- Scholastic Alchemy

- Posts

- I'm Skeptical: Personalized Learning

I'm Skeptical: Personalized Learning

If it's everything, then it's nothing

Welcome to Scholastic Alchemy! I’m James and I write mostly about education. I find it fascinating and at the same time maddening. Scholastic Alchemy is my attempt to make sense of and explain the perpetual oddities around education, as well as to share my thoughts on related topics. On Wednesdays I post a long-ish dive into a topic of my choosing. On Fridays I post some links I’ve encountered that week and some commentary about what I’m sharing. Scholastic Alchemy will remain free for the foreseeable future but if you like my work and want to support me, please consider a paid subscription. If you have objections to Substack as a platform, I maintain a parallel version using BeeHiiv and you can subscribe there.

This is the second in a series of posts I’m writing about my lack of trust in some big ideas influencing education discourse, policy, and curriculum. Last week I wrote about why I was skeptical about learning loss. This week’s topic is the chimera that is personalized learning. Before I go on, however, I want to remind my readers that skepticism is not necessarily the rejection of an idea. Skepticism is better thought of as a need for more information or higher quality information in an attempt to accurately parse what’s actually going on. Skepticism is asking some foundational questions and seeing what answers pop up. The goal of these posts is to highlight my questions and concerns regarding the topic and try to put together a picture of what I think is happening. I suspect that most of these posts will detect a certain amount of truth surrounded by more speculative or contestable details. So keep an open mind and offer feedback in the comments if you’ve got any.

Personalized Learning: What is it?

Personalized learning occupies a similar education space as Bloom’s 2-sigma problem. It’s something of a holy grail or aspirational ideal for many who work on education technologies, write curriculum, or want to reform school policy. The elevator pitch version looks something like this: imagine if every child received the exact instruction they needed whenever they needed it instead of having to move every kid along at the same pace. It has a kind of tautological pleasure to it. Who, after all, wants a kid to learn the wrong thing at the wrong time?

Once this foundation — that every kid needs to encounter content and skills at their own pace — is established, we need a system for operationalizing that goal. Today, that system is most often “AI” and in the recent past it’s been via computerized learning more generally. The algorithm assigns content and requires demonstration of skills and students move onto the next set of content and skills once they demonstrate mastery. However, there is no reason it has to involve any kind of electronics. Teachers could, for example, create a large variety of lesson plans and curriculum content and support students in moving through them at their own pace. They could let students self-direct their learning like we see in Montessori environments, encouraging exploration and curiosity and the leaning into what each student is doing with helpful guidance and additional opportunities. It could be project-based assignments where the teacher assigns an end-goal and students are free to individually find ways to meet that goal.

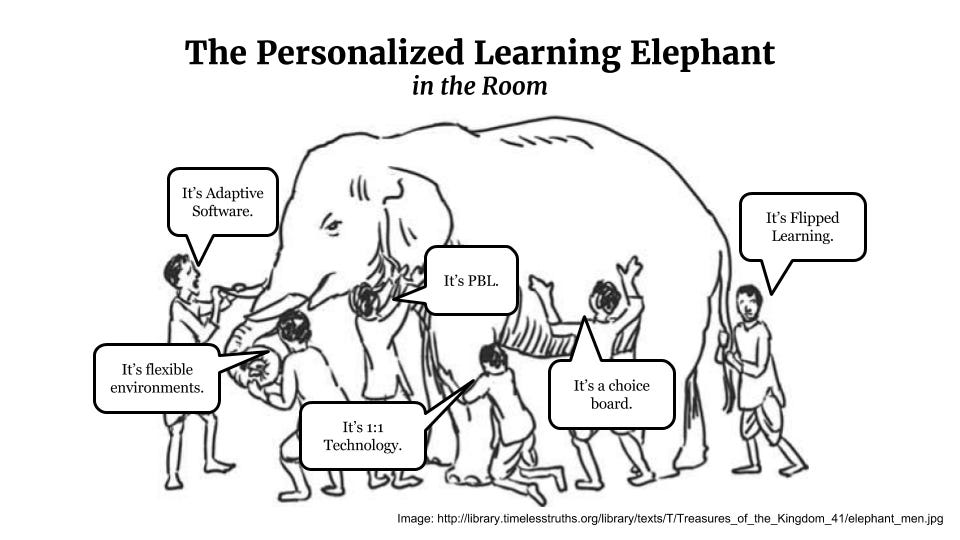

You can see some of the challenge here, though. As you start to look at the many flavors of personalized learning, it becomes hard to nail down what, exactly, personalized learning is and how that differs from just plain old learning. At one time or another, pretty much everything falls under the personalized learning umbrella. Let me put together some examples to illustrate the challenge.

