- Scholastic Alchemy

- Posts

- Is Education Just Vibes Now?

Is Education Just Vibes Now?

What happens when we care more about what education feels like than if kids are learning anything?

Welcome to Scholastic Alchemy! I’m James and I write mostly about education. I find it fascinating and at the same time maddening. Scholastic Alchemy is my attempt to make sense of and explain the perpetual oddities around education, as well as to share my thoughts on related topics. On Wednesdays I post a long-ish dive into a topic of my choosing. On Fridays I post some links I’ve encountered that week and some commentary about what I’m sharing. Scholastic Alchemy will remain free for the foreseeable future but if you like my work and want to support me, please consider a paid subscription. If you have objections to Substack as a platform, I maintain a parallel version using BeeHiiv and you can subscribe there.

The Vibes They Are A Changing

There’s been something of a trope in recent years to attribute everything to vibes. Kayla Scanlon, for example, coined the term “vibecession” back in 2022 to describe the disconnect between the generally positive economic situation under Biden and the generally negative views of the population. Inflation was trending down but people said it was going up. Unemployment was at record lows but people felt like it was much higher. People weren’t just expecting a recession, they felt like we were already in one. Note: we maybe still aren’t, even with all the economic uncertainty right now. Her use of gen-z parlance for the crystallization of a variety of social, psychological, financial, and economic disconnects into a single phrase really took hold and gained a lot of traction in the media.

Fast forward to this winter and much of the climate around Trump’s victory was attributable to vibes. Ezra Klein made the point that Trump’s victory was narrow, arguably worse than if a normie republican had been running. Yet, everyone was acting like Trump won an insurmountable majority and had a broad mandate to rule like a king. He noted in that piece that people paying attention to vibes may have seen this coming.

In July of 2024, Tyler Cowen, the economist and cultural commentator, wrote a blog post that proved to be among the election’s most prescient. It was titled “The change in vibes — why did they happen?” Cowen’s argument was that mass culture was moving in a Trumpian direction. Among the tributaries flowing into the general shift: the Trumpist right’s deeper embrace of social media, the backlash to the “feminization” of society, exhaustion with the politics of wokeness, an era of negativity that Trump captured but Democrats resisted, a pervasive sense of disorder at the border and abroad and the breakup between Democrats and “Big Tech.”

I was skeptical of Cowen’s post when I first read it, as it described a shift much larger than anything I saw reflected in the polls. I may have been right about the polls. But Cowen was right about the culture.

The reality of Trump’s narrow victory is less important than the shift in the culture that has accompanied it. That shift, Cowen and Klein say, is creating a meaningful real impact in how our governing institutions, media, and the populace respond to Trump. Some have even gone so far as to compare it to Mao’s Cultural Revolution in mid-century China. Are the vibe-ists overstating their case? Yeah, probably. Since those articles, a lot of the sheen has come off Trump’s “dear leader” persona. But, vibes are still a useful analytic tool so let’s use them.

Edu-vibes: affect is more important than effect now

I’ve posted twice recently about my sense that policy makers, political leaders, and other educational stakeholders have stopped caring much about whether every kid receives a good education or that every kid succeeds. It turns out I am not the only one who has noticed. Writing in the New York Times, Dana Goldstein makes the same point I am making.

What happened to learning as a national priority?

For decades, both Republicans and Democrats strove to be seen as champions of student achievement. Politicians believed pushing for stronger reading and math skills wasn’t just a responsibility, it was potentially a winning electoral strategy.

At the moment, though, it seems as though neither party, nor even a single major political figure, is vying to claim that mantle.

Goldstein makes the excellent point that both parties are actually talking about schools quite a bit. What they’re not talking about is learning.

President Trump has been fixated in his second term on imposing ideological obedience on schools.

On the campaign trail, he vowed to “liberate our children from the Marxist lunatics and perverts who have infested our educational system.” Since taking office, he has pursued this goal with startling energy — assaulting higher education while adopting a strategy of neglect toward the federal government’s traditional role in primary and secondary schools. He has canceled federal exams that measure student progress, and ended efforts to share knowledge with schools about which teaching strategies lead to the best results. A spokeswoman for the administration said that low test scores justify cuts in federal spending. “What we are doing right now with education is clearly not working,” she said.

