- Scholastic Alchemy

- Posts

- Links and Commentary 1/23/26

Links and Commentary 1/23/26

Recent Curricular History, Wag the Curricular Dog, All EdTech is Bad, Mamdani Baby Boom?, If we're going to grade schools...,

Hi! This is Scholastic Alchemy, a twice-weekly blog where I write about education and related topics. Wednesday posts are typically a deep dive into an education topic of my choosing and Fridays usually see me posting a selection of education links and some commentary about each. If Scholastic Alchemy had a thesis, I suppose it would go a little like this: We keep trying to induce educational gold from lead and it keeps not working but we keep on trying. My goal here is to talk about curriculum, instruction, policy, public opinion, and other topics in order to explain why I think we keep failing to produce this magical educational gold. If you find that at all interesting, please consider a paid subscription here, or at the parallel publishing spot on Beehiiv. (Some folks hate the ‘stack, I get it.) That said, all posts are going to remain free for the foreseeable future. Thanks for reading!

Recent Curricular History

This probably could be a post of its own but I’ll drop it here for now and maybe expand on it next Wednesday. Timoth Shanahan is one of the leading reading researchers of the 20th century and his expansive career gave him the opportunity to sit on the hugely important National Reading Panel back in the late 1990s. The Report of the National Reading Panel (NRP) in 2000 was meant to be the final, official word on evidence-based reading instruction. It was meant to end the reading wars of the 1990s which had been waged between phonics and whole-language approaches. He even sat on subsequent panels for the US government, the National Early Literacy Panel and the National Literacy Panel for Language Minority Children and Youth. The guy has had a front row seat and personally created much of the high-level policy and research that continues to shape literacy today. He continues to write both on his own website and on Substack.

He penned a recent post about our problems with designing reading curriculum, in part because educators lack stable agreed upon definitions. In particular, he thinks that the term curriculum is used to broadly.

These days my pet peeve is with the unfortunate explosion of the term “curriculum.” It used to mean only those things we wanted students to learn – that is, the curriculum detailed what we wanted kids to know or be able to do. That was it.

These days curriculum include almost everything. Textbook programs are often referred to as “the curriculum.” So are educational standards. Such colloquial shortcuts may be excusable – though I suspect they are more due to sloppy thinking than verbal short cuts.

Even fine scholars treat curriculum as an almost borderless concept. It has become common to describe curriculum as including content, instruction, assessment, and evaluation (e.g., Prideaux, 2003). In other words, curriculum is pretty much everything that teachers do.

If you’ve been reading Scholastic Alchemy for a while, you may recognized that I disagree with Shanahan on this point. For one, there’s a long history of kids learning things that are not explicitly part of the approved textbook curriculum but are, instead, downstream from how teachers teach. If I followed my explicit structured phonics curriculum perfectly but also punched kids every time they tried to pronounce a diagraph, you’d better believe they learned not to say diagraphs. It might be child abuse but it’s still a pedagogical choice and is therefore curriculum. Beyond that somewhat absurd example, I also disagree with the history we’re getting from Shanahan here. Curriculum has been very broad for a long time. Even if we look at something like Taylorism, in which educators sought to apply principles of scientific management to the classrooms of the 1910s and 20s. These principles required standardization of assessments, content, instruction, and evaluation of both students and teachers. Contra Shanahan, curriculum has been a broad concept for a very long time, probably always. Thing is, someone like Shanahan knows this history. So what’s he really getting at here.

That we want kids to learn to comprehend texts should mean that we spend time guiding them to surmount the challenges that such texts pose. We should be making sure they can read the kinds of words these texts use – breaking the words down and sounding them out (instruction). Kids also should be developing fluency with these kinds of texts, practicing with various texts and receiving feedback and guidance (instruction). Likewise, they should be increasing their vocabularies from these instructional texts and learning how to figure out sentence meanings and how to connect ideas across the texts.

On top of that, we should be making sure kids know a lot about their world, getting them to read worthwhile texts during their instruction and on their own time. We shouldn’t neglect the value of social studies, science, music, art, and gym classes for building knowledge either, and we should ask parents to help too – getting their kids to read at home and involving them in knowledge building activities (yes, television can be a knowledge-building activity).

In other words, we should be teaching kids how to read texts and should be enabling their reading of texts!

Instead, what happens far too often is teachers and principals focus on having kids practice answering the kinds of questions they might see on an assessment – as if it were the questions that mattered, and not the texts. As ACT reported, when students can read texts well, they can answer any kind of questions about them; when they can’t read the texts well, they struggle with any question type (ACT, 2006).

He says this happens because, in part, teachers confuse these prep-style activities for an actual curriculum.

The failure to distinguish curriculum from instruction encourages too many teachers to choose activities they prefer, that they’re confident with, and that they think kids will like. These activities may not be the most powerful avenues to the learning goals, but they aren’t even thinking about that. For them, the activities have become the curriculum.