In one math classroom kids are on tablets working through adding and subtracting 3-digit numbers. The software adds complexity to the numbers as kids get more and more questions correct, slowly ramping up the difficulty. The software includes an animated cartoon chatbot that gives kids pointers and praise as they complete their questions.

In another math classroom across the hall, kids are working on a problem set in the back of their textbooks about adding and subtracting 3-digit numbers. The teacher has instructed the students not to move on to the next question until they have gotten the first one correct. She circulates around the room checking kids work, giving pointers, and offering praise as they move on to the progressively more difficult problems.

At the end of the hallway yet another math class is working on adding and subtracting 3-digit numbers. In this class, the teacher has supplied each kid with a variety of colored plastic blocks that can be snapped together in different patterns. In this case the blocks represent the digits of the number. On large sheets of paper around the room, she has arranged a variety of addition and subtraction problems carefully grouped together by their difficulty. Students can choose to start with any set of problems they choose and are to use their blocks to arrive at an answer which they write down and then check with the teacher. The teacher redirects students who get questions wrong to one of the lower difficulty problem sets, having them return after they have mastered the simpler set. Students who get the questions right are directed to the harder problem sets.

All of these fit the idea of personalized learning. Kids are moving at their own pace through a variety of 3-digit addition/subtraction problems and can move to more difficult work as soon as they master the easier work. They get the exact instruction they need at the time they need it. And you can scale these models up or down! The first is just computerized competency-based education. The second is what we think of as traditional schooling. The third is a more project-based method that could follow a competency-based model or flipped model or learning pathway model. Sometimes it feels like literally anything can be called personalized learning which makes it feel like personalized learning isn’t anything at all.

This chimeric quality to personalized learning often means its proponents start to make arguments that sound an awful lot like true personalized learning has never been tried. The better AI or perfect curriculum model or move to mastery-based gradeless education are always just around the corner. That thing over there that you say didn’t work, yeah, that’s because it’s not really personalized learning.

Is Personalized Learning Even Different from Regular School?

Larry Cuban tried to break down what was meant by personalized leaning by visiting dozens of schools in Silicon Valley that purported to be doing personalized learning (he’s a Stanford professor so it was in his back yard). He arrives at the same dilemma I do and offers a helpful illustration of the problem.

the original link is lost to linkrot

Ultimately, he came to the idea of a personalized learning continuum.

At one end of the continuum are teacher-centered lessons within the traditional age-graded school. These classrooms and programs switch back and forth in using phrases such as “competency-based education” and “personalization.” They use new technologies online and in class daily that convey specific content and skills, aligned to Common Core standards–the “what” of teaching and learning–to make children into knowledgeable, skilled, and independent adults who can successfully enter the labor market and become adults who help their communities.

At the other end of the continuum are student-centered classrooms, programs, and schools. These settings often depart from the traditional age-graded school model in using multi-age groupings, asking big questions that cross academic disciplines to combine reading, math, science, and social studies while integrating new technologies regularly in lessons–the “how” of teaching and learning. Such places seek to cultivate student agency wanting children and youth to reach beyond academic and intellectual development to social, physical, and psychological growth.

But, after all these visits and with schools spread from one end of the continuum to the other, Larry isn’t so sure there’s much new about personalized learning. He makes an important first principles point about personalized learning.

Implementation today, as before, of the popular policy innovation called “personalized learning” in all of its ambiguous incarnations in schools and classrooms depends upon teachers adapting lessons to the contexts in which they find themselves and modifying what designers have created. Classroom adaptations mean that the “what” and the “how” of teaching and learning will vary adding further diversity to both definition and practice of PL. And putting “personalized learning” into classroom practice means that there will continue to be hand-to-hand wrestling with issues of testing and accountability.

Yet, and this is a basic point, wherever these classrooms, programs, schools, and districts fall on the continuum of “personalized learning” with their playlists, self-assessment software, and tailored lessons all of them work within the traditional age-graded school structure. No public school in Silicon Valley that I visited departed from that century-old school organization. And that fact is crucial to any “next big thing” for innovations aimed at altering the “what” and “how” of teaching and learning.

I think Larry really gets to the crux of the challenge here. If the whole idea underpinning personalized learning is that kids have to learn at their own pace, follow their own interests, and achieve mastery of skills they choose to pursue, then a more wholesale redesign of schools is required. You can’t say “kids should learn at their own pace” and then have a thing called “5th grade reading standards” or separate standards across grade levels at all. You can’t group kids by age because the number of times they’ve gone around the sun has little to do with their progression toward understanding the US Civil War.

The logical chain of reasoning breaks down whenever put into practice and that should tell us something about the usefulness of the idea to begin with. If true personalized learning has never been tried but people keep trying and failing, then it might be time to try something else?