Mr. Trump has begun a bevy of investigations into how schools handle race and transgender issues, and has demanded that the curriculum be “patriotic” — a priority he does not have the power to enact, since curriculum is set by states and school districts.

None of it adds up to an agenda on learning.

Democrats, for their part, often find themselves standing up for a status quo that seems to satisfy no one. Governors and congressional leaders are defending the Department of Education as Mr. Trump has threatened to abolish it. Liberal groups are suing to block funding cuts. When Kamala Harris was running for president last year, she spoke about student loan forgiveness and resisting right-wing book bans. But none of that amounts to an agenda on learning, either.

I think this is a great framing and reminds us that probably the hardest thing about school policy and curriculum and all the other complexities we encounter is the actual learning. What today’s reforms have in common is that they are all about the vibes. Trumpets want school to feel patriotic while the left wants community. Neither one expresses much interest in what the kids learn so much as how it feels to them that kids are in a space that is ideologically pleasing to their side. I would add that learning maybe hasn’t ever been the main purpose of public schooling anyway. So, for the first section of Goldstein’s piece, I’m pretty much on board. That feeling does not continue.

Knowledge does matter

Now, her article goes on to talk about knowledge building curricula as the next big thing and I don’t have a strong opinion there. Background knowledge is great but it’s not enough to say “just build knowledge”. There are battles over what counts as knowledge, who’s history gets included or excluded, and so on. These aren’t theoretical objections either! The example from Goldstein’s article shows that knowledge building curricula are engaging in some, uh, very specific choices to frame history in a certain way.

In one classroom, in northeast Louisiana, you can see several ideas that have emerged far from the spotlight of national politics.

One recent afternoon at Highland Elementary School, where 70 percent of students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, a diverse group of fifth-graders sat, rapt, as their teacher, Lauren Cascio, introduced a key insight: that the Renaissance, the Scientific Revolution and the Reformation all occurred during the same period of human history.

Ms. Cascio reviewed vocabulary words that students would need: heretic, rational, skepticism, heliocentric. Then, over the course of an hour, 10- and 11-year-olds broke into groups to discuss why Leonardo da Vinci was interested in human anatomy. They wrote about how the ideas of Copernicus and Galileo differed from those of the ancient Greeks.

If you’re not a careful student of history, you may miss that there’s an anti-Catholic agenda here. Catholics, after all, are the bad guys who tried to quash science, stifle non-religious art and medicine, and remain steadfastly attached to backwards ancient beliefs. Even the vocabulary words form a nice story where rational skeptics who subscribed to the heliocentric view were branded heretics. To some extent this is true but in a lot of crucial ways it’s also incomplete and stilted and misses that the church did eventually come around and accept science as a meaningful component of revealing god’s creation. I also have a feeling that this curriculum makes no mention of Bartolomé de las Casas and his role in establishing modern conceptions of human rights (not that it did much good for hundreds of years but being the first European to argue indigenous people are fully human and deserve rights is important).

I’m not here to mount a defense of Catholicism but rather to point out that knowledge and how we present it, especially when it comes to history and current events, politics, sociology, and economics, is contestable. Presenting knowledge as settled trades completeness for simplicity because being more complete is hard. You may expect that older kids get more of that completeness and complexity, but I’m not so sure that’s true. They may get more detail, but the story being told often remains the same. “Leonardo wasn’t free to learn human anatomy because the evil Church forbade it” doesn’t suddenly become a historiological study of corpse theft or a theological discussion of the requirements for entering heaven once a student enters 8th grade. And, of course, do we even get to learn that other cultures were working with continuously evolving knowledge of anatomy going back 2200 years? China and India need not apply, it would seem.

Getting it right is actually important

Dana Goldstein’s article includes another important illustration of why knowledge actually matters but telling stories about things gets in the way. In the middle of the piece, she tells a history of why the education reform movement of the 2000s went by the wayside. Goldstein, as a journalist, is compelled to treat both sides of an issue as roughly similar. Part of it with this piece is also that she’s trying to argue there’s a third way out of this polarized culture war trap we’ve gotten ourselves into. In order to make this work, however, she chooses to get history wrong.