So, my complaints notwithstanding, I think there’s an interesting critique here. To me it seems like it has a few parts. What do teachers and principals understand good curriculum to be? What do curriculum publishers and designers understand good curriculum to be? How do accountability frameworks, especially standardized testing, incentivize treating the questions as more important than the texts, creating bad curriculum? None of that seems to require narrowing the scope of curriculum to just what’s printed in the classroom materials.

Wag the Curricular Dog

Because of what I wrote above, I thought I’d link a related post Whitney Whealdon wrote last fall that somehow slipped by my noticing. She says that The System is Teaching the Test.

Today, many classrooms don’t just include assessments—they are built around them. In too many cases, the test has become a “shadow curriculum” that is, in some ways, more impactful on student learning than the officially adopted curricula.

Teachers are asked to align instruction to standards and benchmarks not as guides for rich instruction, but as blueprints for the test. Curricula are written to maximize test performance. And schools are judged on the numbers. The result? The assessment tail is wagging the curriculum dog.

She makes a great point about reading comprehension as something better suited for science and social studies than today’s ELA classrooms.

When assessments are built around standards, teachers are led to believe that teaching standards is the same as teaching comprehension. But comprehension is not the ability to answer a multiple-choice question about the main idea. It’s the deeply human act or process of constructing and integrating a mental representation of meaning. The standards that we’ve identified are really only small clues into what is actually happening in our brains to make sense of what we read.

Most standards are only proxies for this process. Yet the push for measurable outcomes has led to comprehension instruction being built around isolated questions that may or may not align with the actual meaning of the text, and they rarely build toward deeper understanding.

Ironically, I believe that comprehension, which most classify as the focus of ELA classrooms, can be assessed more authentically in science and social studies than in ELA. In science and social studies, students must use their comprehension to make connections to build knowledge, explain concepts, or draw conclusions and express evidence-based opinions. They are applying their knowledge and associated thinking skills to generate new knowledge about relevant topics. When students read about ecosystems and explain cause and effect or interpret a historical document to understand motives, they’re demonstrating comprehension.

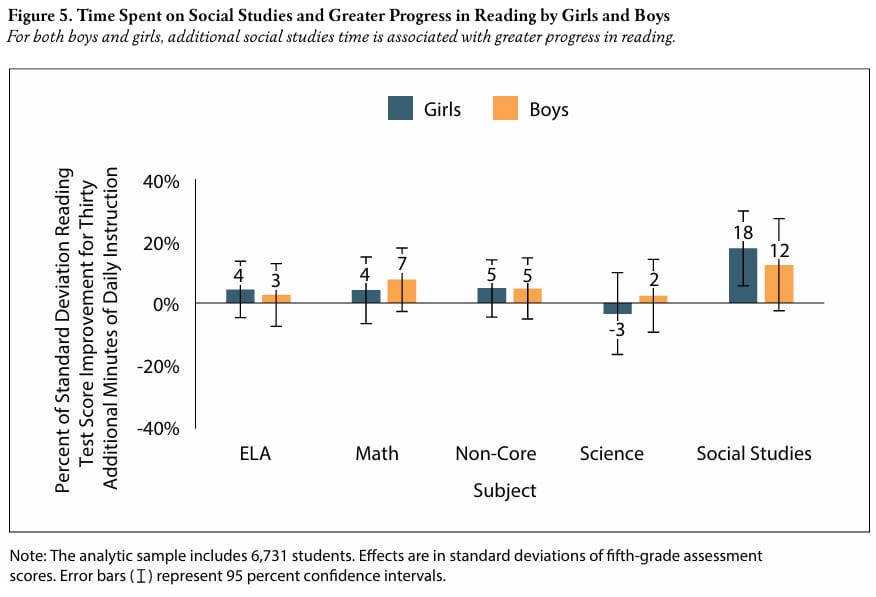

I don’t think this is ironic at all. There’s solid evidence that time devoted to Social Studies leads to greater reading growth (although science is maybe counterproductive? Would like to know more).

source

Back to Whealdon:

Here are three things educators, curriculum designers, and education leaders can do now to support learning through assessments:

Use assessment data diagnostically, not for evaluation. Focus less on numbers and more on what students actually did and said. If possible, provide teachers access to the items themselves, not just reports.

Build curriculum that prioritizes knowledge-building and meaning-making. Align to learning over standards. Center comprehension instruction around rich, knowledge-building text sets. Provide a robust classroom library so that as kids want to learn more, they have access to more texts.

Advocate for assessments that reflect real learning. While we didn’t set out to build a system that teaches to the test, we’re there now. Let’s figure out how we can measure what really matters. AI tools might be able to help to surface insights that are too complex for traditional systems. If used wisely, AI could help us analyze patterns in student thinking, offer real-time feedback, and even create more individualized assessments that respect context and value knowledge. The challenge is making sure we use AI to deepen learning, not just to make our flawed systems more efficient.

