- Scholastic Alchemy

- Posts

- I'm Skeptical: Science of Reading

I'm Skeptical: Science of Reading

Sometimes even those wary of being sold a story are still being sold a story

Welcome to Scholastic Alchemy! I’m James and I write mostly about education. I find it fascinating and at the same time maddening. Scholastic Alchemy is my attempt to make sense of and explain the perpetual oddities around education, as well as to share my thoughts on related topics. On Wednesdays I post a long-ish dive into a topic of my choosing. On Fridays I post some links I’ve encountered that week and some commentary about what I’m sharing. Scholastic Alchemy will remain free for the foreseeable future but if you like my work and want to support me, please consider a paid subscription. If you have objections to Substack as a platform, I maintain a parallel version using BeeHiiv and you can subscribe there.

This is going to be a long post. Like more than 8000 words. It will not fit in your email. Sorry. It’s necessary.

Requisite Throat Clearing

If any post of the I’m Skeptical series has a chance of blowing up in my face, I’d argue this is the one. The Science of Reading inflames passionate feelings, especially among its most ardent advocates. My skepticism is not that the science of reading is wrong but that the Science of Reading is misleading. Note the capitalization here. What was once a movement among the parents of students with reading disabilities is now a nationwide brand and, as such, has taken on a life of its own, often bearing little resemblance to the actual science underpinning the science of reading. (Ain’t that the essence of Scholastic Alchemy?) The advocacy around the Science of Reading has become so stringent, however, that I think it’s necessary to demonstrate that I am, in fact, a fan of following evidence-based reading practices and believe every elementary reading curriculum should include structured phonics instruction beginning with the English alphabet, phonemic awareness, and phonics. These are, I think, well established in research and should be the foundation of any child’s schooling. Saying that doesn’t mean I endorse any specific curriculum, and I find myself worried that what is actually happening in schools is more the product of marketing, branding, and quick-fix mentalities than evidence-based instruction.

My background with the science of reading is reasonably extensive albeit somewhat self-taught. My journey with the science of reading started as a high school teacher who encountered students in need of foundational literacy instruction. None of my high school teacher prep focused on foundational skills because, why would it? 14-year-olds are expected to know how to read when they arrive. In high school we are supposed to be working on advanced comprehension, knowledge building, and writing. Yet, some students, even a few without IEPs or diagnosed special needs, struggled to read basic written text and failed to write even simple sentences. This population became my focus and after my first year at the urging of our school’s SLP, I homebrewed a deep dive into foundational reading instruction. I became Orton-Gillingham certified, using my own money with no reimbursement for the training. I purchased (again, with my own meager teacher pay and no reimbursement) manuals and materials for Tier 1 and 2 of the Wilson Reading System as well as WADE and WIST handbooks. I joined the SpellTalk listserv, the underground dark matter powering the Science of Reading movement in 2009. There, I asked many questions and learned much. I am still reading the listserv to this day. I read up on Chall and Ehri and Gough. This led me to manuals for the diagnostic teaching of reading, textbooks about the psychology of reading, and to purchasing both Tier 1 and 2 instructional sets for Spell Links. Looking at my shelf, I also have Tier 3 manuals but I have no memory of buying these or using them. Goes to show you, I may have overdone it.

I probably spent more than $2000 that summer gathering resources and completing training. Why? My goal was to create a course for struggling readers who entered high school far behind their peers in reading ability. Initially, I crammed foundational reading instruction into my regular 9th grade ELA curriculum, targeting students who needed that additional support, but my plans really took shape with the support of my department chair and the vice principal supervising my department. The following year, we used a holistic approach to identify rising 8th graders who needed help. The basic version was we used 5 measures that either gave 1 point or 0 points. If their ELA state test scores were below the passing threshold, 0. If they had a failing grade in ELA at any point in middle school, 0. If they were chronically absent in any year of 6-8th grade, 0. If they spent more than 10 days in suspension, 0. If they were in special education and had a disability related to their reading performance, 0. Any kid scoring 3 or lower was placed into an elective class, initially a study hall period. We tested them during the first week of high school, before schedules were finalized, and any who tested as needing foundational literacy support stayed in that study hall for the year. The others were free to take regular electives. And so, for a whole year, there were two study hall classes of about 20 kids each receiving instruction following what we now call the science of reading (that branding didn’t really pop off until the late 2010s). I taught one, the school’s SLP taught the other (we were lucky she was also certified to teach and not just do speech therapy).

This intervention worked well and when junior year rolled around all of the students passed their high school graduation tests in reading and writing. Not only that, but we saw improved grades across the board as students were better able to access the curriculum in their other classes and improved behavior because kids who can’t do the work often act out and become disruptive. Notably, large scale studies of programs similar to mine showed promise for improving high school students’ literacy. Later on, after I got married and followed my wife around for medical school and then residency, I went back to school and got a Literacy Specialist master’s. While I didn’t learn all that much new about teaching reading (I knew quite a bit already by that point), I did learn quite a bit more about how to write curriculum and take on instructional support roles. This let me work in elementary and middle schools supporting reading instruction for a bit before going back yet again for a doctorate.