The Data are…Unhelpful

You may wonder what the research literature looks like on personalized learning. Well, you run into a few problems. Let’s say you bring up Noel Enyedy’s 2014 report on personalized learning in which he reviewed the extant literature and came to the following conclusion: “However, despite the advances in both hardware and software, recent studies show little evidence for the effectiveness of this form of Personalized Instruction.” But that’s 2014! Look at how far things have come since then. We have AI chatbots now! We have computers in the palm of every child! Certainly, these new technological capacities would exceed what was on offer over a decade ago. True personalized learning, it would seem, has never been tried. Enyedy also makes a very familiar point.

This is due in large part to the incredible diversity of systems that are lumped together under the label of Personalized Instruction. Combining such disparate systems into one group has made it nearly impossible to make reasonable claims one way or the other. To further cloud the issue, there are several ways that these systems can be implemented in the classroom. We are just beginning to experiment with and evaluate different implementation models—and the data show that implementation models matter. How a system is integrated into classroom routines and structures strongly mediates the outcomes for students.

Have things improved? Did we use the last decade to come to a better understanding of implementation? Can we make more reasonable clams and support them with evidence? Walkington and Bernacki’s 2020 introduction to a special journal edition on personalized learning suggests the answer is no. They even make the point that researchers are avoiding looking into personalized learning.

The field of personalized learning has arrived at a critical juncture in its development. PL approaches are being broadly implemented in schools, and as implementation spreads, the research base that appraises these approaches needs to mature and change. Researching PL is a daunting undertaking due to complex logistical and theoretical issues, including unclear definitions, variable implementations, and the implicitness of theories of learning. Research efforts are also challenged by the difficulty involved when substantive changes to traditional structures of schooling are attempted: disarray can occur when educational interventions are scaled quickly across classrooms with varying levels of support, buy-in, and resources.

It’s not that there is zero research, it’s that the research is all over the place with dozens of different ideas about what personalized learning is operating all at the same time and being assessed according to highly variable standards. Indeed, the only large-scale study of personalized learning hasn’t published a report since 2015. That report says RAND will produce a more complete report in 2016, but I can’t find it anywhere. Does it exist? I am fairly sure the answer is no. I’m not sure the research has continued. 10 more years should be enough time to get some longitudinal results. Perhaps it was funding? Obama’s signature education initiative, the Every Student Succeeds Act, included funds specifically for states to support personalized learning and that all got cut by Trump and the GOP in 2017.

Bernacki (same one), Lobczowski, and Greene bring us another review of personalized learning in 2022 where we see that the story is still pretty much the same. The link is to the preprint so some stuff is missing, like their figures, but the published version is paywalled at Educational Psychology Review. In this review, they have all but given up on trying to evaluate the impact of personalized learning on learners.

At present, the research base on personalized learning is beset by the complexity induced by policies that promote implementations that are free to vary the number and types of components they involve to personalize a learning experience. Any attempt to summarize the effect of personalized learning on the learner experience, learning process, or academic performance achieved is thus at risk of inducing a jingle jangle fallacy (Gonzalez, MacKinnon, & Muniz, 2020) where many different types of personalized instruction are conflated under a single, insufficiently precise label of personalized learning. As a result, educators who wish to derive these perceived benefits for their students may adopt an instantiation of personalized learning that bears similarity in name, but varies in its implementation from past programs, and thus fails to confer promised benefits to students.

The emphasis there is mine. It’s amazing to me that this is written in a published article. Personalized learning has the word learning in the name, but we can’t tell you if it has anything to do with learning so we’re not going to try. Instead, they write a systematic literature review to answer three other questions:

We identified 376 unique studies that investigated one or more PL design features and appraised this corpus to determine (1) who studies personalized learning, (2) with whom, and in what contexts, and (3) with focus on what learner characteristics, instructional design approaches, and learning outcomes.

That statement about learning outcomes, by the way, is not them looking at the outcomes systematically and seeing what was learned. No, the reviewers only wanted to know what outcomes the original studies were interested in. They do not report on the actual outcomes, measure effect sizes, or do any kind of analysis to determine if the personalized learning in these 376 unique studies, you know, leads to learning.

Personalized Learning: It’s Scholastic Alchemy

So, there you have it. Pretty much anything you want can be called personalized learning and the field is so messy that the people trying to get some sense of whether or not personalized learning helps kids learn have given up. Yet, we still see people forging ahead with personalized learning and presenting it as a panacea, especially because AI will finally make true personalized learning possible. Just like the alchemists of old, our schools will be expected to turn personalized learning lead into actual learning gold. I remain skeptical.