All Ed Tech is Bad

There’s been some recent congressional testimony about the counterproductive role of technology in the classroom. I don’t usually like congressional testimony as a way of getting at a useful understanding of the world because, especially today, congress critters will invite hopelessly biased partisans to come grandstand about their preferred point of view. In this case, though, I think there’s kind of a bipartisan consensus here that schools need help dealing with technology. We’ve finally recognized that the proliferation of cell phones and social media are bad for youth but one of the byproducts of that realization is the call to reevaluate classroom technology overall.

Good. If you take the above critiques about curriculum, instruction, and assessment seriously, then you recognize that instructional technology is now the primary vehicle for delivering those things. Obviously, all of the above complaints can happen without vertically integrated classroom tech, learning management systems, fully digital curriculum, and electronic assessments but there seems to be something especially awful about learning from screens. Beyond all that, there are also lots of negative aspects to the tech unrelated to instruction, such as distraction, access to sexual imagery, mental health, and the inability of school systems to ensure the safety of children online. Standardizers are our children’s greatest enemies in this regard because ed tech allows them the level of scale and control they seek to ensure proper standardization. How about teaching kids cursive, instead?

Mamdani Baby Boom?

Sometimes the pro-Mamdani glazing is a bit much, but I do want to highlight an interesting piece about whether his push for more public comprehensive childcare would lead to a baby boom in New York City.

The birthrate in New York City has been dropping for decades. The number of babies born in the city fell 21 percent, to 99,000 in 2022, from 126,000 in 2000, even as the population grew.

The costs of groceries, clothing, health care, after-school programs and summer camps add up. The children’s menu at some restaurants starts at $12 for chicken fingers. Private swim lessons can cost $200 per month.

Free child care is part of a broader push to support families in New York. State and city officials are scrambling to build more affordable housing. The state has one of the nation’s most generous paid leave laws, allowing parents to take up to 12 weeks at two-thirds of their pay. Former Mayor Bill de Blasio started free preschool for 3- and 4-year-olds.

Now, one thing to note is that countries with lots of family support systems, such as free/subsidized childcare or guaranteed paid maternity/paternity leave, continue to have lower fertility than the US. It’s not super clear that these policies induce people to have more children. That said, Americans regularly report they want more kids than they end up having and a big part of the challenge here comes from expense and tradeoffs with careers. So, perhaps we should listen to parents when they say that 2-care will encourage them to think more about having children or about having more children.

When Mayor Zohran Mamdani announced that New York City would expand free child care, Mallorie Ekström immediately messaged her husband about having a second baby.

The prospect had seemed too daunting as long as they were spending $2,000 each month on day care for their 2-year-old daughter. Now there was hope that their daughter could get a free preschool seat at 3 and a sibling could get free care at 2.

“I was super excited,” said Ms. Ekström, 39, who lives in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, and works in real estate. “There is just no possible way that we can afford two children in day care.”

New York City is not going to suddenly become an easy place to raise children. But it might become a little less difficult.

Ejiro Ajueyitsi grew up in the Flatbush neighborhood in Brooklyn and said it was hard to afford raising his two young daughters there, spending more than $30,000 each year on child care.

“Now I can try for a boy,” he said with a laugh.

Mr. Ajueyitsi, 41, said he relished sharing the news in a phone call with a friend who grew up with him and moved to Texas because it was more affordable.

“I was like, ‘Did you hear — day care is free,’” he said. “‘Are you coming back?’”

“This genuinely makes me feel like having a child is actually possible,” said Ms. Jameson, 31, who lives in Washington Heights in Manhattan and works as an intimacy coordinator in the entertainment industry.

The comments section in that article is also interesting. I think one underappreciated facet of childcare is the range of opinions around who should be contributing, whether anyone outside of the family should have a role in early childhood, and what role the state should even play. That said, New York seems to be coming down clearly on one side of that argument.

If we’re going to grade schools…

If we are going to give schools A-F letter grades as a way to communicate to parents some information about school quality, how should policymakers and state leaders act toward schools that routinely fail? What if there was a predictable clear factor that you could look at that would tell you if a school was more or less likely to receive a failing grade? Would you, perhaps, use that to target some kind of interventions? Or maybe shut the schools down, as we do in some accountability systems.

Even though Public School Districts have received about 70,000 total grades since 2005 and Charter Schools have received about 21,000, Charter Schools have received nearly 1/2 of all F grades and Ohio’s Public School Districts have received 90% of all As and Bs (and all but 10 A+s!!)

And here’s how the public schools look.

One thing to note is that Ohio introduced a new, more rigorous school rating system in the 2012-2013 school year. After an initial downward trend, Ohio’s public schools reduced their D&F ratings while increasing their A&B ratings while Ohio’s charters have never had higher numbers of A&B ratings than D&F ratings.

If I were looking for a predictor of a school receiving a failing grade, indicating poor quality and bad outcomes for students, then one of the first things I’d do is ask whether or not it’s a charter school. If I were making state school policy in Ohio, then I would be looking at how to reduce the number of seats in the charter sector as a whole because it seems far more likely that the children of Ohio and the taxpayers of Ohio are being poorly served by charter schools.