I don’t like to tout my credentials. This may be the first time I’ve mentioned my doctorate on this Substack. To me, what I write should not rely on some position of authority I may have printed on a sheet of paper. My writing here should be credible because I have persuasive argument, share evidence to support it, and draw on relevant experience that others can recognize. So, please believe me when I say that I understand the value in teaching phonemes, phonemic awareness, and phonics and that I believe the preponderance of the evidence supports foundational literacy instruction following the science of reading. I’ve seen it work! It should also say something about the current zeitgeist related to the Science of Reading that I feel it is necessary to spend 1000 words clarifying my stance and my support. I am, however, skeptical of the constellation of curricula, parents’ rights movements, and political polarization surrounding the Science of Reading (from here on out this is going to just be SoR).

American annals of education and instruction, 1836 upped the contrast to make text clearer, the first official use of the science of reading

The Science of Reading is not the science of reading, hence my skepticism

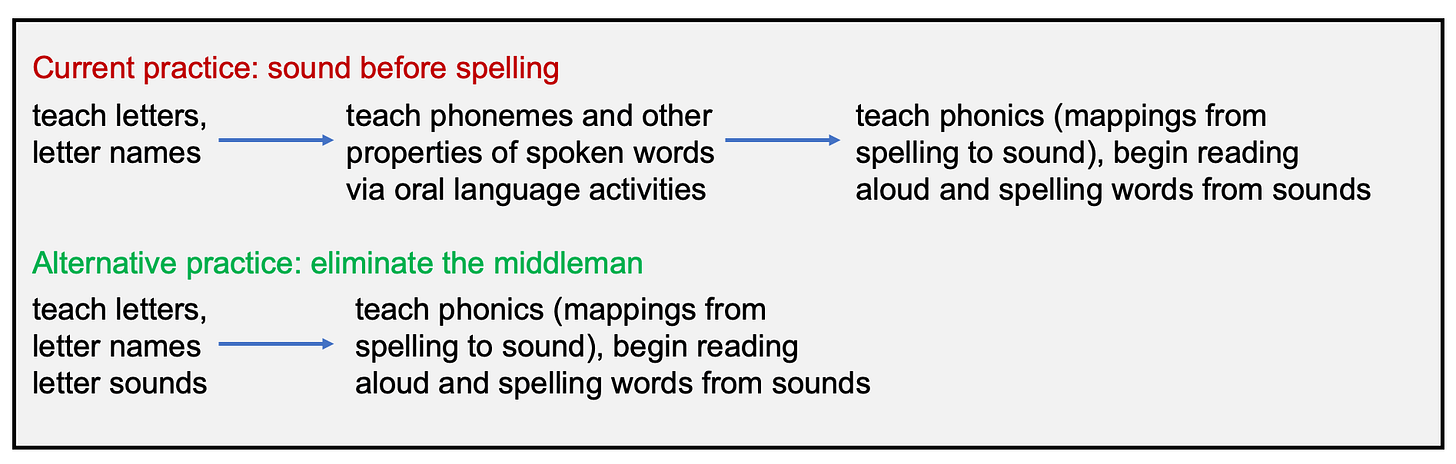

A microcosm of the gap between SoR and the science of reading can be found in ongoing disputations about how readers achieve phonemic awareness. Phonemic awareness is the ability to connect the idea of a letter to the sound that letter makes and multiple letter sounds into whole words. Phonics is the next “step” which is what most people are more familiar with and is when readers connect multiple letters and their sounds together into words, on paper, and in printed text. There is a surprisingly lively gap between practitioners of SoR and the scientific literature underpinning our understanding of the science of reading.

The practitioners want classroom facing instruction to feature explicit instruction in the phonemes of the English language. This often looks like students and teachers doing call-and-response work across all 44 phonemes we use in English. Beyond that, the curriculum may require students master those phonemes and other more advanced concepts like substitution or phoneme deletion. There may be flash cards or big charts, adapted from therapeutic approaches for children with disabilities, kids follow along with as they memorize each one. The idea here is that phonemic awareness is a precondition for learning to read. Without knowing all of this, they argue, kids can’t begin the process of reading whole words. Explicit instruction in phonemic awareness is teaching kids about a property of words in the English language, that the word CAT is composed of the individual phonemes for /k/, /a/, and /t/.

The problem is, researchers disagree that this is actually a property of language and especially disagree that this is how our brains process language cognitively. What they point out is that segmenting words into phonemes like /k/ /a/ /t/ is a method developed by linguists to describe the sounds of speech. It is not a property of the language itself. Phonemes are not units of spoken words. Mark Seidenberg, a computational linguistics researcher and proponent of the science of reading, has made this point clearly using the example of the word BAT. He argues that

[t]he initial hurdle is grasping the alphabetic principle, whereby units in the written code (graphemes) represent units in the spoken language (phonemes). Several potential obstacles arise. First, as I’ve already noted, phonemes are an abstraction that depends in part on exposure to print.

