- Scholastic Alchemy

- Posts

- I'm Skeptical: Learning Loss

I'm Skeptical: Learning Loss

A series about things I'm not quite sure I believe

Welcome to Scholastic Alchemy! I’m James and I write mostly about education. I find it fascinating and at the same time maddening. Scholastic Alchemy is my attempt to make sense of and explain the perpetual oddities around education, as well as to share my thoughts on related topics. On Wednesdays I post a long-ish dive into a topic of my choosing. On Fridays I post some links I’ve encountered that week and some commentary about what I’m sharing. Scholastic Alchemy will remain free for the foreseeable future but if you like my work and want to support me, please consider a paid subscription. If you have objections to Substack as a platform, I maintain a parallel version using BeeHiiv and you can subscribe there.

You may have noticed I took last week off. It was semi-planned. I’d wanted to take a week and hit pause sometime around now but thought I’d do it closer to the end of June. Then some schedule stuff shifted around the Memorial Day holiday and the early part of the week where I usually draft out my posts. One reason I wanted to think about a pause was that I was considering increasing the cadence of posts, maybe something every weekday? I’ll think about that more and see how things look as we go into the summer months.

A New Series of Posts

I’ve been wanting to do another series of posts that can focus on a theme or some overarching idea, much like the How Did We Get Here? set that kicked off this newsletter/blog/thing. One thing I thought would be fun is to take stock of ideas that are very common and influential in education but that I am personally a bit skeptical of. An old example of this would be Learning Styles. If you were in your teacher training anytime between the late 90s and early 2010s, then you probably heard a lot about learning styles. The overall idea was that students could be classified according to their particular style of learning. One student might be considered a bodily-kinesthetic learner who needs to be hands-on and learns best when activities involve movement and manipulating objects. Another student might be a visual learning who needs to see concepts represented through shapes, pictures, and symbols. Teachers were expected to meet these many learning styles by producing lesson content that was multimodal — e.g. that contained opportunities for all styles of learning to access the content of the lesson.

There are many shortfalls to the implementation of learning styles in the classroom. For one, it placed an enormous burden on teachers to write many variations of the same lesson that could incorporate everything from visual symbols to physical activities to written text to rhythms and chants. Another problem is that learning style theory turned out to be wrong. Rather than being something innate in learners, learning styles are probably better thought of as students’ preferences. Moreover, those preferences are shaped by what a student is good at or most comfortable with, so a good reader will prefer written texts while a poor reader may want pictures. As Dewey reminds us, discomfort is an important part of learning. A final problem for learning styles is that it’s not just wrong but educationally counterproductive. Educators who stated that they believed in learning styles also held essentialist beliefs about their students. For example, heritability was never a component of learning style theory, but the teachers felt their students inherited learning styles from their parents. Others saw learning styles as something deeply intwined with students’ brain functions. These translate to an essentialist view of kids as unchanging in their method of acquiring new knowledge and skills, potentially leading kids learning in one way despite it not being the best way for that child to learn.

Educaton is full of these zombie ideas that show up, are disproven, and then refuse to stay in the graveyard of misleading, wrong ideas. This new series is my attempt to show some big ideas that I don’t find super convincing. It took a decade of papers and pushback for learning styles to finally leave the mainstream education discourse. What ideas will we end up rejecting in ten or twenty years? What are tomorrow’s versions of learning style theory? So let’s kick off the I’m Skeptical series.

Learning Loss: What is it?

I should say at the outset that I’m not necessarily saying the ideas in the I’m Skeptical series are out and out false. What I mean when I say that I’m skeptical is that I think the idea could be false, needs more clarification or better data, or that it has some kind of logical mix-up that could mean we’re just chasing yet another thing that correlates with socioeconomic status. The ideas may be more incomplete than false.

Look, I get it. Learning loss seems like an obvious concept. What could I be confused about? Kids miss out on some kind of learning, COVID school closures being the most pressing example, and kids don’t learn as much as they could have if the pandemic never happened. Seems easy enough to understand and, if learning loss were that simple, then I probably would not have anything to be skeptical of here. The thing is, learning loss is a measurement that researchers construct. That construction must, by its very nature, include some things while excluding others. It’s not a conspiracy; it’s just how research works. You can’t include all data everywhere about everything or you’d never have any research.