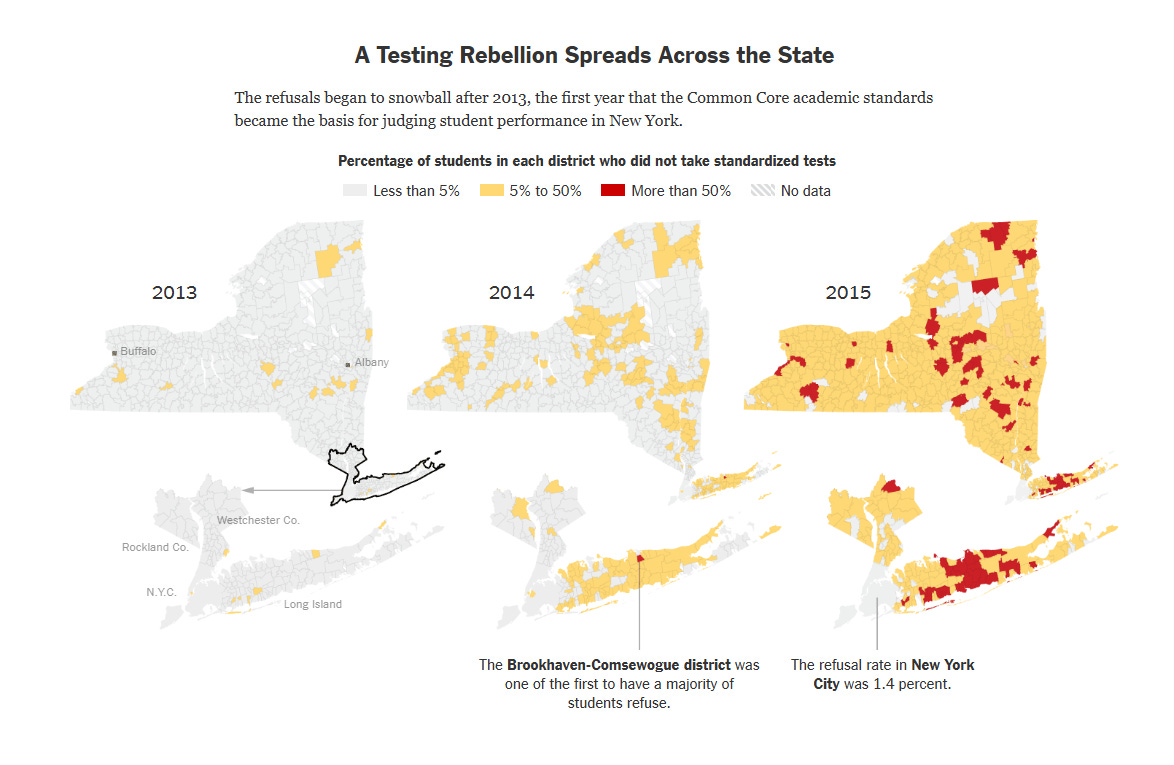

All of this contributed to a potent anti-education-reform movement, led by teachers and parents. On the right, there was angry resistance to any kind of federal mandate over local schools. On the left, a vocal group of parents began to refuse standardized tests; in 2015, 20 percent of students in New York opted out of state exams.