Researchers like Seidenberg do not think classrooms of students need to be doing rote memorization of phonemes and their principles. They are, at best a middleman on the way to actually reading print and at worst a waste of time because students are learning descriptive linguistics used by academic researchers instead of how to read. What teachers should be doing with their students is going directly from the alphabetic principle to letter and word sounds. Moreover, it could even lead to confusion as written text is brough into the mix and sometimes fails to adequately resemble the phonemes learned previously. Phonemic awareness is better thought of as a product of learning the alphabetic principle and its sounds rather than as a discrete step.

source

Yet, practitioners disagree. They want systematic approaches to include this kind of explicit step, even if it does not represent how language works and I am unsure why this is the case. Presumably, the Science of Reading would follow along with scientific approaches to how reading works, especially the critical early stages of reading development. Moreover, practitioners should be acutely aware that time in the classroom is limited and spending time on unnecessary extra instruction carries a cost. Yet, SpellTalk regularly has threads going into the hundreds of comments with practitioners objecting to researchers attempts to press for more accurate curricula. (I can’t reproduce these here because it’s against the listserv’s TOS unless I go get everyone’s permissions individually, apologies). This disagreement is only one small dispute. Much bigger problems show up once kids are moving beyond the need to learn phonics.

The Science of Reading: SPED for all

One reason I suspect that teachers and literacy specialists are attached to explicit phonemic awareness instruction and adhere with fidelity to other aspects of the SoR curriculum is that this is what they have received from the originators of the Science of Reading. The instructional materials and practices commonly called the Science of Reading and used in elementary classrooms come from speech therapists and language pathologists who utilize clinical diagnostic tools and therapies for students with disabilities in order to teach them how to read. If a student has a specific learning disability that prevents her from learning to read, such as dyslexia, a speech and language pathologist will include explicit phonemic awareness instruction as part of the therapy. Orton-Gillingham and WRS are systems initially developed as clinical tools for therapists, not as classroom instruction. You could look at something like Amplify, where they champion how their products are entirely driven by the science of reading, and miss in the detail that they are “the only digital provider of DIBELS 8th edition assessments, provides universal screening, dyslexia screening and progress monitoring to assess your students on their reading trajectory and what skills they need to develop.” This is a special education therapeutic program being marketed to schools as useful for every kid learning to read.

When teachers, including me, went looking for ways to incorporate foundational reading instruction into their classrooms, explicit phonemic awareness instruction was part of what they found. When curriculum publishers went looking for materials and practices to put into SoR aligned elementary reading curricula, phonemic awareness therapies were part of what they found. What I find interesting, though, is that nobody really mentions this origin story when they promote SoR for general classroom instruction. It’s almost as if they don’t want to say that they’re recommending every child in the class receive special education reading instruction. Maybe they should! I don’t think it is inherently harmful to the students who are ahead, and teachers can always differentiate a bit if needed. There are other areas of teaching and learning that developed first in special education capacities and then moved into general classrooms (e.g. Reciprocal Teaching).

The whole question is one of opportunity cost, of innovating and altering the curriculum beyond what was received and of parental acceptance of the curriculum. My skepticism comes from the sense that schools, teachers, and other practitioners are not free to innovate or alter the curriculum they received from special education and that there is a growing dogma within the SoR community, as evidenced by their objections to questions about how to best deal with phonemic awareness, comprehension, fluency, and knowledge-building. My skepticism comes from the sense that advocates don’t want to tell parents that the SoR their kids are getting comes from interventions for special education students.

Comprehension seems beyond SoR

You might presume that any curriculum purporting to teach reading would teach all aspects of reading, but SoR curricula often focus almost exclusively on early grades foundational skills to the detriment of comprehension, vocabulary, and knowledge-building. Experts and researchers are starting to notice this problem and argue that, while

[p]rogress has been made in the science of reading simple texts, now progress is needed in developing students’ ability to read and understand difficult science, math, and English language art texts which requires building up students’ vocabulary and background knowledge.

Others are noticing that there is simply not enough time devoted to proper reading comprehension instruction, especially in upper elementary school. Yet, we hear from SoR advocates that comprehension is simply not part of the science of reading. We should stop at the Simple View of Reading (itself a misreading of Gough & Turner) and treat kids who can properly say words on a page as though they understand words on a page. It is doubly surprising because the simple view of reading is half language comprehension!

the simple view of reading

They tell us that what matters most is word recognition and share with us proprietary research findings from the curriculum publisher to support the claim.

Haskins Lab “at Yale” apparently never published this study anywhere but the curriculum’s website.

So, yeah, if 89% of reading is simply being able to recognize the words on the page. It stands to reason that the other 11% must be comprehension, knowledge, and vocabulary. Small potatoes compared with word recognition. Yes, I get that’s not what that 0.89 is referring to, but this is how it’s interpreted by SoR advocates who dismiss the need for anything other than word recognition instruction, e.g. phonics. While I have no idea which study or data from the Haskins Lab this graph comes from, I do have other actually published work from a researcher at the Haskins Lab that says something different. To wit:

These findings present evidence that adults’ higher-level reading skills (comprehension and vocabulary) are partially dissociated from lower-level skills (spelling and decoding). This finding is consistent with Jackson (2005), Lundquist (under review), and Perfetti and Hart (2001). Moreover, print exposure clustered with higher-level skills, suggesting a strong relationship between experience and comprehension ability.