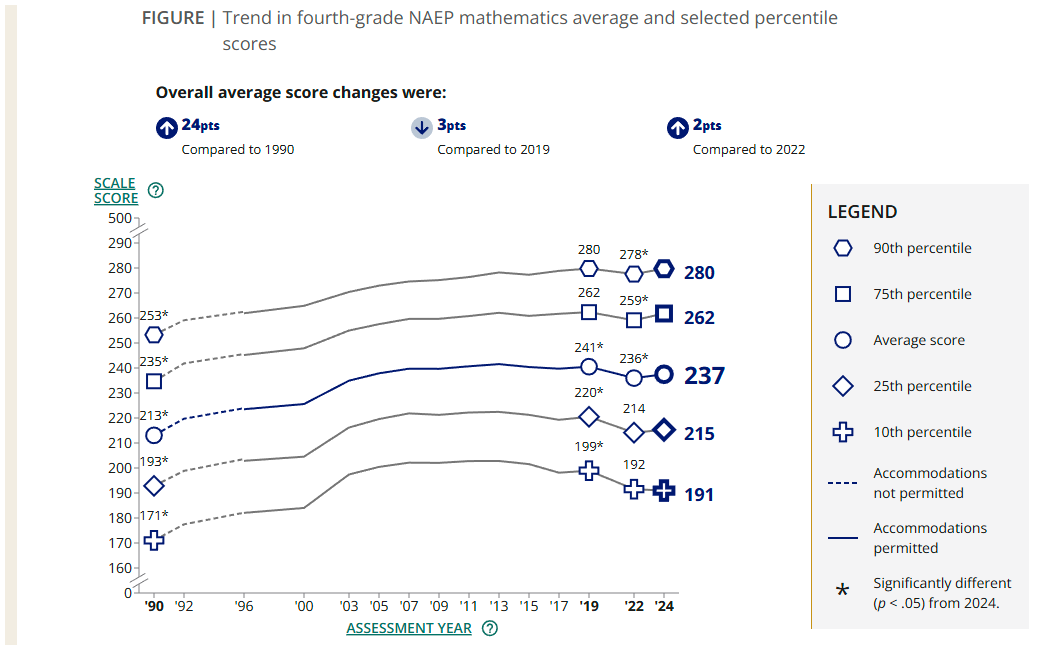

Learning loss, then, is constructed in a few different ways. The first is just testing kids and seeing how they compare with past groups of kids taking that same test at the same stage in their education. So, 4th grade NAEP scores today vs NAEP scores from the last set of tests in 2022 and the ones before the pandemic in 2019. The 2024 4th graders score a bit higher than the kids who took the test in 2022 but lower than 2019, on average, nationwide. The argument is that the kids who have demonstrated lower levels of skills and knowledge on math and reading tests are suffering from learning loss. This is more or less what we see reported on most in the media. It’s the “nation’s report card” after all.

NAEP Mathematics: Mathematics Results

Another version of learning loss to give a pre- and post-test to the same kids and see if they’ve “lost” their learning. The classic version here is testing kids in May and then again in September to see what they lost. Sometimes, though, it seems like people try to make predictions by using the performance of prior cohorts to make an educated guess at future performance. Then they get it wrong. Either way, the operating assumption is that there is some kind of important event disrupting education such as a summer break, disaster, or pandemic and that kids’ performance on tests before and after tells us something was lost. The pre-post version is not mentioned as often in the media but remains consequential in school and district policy decisions.

Finally, the most common way researchers talk about learning loss is by computing how many days of learning kids lose. Rather than reporting on measures of skills or knowledge, researchers create a standardized measure from those other measures to better communicate to the public how much learning was lost. For example, in a study of virtual charter schools, researchers found that students at virtual charters lost “72 days of reading and 180 days of math instruction” compared with their non-virtual peers. How do we get this measure?