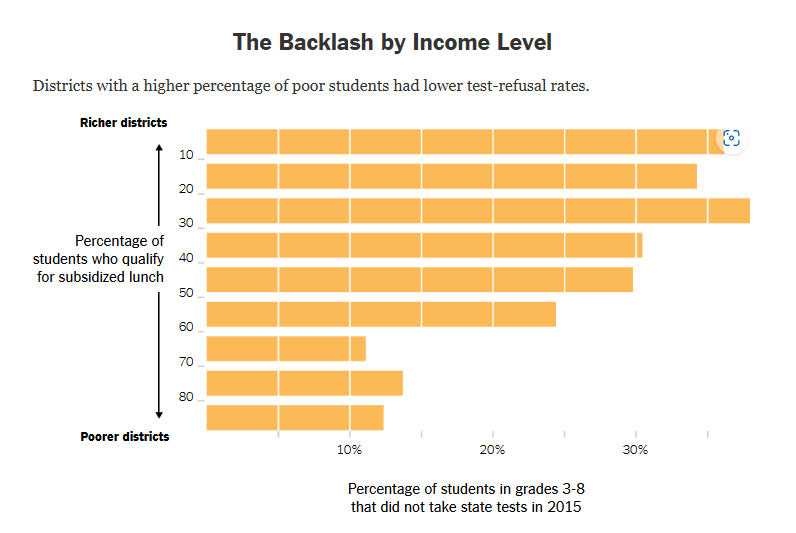

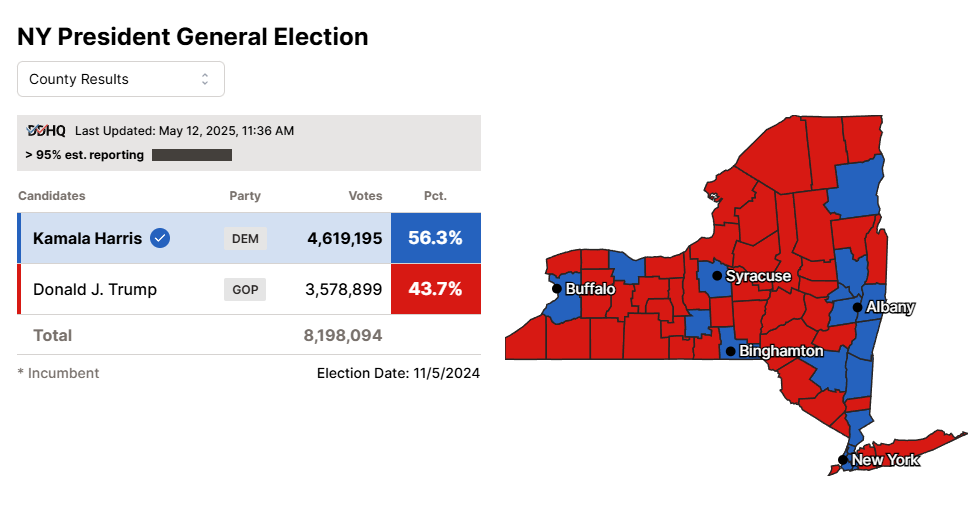

A pox on both your houses, right? Wrong. The opt-out movement was not a product of the left, despite advocacy of teachers unions. If you look at New York, since that’s the exemplar of the left she chooses, you can see that the places with the most opting out were not the most liberal ones. True-blue New York City with its powerful left-aligned teachers union had an opt out rate of 1.4% in 2015, the year Goldstein chooses to cite. Where was the opt-out movement centered? The mostly white, conservative, and wealthy enclaves of Suffolk County, Long Island and some rural upstate districts.

From the same article:

And here’s the presidential election results for New York.

source

Now, the school districts don’t specifically match county boundaries but there is a lot of overlap between red-aligned counties and school districts where opt-out was most prominent. Something similar happened in neighboring New Jersey. Thing is, this opt-out data is from the New York Times. There was a great accompanying the data all about which parents and communities were upset. Dana Goldstein is also writing for the New York Times and her byline says she has been “reporting on education since 2007.” She couldn’t be bothered to check some basic facts about the obviously important opt-out movement? She couldn’t remember a major education story from ten years ago? Her editors didn’t think to look back at their own reporting, reporting I found in five minutes with Google, just to see if it stands up to the most basic level of truthfulness?

No. Because what matters is the vibes. Goldstein and the New York Times need us to feel like both sides are to blame for our current educational malaise. To do this, they need to tell a story where conservatives are not the primary antagonists to public education, even if that departs from the reality a bit. It doesn’t matter if pro-reform conservatives were working on behalf of religious groups. It doesn’t matter that the people opting out of state exams were also Trump voters in wealthy white suburbs. They need us to feel like the way out of our problems is if we would only just care about kids gaining knowledge again even if that means presenting inaccurate knowledge in order to make the point they want to make. As JD Vance famously said, “If I have to create stories so that the American media actually pays attention to the suffering of the American people, then that’s what I’m going to do.” It’s all vibes now. It’s all stories we’re creating to draw attention somewhere we want it to go.

Fighting vibes with vibes may work, I have no idea. My preference, though, is to let true things be true and hard things be hard. It’s okay to make the case that both sides operated in a way that allowed a limited set of reforms to occur. It’s okay to make the point that those reforms were somewhat successful for a bit but were also deeply unpopular. It’s not okay to misrepresent where the reforms were most unpopular or ignore the political implications of rich white people tearing down the last generation’s school reforms and replacing them with today’s vibes-forward preference for vouchers and parent choice and patriotism.

If you’re going to champion knowledge, then you can’t be in the business of obscuring the facts.

Thanks for reading!