Finally, the regression analyses suggest that decoding accounts for only a very small amount of the variance in comprehension ability (\1%) in this sample of adults, even when decoding is entered before higher-level skills. This result differs somewhat from that of Braze et al. (2007) who found decoding to be a moderate predictor (accounting for 11%) of the variance before vocabulary was entered into the equation and a weak predictor (accounting for *1%) after entering in vocabulary. One difference between the current study and theirs is that they specifically sought out participants that were likely to have poor literacy skills (most from community colleges) and the current population attended a traditional university. Moreover, this finding is also different from findings with young children who have reading difficulty (e.g., Shankweiler et al., 1999), that have identified a very high correlation (.79) between decoding and comprehension. This difference is consistent with the hypothesis that decoding has a larger impact on comprehension ability when overall reading ability is low (Bell & Perfetti, 1994).

Now, this is a study of adults and Landi does make the point at the end here that decoding (that’s the ability to use phonics principles to be able to say new words) matters more for people with low reading ability. Kids learning to read are, by definition, people with low reading ability. What’s the big problem, you may be thinking, with the focus on phonics and other foundational skills? The problem is not the focus when they’re learning to decode. It’s that there’s no sense that follow-up with comprehension instruction is just as, if not more important. Yet, obviously, when they’re all grown up adults, the stuff that is going to make them literate readers is higher-level skills and experience. As Landi puts it: “Furthermore, follow-up regression analyses showed that the high-level sub-skills (e.g., vocabulary and print exposure) were significantly better predictors of reading comprehension ability than the low-level skills (e.g., decoding and spelling) in adult skilled readers.”

What is the purpose of teaching reading? Is it to make kids into good 3rd grade decoders or is it to make kids into literate adult readers? From what I’ve seen of SoR, it really seems like they care more, almost exclusively, about the former.

Science of Reading has failed in the recent past

When you hear about SoR, you often hear that the best, highest quality scientific evidence was being ignored or suppressed in favor of more marketable or politically connected approaches, such as Lucy Calkins’ Units of Study. You might get the impressions that schools in the US have never really tried to teach kids to read in a way that aligns with the science of reading or with the Science of Reading. But that’s not true. In fact, there has been a recent large scale and well-funded push for scientifically backed reading instruction: Reading First. Indeed, Reading First, a $1 billion-dollar program to support schools’ adoption of evidence-based literacy instruction, may have been the only effective component of No Child Left Behind.

The Reading First program used a rigorous application and review process to distribute over $900 million during a five-year period to state and local education agencies for use in low-performing schools with well-conceived plans for improving the quality of reading instruction. The federal funding had to be applied to reading curricula and teacher professional development activities that are consistent with scientifically-based reading research — that is, that incorporate the five critical building blocks of effective reading instruction (phonemic awareness, decoding/word attack, reading fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension). Once approved for funding, schools were expected to: (1) ensure that research-based reading programs and materials are used to teach students in K-3, (2) increase access and quality of professional development of all teachers who teach K-3 students, to ensure that they have effective skills for teaching reading, and (3) help prepare classroom teachers to screen, identify, and overcome barriers to students’ ability to read on grade level by the end of third grade.

How’d that go?

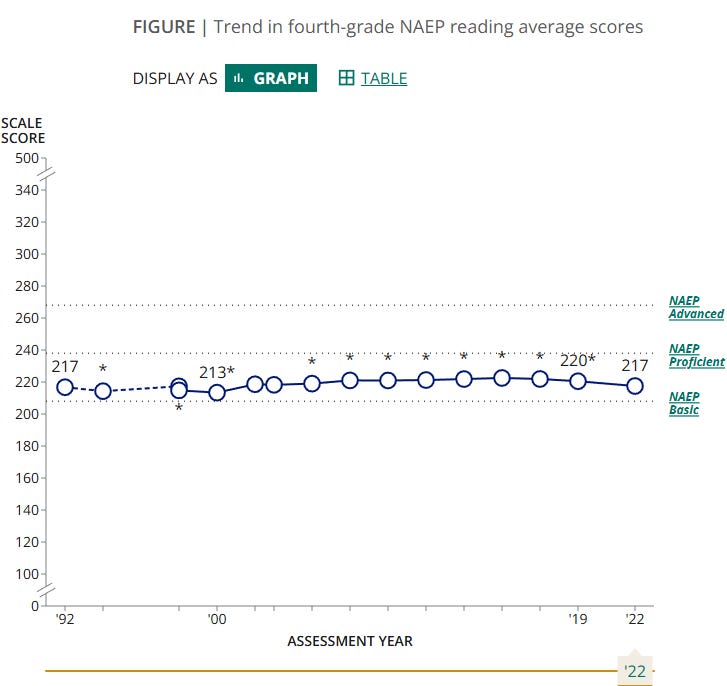

I guess we can call that a slight bump in ‘04-’05 and then flat until the 2019 NAEP. If you look at the final report, however, the outcomes are murkier.