To create this benchmark, CREDO adopted the assumption put forth by Hanushek, Peterson, and Woessman (2012) that “[o]n most measures of student performance, student growth is typically about 1 full standard deviation on standardized tests between 4th and 8th grade, or about 25 percent of a standard deviation from one grade to the next.” Therefore, assuming an average school year includes 180 days of schooling, each day of schooling represents approximately 0.0013 standard deviations of student growth.

This measure has the added benefit of not requiring measures before and after some kind of event or waiting and testing a new cohort of kids next year. Literally any quantified outcome can be explained in terms of days of learning so long as you calculate the standard deviation and divide that by the number of days in the school year. Days of learning lost are something we hear about quite a lot in both the media and in policy discussions. Did you know students lost 6.8 million days of learning because of the pandemic? That’s more than 18,000 years of learning! Even worse, the following year kids lost 11.5 million days of learning (32,328.7671 years). Think of all we could have learned in the last thirty-two thousand years if only schools weren’t closed in 2021. I think you’re catching on to my point here thanks to the Institute for Public Policy Research making an earnestly unintentional attempt at argument ad absurdum. There are good reasons to be skeptical of learning loss.

Why I’m Skeptical of Learning Loss

Let’s start with some first principles questions. A good one is, do people actually lose learning? Like, is that a psychological, cognitive, or neurological thing that happens? The answer helps us break away from the simplistic clarity of the learning loss claims. Brains do forget things and there are neuro-chemical mechanisms that make brains forget stuff. The existence of these mechanisms suggests there are good reasons we’ve evolved to forget things. One critical example comes from studies of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. More broadly, though, we have evolved to forget stuff that is not frequently useful to our survival and functioning in human societies.

One neat thing is that the brain also maintains some kinds of learning longer and better than others. There is an old expression that something you’re out of practice with is easy to relearn because it’s “like learning to ride a bike.” That is, once you learn how to ride a bike, you can do it pretty much forever even if you take a long break. I took a bike trip with my parents in 2015 and, despite having not even owned a bike since middle school, I was able to ride a mountain bike through Canyonlands national park on some pretty treacherous terrain for three days, 100 miles, and 3000ft of elevation change. Brains are just like that. You forget a lot but remember some. How it selects and why, I do not know but maybe someone could point to a good overview? Oh wait, that’s the neurotransmitter article linked above.

That brings me to my next first principles criticism of learning loss: why do we only lose math and reading? I’m being a bit tongue and cheek here because this is an artifact of our national policies around measurement AND in our media reporting of them. NCLB only mandated math and reading tests so many states only developed math and reading achievement tests. Despite being defunct since 2017, this policy regime still casts a shadow. For example, here’s how Ed Trust, an education policy think-tank discussed the 2024 NAEP data.

The National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), also known as the Nation’s Report Card, has once again provided a snapshot of how the country’s fourth and eighth graders are doing in math and reading. Many, including EdTrust, rang alarm bells about the precipitous declines in NAEP scores during the pandemic — where scores dropped an alarming 5 points in fourth grade reading and 6 points in eighth grade math between 2019 and 2022. The NAEP results from 2023 showed that unfinished learning from the pandemic was still prevalent. Now, in 2024, there’s a lot of data to sift through, but the latest results tell a familiar story: our nation’s students need more support.

Nationally, scores remain below pre-pandemic levels, and in fact, scores in 4th grade reading and 8th grade math are now where they were 30 and 25 years ago, respectively.

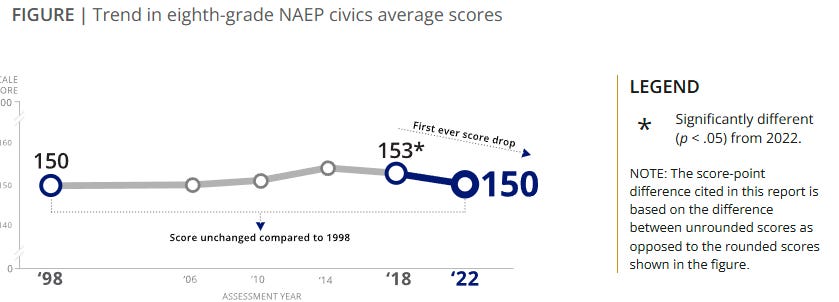

You’d never know that NAEP also tests kids on History, Civics, the Arts, and Science, albeit less frequently, even though they also display declines. History, for example:

