power of the state when it has become one with the power of the state.

Jesus rejected Satan’s temptation to control the kingdoms of this world and I believe we as his followers should too.

“Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” -Jesus

Amen.

I plan write a lot about the deep historical roots of things that we see as new or current in education, in case you hadn’t noticed. One way I like to give a short history of the federal government’s role in modern US education is to start with school integration and with sputnik leading to big investments in schools for promoting science and engineering. But, as I pointed out in today’s post, a lot depends on where you set the beginning of your story. Derek Black dispels the myth that the federal government never had a role in education by looking at the Founding Fathers, Lincoln, and public education during Reconstruction. It’s racism all the way down.

Thanks for reading!