The results indicate that Reading First produced statistically significant positive impacts on multiple reading practices promoted by the program, such as the amount of instructional time spent on the five essential components of reading instruction and professional development in scientifically based reading instruction. Reading First did not produce a statistically significant impact on student reading comprehension test scores in grades one, two or three. However, there was a positive and statistically significant impact on first grade students' decoding skills in spring 2007.

We paid schools to implement the science of reading, they did, and all we could really prove was that schools did indeed do more instruction based on the science of reading. Somehow, though, Emily Hanford and others present us with a story that “[t]here's an idea about how children learn to read that's held sway in schools for more than a generation — even though it was proven wrong by cognitive scientists decades ago.” Given that Reading First went defunct in 2008, this statement seems inaccurate! There’s even an episode of the podcast dedicated to Reading First which presents the failure of the program as a political shutdown, something pressed for by Democrats angry that some members of the Bush administration had financial connections to curriculum companies recommended by the program and actions by Marie Clay to get the program shut down because her reading curriculum was not included. Corruption aside, I think it’s important that the impact study itself finds the program ineffective. The impact report, the fact that Reading First did not produce a statistically significant impact on student reading comprehension, is not mentioned in the podcase episode about Reading First. Given the depth and breadth of the reporting Emily Hanford did for this series, I can only assume the impact study was omitted because it did not support the overall argument in favor of the Science of Reading that she is trying to advance. (See also Gamse et al., 2008; Jackson et al., 2007. I don’t have easily linkable versions of these articles, but I’ll try to remember to go looking. They’re citations I have on hand from other things I’ve written.)

This matters! Sold a Story is probably the piece of journalism with the most impact on education in forty years. Science doesn’t omit conflicting information because it is inconvenient. Advocates got what they wanted. Kids did more decoding and more phonemic awareness and did better at those things, but it didn’t matter in the long run because comprehension depends on more than just the ability to use phonics to decode words. That should be a data point incorporated into discussions of the science of reading, broadening and advancing what advocates seek to see implemented in schools.

I’m not the only SoR skeptic

It might feel like I’m pulling a Charlie Day and stringing together a bunch of objections that misrepresent or misjudge the Science of Reading. I’m not.

This is not what I look like right now!

Last year a pair of reading research heavyweights with decades of experience and credibility within the reading research community took it upon themselves to Fact Check the Science of Reading. They evaluated the evidentiary basis of ten claims made by proponents of the Science of Reading. I’ll put those claims below along with lengthy sections from their evaluation. But don’t take my word for it, read the full report for yourself! It’s a lot, I know.

Explicit systematic phonics instruction is the key curricular component in teaching beginning reading.

A close examination of these reports, informed by the research syntheses and various meta-analyses we have just reviewed, reveals them to be generally in favor of phonics—again, not on its own, but as a key component in a more comprehensive curriculum. These are certainly more modest than the claims made in the media, blogs and other outlets by policy advocates (e.g., Buckingham, Wheldall, & Beaman-Wheldall, 2013; Hanford, 2018; Moats, 2000).

Looked at historically, the characterization of phonics—as a) exerting a greater effect on reading words and/or pseudowords than understanding text and b) one key piece in a larger and broader curriculum—is consistent with the cautions offered in a long line of efforts to determine the best method for teaching reading.

The Simple View of Reading provides an adequate theoretical account of skilled reading.

Many of the sympathetic reading researchers who extol the SVR—and readily refer to the 150+ studies validating it—have also been conducting research to evaluate and revise the model; in short, to improve it! Most of these endeavors attempt to add complexity within the SVR’s current parameters, such as incorporating new features within the Decoding and Language Comprehension buckets. Some have also attempted to replace the model with a more complex alternative

While we can live (and indeed, have lived) with the SVR, we believe there are no credible theoretical, empirical, or practical reasons for making do with an adequate model. That is, we see no compelling ideas, research findings, or implications from those findings regarding classroom teaching that require us to put square pegs in round holes, especially when we have a more fulsome model (a sociocultural view of reading) available. We will unpack this framework in our treatment of Claim 9.

Reading is the ability to identify and understand words that are part of one’s oral language repertoire.

Over the years, scholars have brought different assumptions and goals to the debate—leading to incommensurable definitions of reading and complicating, if not dooming, conversations across perspectives. According to Rayner et al. (2001), the distinctive essence of reading is the process of decoding print to speech. As such, their definition intentionally excludes passage-level (connected discourse) factors—along with the social, cultural, and contextual resources available to all readers. The Alexander and NAEP definitions, on the other hand, attempt to move beyond decoding—emphasizing instead the social, cultural, and functional applications of reading, such as inquiry, knowledge acquisition, or perhaps even action, in real world settings. This also has implications for instruction: For instance, notice how easy it is to leap from the Rayner et al. definition to a pedagogical emphasis on cracking the code. By contrast, see how easy it is to leap from the Alexander or NAEP definitions to a comprehensive approach that attends to the contexts, functions, and applications of reading to learning or problem-solving. It should not be underemphasized that Rayner and his colleagues limited what counts as reading to the naming of words and the understanding of their decontextualized meanings. Not phrases, sentences, discourse, or genres, but words. In the definition proposed by Rayer et al. (2001), the understanding of units larger than words is not a part of “reading”—so it must 48 Claim 3 be accomplished by knowledge and processes that are a part of literacy. Hence, larger units arise in functional situations (real world contexts) in which we learn to read worlds, including texts that describe those worlds. In short, the Rayner et al. (2001) focus on word naming comes at a conceptual cost—assigning all things social, cultural, contextual, epistemological, and motivational to literacy and learning. For our part, we would rather keep them front and center within the construct of reading!