source

Now, some of this is because the other subjects are less frequently assessed but I think that is also emblematic of the problem. Our testing apparatus at both the federal and state level is heavily focused on reading and math so our policies are focused on reading and math and then when we have “learning loss” we only document it happening in reading and math. Nobody has ever lost learning in art class. Nobody has ever lost learning in physics or chemistry. Really? Is it like bike riding and our brains are just somehow attuned to remember science but not math and reading?

When considered in light of some first principles, the entire concept of learning loss seems under-theorized and incomplete. It doesn’t offer us a good explanation for why some kids “keep” their learning and others don’t. It can’t help us understand why some subjects may be better remembered and others more easily “lost”. Indeed, even the way we study learning loss is so wrapped up in education policy decisions made two decades ago that we don’t even bother to regularly collect or analyze data on all the kinds of learning that students do in school. The new measures we do develop are often semi-useful attempts to make test score statistics more digestible for the public: days of learning. But those constructs are drawn from the same limited testing (how many days of social studies learning have we lost? Anyone?) and can be turned into such absurdities that it’s hard to know what to do with them at all. How do you even begin to fix 11.5 million days of learning lost? What is this measure accomplishing?

Why I’m Skeptical Beyond First Principles: Other kinds of Learning Loss don’t replicate.

If you were a kid in the US in the 90s and early 2000s you probably remember Summer Reading. You’d get a list of twenty books or so and have to pick a few from that list and write a report about them or maybe take a test when you got back. Many schools still do this. The whole reason these programs exist is to combat learning loss over the summer. The summer slide, teachers sometimes called it. Kids are out of school for two months and they come back having lost some learning from last year. We give them some work to do over the summer, and it helps stave off the loss. Moreover, there is an expectation that poor students, students of color, and boys lose more learning over the summer than their wealthier, white, and female peers.

It turns out that summer learning loss probably isn’t real. Despite there being a large literature since early last century, much of the research on summer learning loss has methodological flaws that, once fixed, erases the learning loss.

After reviewing the 100-year history of nonreplicable results on summer learning, we compared three recent data sources (ECLS K:2011, NWEA, and Renaissance) that tracked U.S. elementary students’ skills through school years and summers in the 2010s. Most patterns did not generalize beyond a single test. Summer losses looked substantial on some tests but not on others. Score gaps—between schools and students of different income levels, ethnicities, and genders—grew on some tests but not on others. The total variance of scores grew on some tests but not on others. On tests where gaps and variance grew, they did not consistently grow faster during summer than during school. Future research should demonstrate that a summer learning pattern replicates before drawing broad conclusions about learning or inequality.

Remember, pandemic learning loss measures are based on measures developed for summer learning loss.