What counts as reading? This remains a key question at the center of the SoR debate. If reading is defined as identifying and understanding words that are a part of one’s spoken language, then it makes sense to focus on what many novices lack when they enter school (i.e., the cipher that maps print to speech, acquired through systematic decoding instruction). However, if reading is defined more broadly, then it makes sense to offer a comprehensive curriculum that orchestrates those many processes and types of knowledge—in terms of the code; word meanings and relationships; language; and (perhaps most important) the social and cultural worlds in which we use reading, writing, and language to make sense of things. With such disparate perspectives, it is little wonder, then, that our debates are seldom resolved. Nowhere is this tension between competing definitions more active than in the models of the reading process, including models of how it develops (as noted in Claim 2, concerning the adequacy of the SVR).

Phonics facilitates the increasingly automatic identification of unfamiliar words.

We have no quarrel with this formulation of the development of expert, efficient reading. We accept the idea (and the research supporting it) that expert readers develop (i.e., over time and with appropriate experiences, pedagogy, and exposure to texts) a large portfolio of immediately identifiable and understandable words (i.e., words whose pronunciations and meanings are readily available for meaning making). We do, however, quarrel with the pedagogical recommendations that accompany the underlying theory and research of reading development. Our quarrel is largely empirical rather than theoretical, focusing on the evidence that runs counter to the claims in the pedagogical implications.

We have mixed views on the acceptability of this claim. The act of reading for meaning may or may not entail word-by-word reading, especially if the reader is engaged in reading for meaning (e.g., engaging in visualizing, inferencing, etc.). In other words, an emphasis upon word-by-word reading may not support a reader’s enlistment of an array of comprehension processes, important over time, for reading for meaning.

The Three-Cuing System (Orthography, Semantics, and Syntax) has been soundly discredited.

The only way we can make sense of the arguments marshalled against the three-cueing system is to infer that the opponents object to its use in pedagogy rather than in reading theory. Many of the most vocal critics of the three-cueing system either espouse or support models of the expert reading process that posit an important role for all three of these information sources. They describe how readers recognize and understand words and connected discourse through the combined processing mechanisms for orthographic information, semantic information, and syntactic information (as well as other sources, like letter features).

In our view, however, SoR advocates have been too quick to dismiss the positive contributions of multiple cueing models and approaches— namely, that they support word identification and understanding, as well as the development of word learning, word solving, and orthographic mapping. Reading requires an orchestration of various factors across words and sentences. It seems overly limiting to discredit the use of cueing systems based on what some might consider a restrictive assumption—that reading is entirely the accurate naming of words, rather than an act of meaning making that involves hypothesizing. To dismiss the use of context as an over-reliance on “guessing” or “predicting” ignores important evidence. The essence of most theoretical models of reading involves semantic, syntactic, and orthographic processing. We also find some of the arguments against cueing systems (i.e., the view that the use of context or syntactic, semantic or pragmatic cues, even when coupled with phonics, may detract from word learning) to require the out of hand dismissal of important lines of research. Opponents of cueing systems fail to consider research that might counter their position. They suggest the need for, but sometimes fail to examine, studies considering these matters more directly with students as they learn to read. And, despite the danger of extrapolating from comparisons of good and poor readers, they use those studies to support their critique of an emphasis on context or the use of cueing systems (Seidenberg, 2017).

Learning to read is an unnatural act.

As noted, some who argue that learning to read is unnatural also acknowledge that this is not universal to all learners (e.g., Castles, Rastle & Nation, 2018; Seidenberg, 2017). They recognize that exceptions exist; indeed, they do not exclude the possibility that some beginning readers and writers draw upon something akin to a natural prowess for discerning, applying, and refining reading and writing skills.

Our own sentiments align with those of both Bruner and Meek. We don’t propose a wired in reading acquisition device that parallels the consensus view of a built-in language acquisition device (Chomsky, 1965). However, we do believe that all humans are wired to engage in sense-making in all their encounters with the natural, social, and cultural worlds in which they live. They seek coherence in their explanations of everything. From this perspective, learning to read is no more or less natural than learning how to cross a street, ride a bike, do multiplication, categorize dinosaurs, or find support for claims you make when developing arguments.

Balanced Literacy and/or Whole Language is responsible for the low or falling NAEP scores we have witnessed in the US in the past decade.