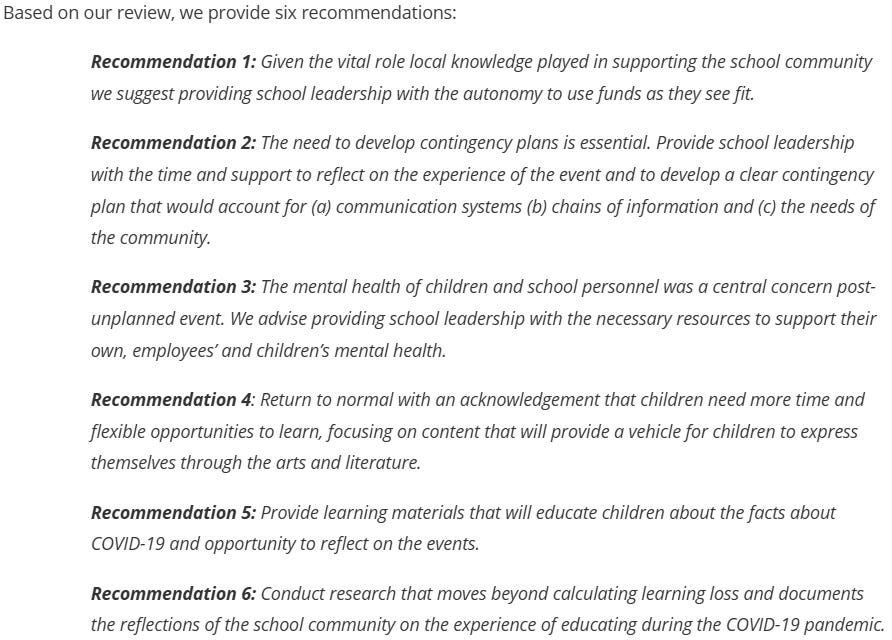

Other kinds of learning loss, such as those following natural disasters, have also been questioned in recent years. Some researchers have, for example, sought to reframe learning loss as learning disruption to better characterize the nature of the challenges students are going through.

In this context, it is useful to consider whether learning is best understood in terms of a steady linear progression that time out may significantly disrupt, or rather moves at different rates and paces over time. Kuhfeld and Soland (Citation2020) argue that the assumption that learning growth is linear is “tenuous at best” (p. 24) and often faulty. In a study of two years of longitudinal data on reading achievement in state-mandated tests, Kuhfeld (Citation2019) found that, by looking at two results, collected at either side of the summer, many students appear to “lose” learning. However, using data from more points in time, results are more variable than the learning loss literature would suggest: up to 38% of students gain during time out of school. Counterintuitively, socio-economic status explained only 1% of the variability in these results. The study also showed that the amount gained during the previous academic year was the best predictor of summer loss, and those who lost most regained fastest. This supports the learning theories such as those proposed by Thelen and Smith (Citation1994), and Siegler (Citation1996) who both suggested that learning is best characterized by overlapping waves of progressions and regressions over time.

They produce a helpful set of recommendations.

source

Notice the focus is not on math and science. Indeed, the researchers ask their peers to move beyond calculating learning loss and seek more contextualized and community-based understandings of what happens when schools close or someone undergoes a disruption to their learning.

All of this dovetails nicely with what I’ve written about previously when I asked, what happens when school is flooded on test day? I closed that post by saying that

[w]e’re so focused on academic outcomes that, as a society, we’ve forgotten that schools need to respond to more than just our students’ academic needs. The disasters aren’t going to stop. Indeed, returning to “normal” might never actually, truly be possible given the increase in frequency and severity of natural disasters and the long lasting impacts of these events on students’ well-being. Throw in other traumatic events - school shootings, economic-induced homelessness, international migration and asylum, and we have to expect our students and our schools 1) to have more disruptions to their learning and 2) to require more material and psychological support than we are currently providing. Pretending like schools will just continue on as normal is no longer an option.

Learning Loss: It’s Scholastic Alchemy!

So many of the foundational assumptions around post-pandemic learning loss seem half-baked and could use some fleshing out by those who wish to continue with the concept. We should take the warnings from the poor replicability of summer learning loss and the limited usefulness of post-disaster learning loss to heart. This is, of course, the lesson of scholastic alchemy. Policymakers and educators want to help kids learn and recover from the disruptions of COVID. They adapted a measure of summer learning loss (already disputed!) and began trying to spin gold from lead. One of the big responses to learning loss was to implement tutoring but academic results have been mixed and programs are struggling with attendance, including when tutoring was in-person. A seemingly simple problem seemed to have a simple solution, but it never quite panned out, did it?

There’s a reason we do this over and over in education: scholastic alchemy.

I would like to extend this idea beyond the classroom to our entire system of schooling. We’ve seen reform after reform fail to produce the expected outcomes. There are many ways that ideas drawn from politics, economics, various academic research traditions, the media, the public, and so on enter schools and change in unexpected ways. We have cultural idioms about this! No plan survives contact with the enemy (military saying). The best laid schemes o’ Mice an’ Men/Gang aft agley (Robert Burns, poet). Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth (Mike Tyson).

Scholastic Alchemy means unintended consequences, unexpected complications, but also serendipity and happy coincidence. It means the stated purposes of school may differ from the underlying ideologies and theories of action.

Thanks for reading!