Can and should such test results be used to support causal connections between past and present practices and outcomes—especially if the timelines for practices and the results do not always align? We concur with a number of our colleagues: The use of national and international test results to judge the effectiveness of approaches to teaching reading constitute a commonplace problem. As Bowers (2020) argued, it is a bridge too far for a government to attribute improvement in national and international test results to their advocacy and demands for phonics instruction—or, for that matter, for any type of instruction. These claims often draw faulty inferences about patterns and trends in test scores; misinterpret performance levels (e.g., basic versus proficient versus advanced); and ignore the correlational nature of the evidence. These arguments also ignore the limits of the measures themselves. Even if we did accept the dubious practice of elevating correlations to causal connections between practices and outcomes, we would be forced to also acknowledge that on other outcomes—such as the enjoyment of reading—the evidence favors those countries that have been largely spared from reforms and mandates requiring the teaching of phonics (Goldstein, 2023).

We do not deny that there should be an increased investment in reading instruction; however, it should not be based on claims that dismiss past efforts and suggest new directions without stronger evidence. Aligning the timing of educational developments with test performance data is quite speculative; it is well-nigh impossible to ascribe causality with any confidence. At best, such data provide a justification for probing more deeply, by conducting experimental research that can evaluate the causal relationships between programs and outcomes. Moreover, this practice ignores (perhaps conveniently) those economic and other factors have been shown to be influential. Yet in the United States and elsewhere, educators, the public, and politicians and policy makers continue to be presented with such evidence to support or dismiss educational developments.

[Bonus Debunking] A recent manifestation of this tendency involves the heralding of developments in Mississippi. The alleged Mississippi Miracle—celebrated by the governor of Mississippi, The Washington Post, and the National Council on Teacher Quality (NCTQ)—was touted as an example of how phonics instruction would lead to dramatic NAEP score increases. Unfortunately, closer examinations of the data and Mississippi education policy have raised concerns that the data may not be as strong as claimed (especially over the long term). The alleged increases in reading performances may have arisen not from an emphasis upon phonics, but rather from policies directed at teaching to the test and from the exclusion of certain students from being tested. Indeed, further examinations expose what might be considered more tempered claims for improvements in reading performance, as well as uncertainly about the antecedents of such results—questioning the influence of the shift to phonics, and the extent to which such initiatives are replicable (Drum, 2023; Westall & Cummings, 2023). In reviewing the Mississippi results, LA Times business columnist Michael Hiltzik (2023) and education bloggers Bob Somerby (2023) and Kevin Drum (2023) reported what they deem to be a statistical illusion—one that mischaracterizes Mississippi fourth-grade students’ unprecedented growth in reading performance as correlated with the state’s emphasis on phonics (and, by extension, the Governor’s support of Mississippi’s Literacy Promotion Act). According to Somerby and Drum, the results are not just suspect; they represent a cover-up. The miracle growth suggested in the results, they assert, arises from the exclusion of the lowest 10% of students from the data.

Evidence from neuroscience research substantiates the efficacy of phonics-first instruction.

Given the questionable reliability of such results and other factors that might be in play, claims that enlist select neuroscience studies to argue for the primacy of phonics may be difficult to substantiate or even verify. For example, as Compton-Lilly et al. (2023) report, reading processes involve multiple networks distributed across various regions of the brain (see Table 6); as such, phonics is not exceptional, but one of many information sources and factors related to reading that have been shown to register brain activity. Additionally, at a base level, fMRIs or brain scans have been shown to lack reliability (e.g., when the same stimuli mimicking the same conditions yield different results). Therefore, to match the results from neuroscience to propositions for the primary role of phonics for functional purposes seems spurious—more curious than convincing.

Neurologist and linguist Stephen Strauss (2014) noted that the select findings of by some phonics advocates fail to reckon with the limitations of extrapolating from brain imaging studies… At the very least, and until more definitive neurological (and pedagogical!) evidence is available, we should be somewhat skeptical about connections drawn between the biology of the brain and learning to read. Studies of the brain may not provide evidence of a clear relationship between phonics and learning to read or, by extension, overcoming reading difficulties… In exploring the use of neuroscience in discussions of the Science of Reading, Yaden, Reinking and Smagorinsky (2021) raised some of these same issues. As they note, detractors of neuroscience in the SoR debates have expressed major concerns, including: 1) The extent to which fMRI’s yield images can or should be viewed as discrete images of learning responses associated with teaching specific foundational skills (i.e., apart from other responses to reading); 2) The reliability of such research, especially considering the difficulty replicating data from brain scans; and 3) The extent to which data from brain scans can serve as evidence or the basis for educational practices.

Sociocultural dimensions of reading literacy are not crucial to explain either reading expertise or its development.

It is difficult to understand how the Rayner et al. definition could possibly meet this new standard—defining learning, including learning to read, as an inherently social, cultural, and contextual process. Addressing inequities, especially the needs of struggling readers, is sometimes declared as the raison d’être for SoR approaches to reading. Yet by giving so little consideration to sociocultural factors, such views lead to universal generalizations (i.e., across ethnic groups) and standardized recommendations for instruction. As we have argued, advocates of a narrow definition of reading prefer to keep sociocultural elements at bay—whether it be the situated nature of learning and cognition, consideration of issues of diversity and multiculturalism, or the dynamics of classrooms themselves—and out of the reading process.

In keeping with these perspectives, we think both the evidence about learning, including learning to read (e.g., Lee, 2020; NASEM, 2018), as well as the moral imperative to ensure curricular and pedagogical equity and relevance, point us toward sociocultural views of reading research, theory, and practice. The mistake, we think, of the SoR reform initiatives is that in their zeal to ensure a secure hold on the science of word reading and understanding, they have lost their grip on the other equally-scientific endeavors—namely, the vast body of research that tells us that learning is enhanced when matters of diversity, equity, relevance, ecological validity, and cultural plurality are front and center in our enactment of curriculum and teaching. Time to rebalance!

Teacher education programs are not preparing teachers in the Science of Reading.

Our reading of the claim and evidence leads us to conclude that the research used as the basis for evaluating teacher education programs fails to meet the standards for evidence-based practice that such arguments claim to support. The critiques coming from NCTQ and other sources (e.g., Moats, 2014; Hanford, 2019; Seidenberg, 2013) attempt to link teachers’ knowledge of effective practices and the linguistic principles behind those practices to classroom practices; they further assume that what teacher education students do once they get into their own classroom is a direct reflection of the influence of the teacher preparation programs that they experience. A further assumption behind the NCTQ critique (and many prior critiques) is that if teachers can receive the right, relevant technical knowledge, they will more or less automatically apply related and implied research-based practices effectively in their classrooms.

If the NCTQ scholars, or scholars who align themselves with some version of the SoR, want to use teacher education, either pre- or in-service, as a vehicle for promoting enduring changes in classroom practice, they need to contextualize their policy efforts and research syntheses in a more substantive understanding of the rich lines of theory and research on teacher education, teacher learning, and teacher change. Implicit in their recommendations seems to be erroneous theory of action, which assumes that (a) if you provide teachers with the right knowledge and (b) provide incentives and/or sanctions for holding themselves and their students to practices emanating from that knowledge, change will happen. Teacher learning, teacher change, and teacher education are a lot more complicated than that (Cochran-Smith & Reagan, 2021, 2022; Darling-Hammond & Bransford, 2005).

Okay, I get that I just unloaded a lot on you, but the actual report is 188 pages so I’ve actually saved you quite a bit of time! Either way, it’s really not looking great for the Science of Reading as opposed to the science of reading. As Tierney and Pearson put it, “the Science of Reading is not the whole story”. Unfortunately, schools nationwide are forging ahead on curricula built on the marketing and the branding of the movement instead of on the research base from which its most important lessons and limitations are drawn. We are expecting, more or less, a miracle to come from teaching phonics but what we are going to find out is that there are only limited improvements to comprehension. What’s more, the issue of reading instruction is becoming politically polarized and incorporated into right-wing movements to reform schools because they see it as a vehicle for removing sociocultural considerations from schools.

All the worst people love the Science of Reading

Normally I don’t go for guilt by association arguments but one of the points I’ve made in the past is that education reforms that appear grassroots or parent-driven are, in fact, long-term conservative advocacy projects. The Science of Reading may be just that. It doesn’t make the science of reading wrong, but it does mean we should embrace a questioning attitude. I’m going to quote University of Wisconsin assistant professor Elena Aydarova at length here:

I think that's the part where remembering who the key players are is really helpful because ALEC as an organization has, as its members, some of the most powerful conservative think tanks in the nation. So Manhattan Institute, American Enterprise Institute, Fordham Institute, they're all involved in their activities and these are the organizations that are actively engaged in promoting SOR and specifically emphasizing that there has to be standard curriculum and evaluation has to be tied around that standard curriculum.

Professional development has to be tied around to that curriculum. These are the same organizations that are saying that any controversial, and again, air quote, air quotes materials have to be removed from school libraries, and children should not be exposed to any diverse literature or books.

Similarly in terms of the parental organizations involved in the movement, Moms for Liberty have been very active in the book banning movement, but they have also been active supporters of SOR. They are not universally right, because they do have some chapters that have raised questions even about the super conservative curriculum that is being implemented.

But nevertheless, they do support this movement. And I think what this helps us see is that this SOR with the capital letters is entangled with the conservative education reform movement that is not just about profits for the private sector, which we see happening, but is also about an ideological transformation of what happens in school.

So the organizations that support SOR also are fighting, for example action civics. They don't want activists raised in our social studies classrooms. They want very conservative birthrights curriculum that was developed with the funding from Koch Foundation. So you can see how SOR fits into this bigger, broader agenda because through the curricula, through the testing, through the transformations and how teaching and learning will now be happening, it is a move to much more traditional values. Right? Why are Moms for Liberty supporting this in their social media? They talk about how the classroom should be, where the teacher stands in the front, and students are sitting in rows and repeating what the teacher says.

So it is actually an onslaught on progressive pedagogy. It is actually an attack on civil rights and social justice 'cause the people who support this movement, or who are writing materials for this movement question the agenda of justice, equity, and diversity. Hirsch, Ed Hirsch, who developed core knowledge language arts, blames multicultural education for the achievement gaps.

Because he says it's this multicultural education that teaches kids that they're victims of the system. What we need to give them is core knowledge that will teach them to be patriots who will pledge allegiance to the state.

I think you see where this is going. Thanks for reading.