- Scholastic Alchemy

- Posts

- Links and Commentary 11/15/25

Links and Commentary 11/15/25

Election and Education Tea Leaves, Reducing Chronic Absenteeism, California College Preparedness, Parent Demand Signals, Gifted Education “Straight Talk”

Welcome to Scholastic Alchemy! I’m James and I write mostly about education. I find it fascinating and at the same time maddening. Scholastic Alchemy is my attempt to make sense of and explain the perpetual oddities around education, as well as to share my thoughts on related topics. On Wednesdays I post a long-ish dive into a topic of my choosing. On Fridays I post some links I’ve encountered that week and some commentary about what I’m sharing. Scholastic Alchemy will remain free for the foreseeable future but if you like my work and want to support me, please consider a paid subscription. If you have objections to Substack as a platform, I maintain a parallel version using BeeHiiv and you can subscribe there.

Sorry to be a day late! I spent the day out and about with the Mrs. and our baby so I never sat down to pen the post.

Election and Education Tea Leaves

Jennifer Berkshire offers us an overview of the educational implications of Nov 4th’s elections. I don’t know how much to read into the overall blue wave stuff and you can certainly find coverage arguing all kinds of things but her focus on what this means for education is important and under-covered by others. For example, there was a huge blow-up over Zohan Mamdani’s plans to end NYC’s gifted testing of 4 year-olds but now that he’s won the election, there’s little mention of his plans for education at all. This is made doubly interesting because the mayor of New York City has direct control over public schools. It’s one of the few campaign promises he made that he actually has the authority to enact, but most coverage of of things like rent control and taxes that the mayor doesn’t directly control. Even his promise of universal childcare has taken a back seat to coverage of other issues. (That said, Karen Vitiates penned an essay about Mamdani that I link below. Still, it lives on Substack, not, I dunno, the front page of the Times.)

Anyway, I am linking Berkshire for one other reason. Her coverage is a good reminder that parents and the general public hold some idiosyncratic views about education that don’t fall neatly into party affiliation or polling buckets. For example, Republicans in Mississippi were seeking to squander their “miracle” status by cutting school funding and enacting vouchers leading to democrats flipping three seats in the legislature. This, of course, runs contrary to national level commentary:

We’ve now had 12 years of terrible education statistics. You would have thought this would spark a flurry of reform activity. And it has, but in only one type of people: Republicans. When it comes to education policy, Republicans are now kicking Democrats in the butt.

As much as we’re also told that voters dislike Democrats’ education policies, it really only looks like detracking (and, again, a very particular version of detracking that eliminates advanced classes, the polling did not ask about detracking plans that increase access to advanced courses) is a negative for Democrats. For example, Democrats receive decent levels of support for free school lunch and head start funding. I will say, though, the polling from Deciding to Win covers education very sparsely and leaves out some of the biggest issues that have generated recent controversy. Yes, the odd detracking question was there but what about, say, testing and accountability? What about retention? What about vouchers? What about curriculum reforms or phonics or career and technical education or phones in schools or any number of other things? Well, the methodology of Deciding to Win only worked with issues that had a clear partisan valence. That is, they only looked at issues when their sample regarded a policy as “belonging” to either Republicans or to Democrats and then evaluated how important the policy was and how trusting of the associated party the respondents were. Those gaps in coverage, then, make sense because for many people education does not have a strong partisan valence. People aren’t looking at curriculum reform as a political issue (though perhaps they should) so Deciding to Win isn’t going to be polling about it.

I wonder, too, if one of the biggest problems we’re seeing with education is that everyone is sort of waiting for state-level policy to fix things but states are slow to change and the ones that are moving quickly are enacting unpopular voucher programs or very top-down culture war stuff that parents don’t really love. The deal that moderates made when they elected conservative culture warriors like Glenn Youngkin in 2021 was that they’d tolerate the right-wing culture war stuff so long as it came with some sense that schools were more responsive to parents and local control. Instead, these figures consolidated power at the state level, did the culture war stuff anyway, and mostly did not improve schools. If anything, the efficacy of public schools detracts from the overall conservative goal of funding Christian schools. Seems like voters are seeing through this to some extent, but I expect we’ll have to wait for midterm elections to get a clearer picture. This means changes are slow, are always political first, and then flow downstream from whatever political considerations are in the driver’s seat each election cycle.

Reducing Chronic Absenteeism

Perhaps the most intractable challenge right now is the large number of chronically absent students. My guess is that if we looked at students who were chronically absent from school, missing 10% or more of the school year, we’d see that a lot of schools’ poor performance on accountability tests is because of these kids. You have to be in school to, you know, learn what the schools are teaching. Anyway, EdReports takes a look at one district in California and the role their counselors played in reducing chronic absenteeism.

Alma Lopez, lead school counselor at Livingston Union, said that school counselors run regular “student information reports” and meet with students who are earning multiple Fs in certain subjects, struggling to make it to school, or have received multiple office referrals for detention or suspensions.

“We’re looking at the data to identify the students initially, and then digging a little deeper to try and find what’s the root cause of the challenge they’re having,” Lopez said. “And then looking at what could be an intervention for that student in a particular situation.”

A student struggling to complete assignments, for example, could be encouraged to join a six- to eight-week group intervention on motivation and growth, while another might join a tutoring group focused on study skills. A student struggling with chronic absences could receive help with transportation, while another could sign up for sessions with a medical or mental health provider to address health issues.

One lesson of scholastic alchemy is that solutions that work well in one context may not generalize to others. Indeed, they usually don’t and education history is littered with interventions that failed to scale. So, we shouldn’t necessarily be looking at the specific solutions they implemented but at their process for arriving at solutions that worked in their school. These counselors meet with every student and family in 4th and 7th grades, they review student attendance and grades regularly, they teach classes on career guidance, long term academic planning, SEL, and other topics in addition to the typical school counselor stuff and, as the quote above notes, they then use all of that time and energy getting to know students and their families to better tailor interventions to students’ needs.

California College Preparedness

Sticking with California, a recent report by the Senate-Administration Workgroup on Admissions is getting a lot of attention. The report notes that some University of California system universities are having to increase the number of students taking remedial mathematics courses. The commentary around this points to UCSD where more than 12% of the incoming class is going to be enrolled in one of two levels of math remediation. In some cases the missing math skills are things we’d expect students to learn in middle school. While a lot of the commentary here is around the admissions practices (remember, it’s an admissions report), I’d like to make two points. First, we should consider learning that happened during the pandemic to be interrupted or nonexistent. 5 years ago, these kids would have been in middle school. It makes sense to me that their weakest math skills would kick in around those years because that’s when they would have moved to remote learning. We are probably going to see effects like these for years to come as the kids who experienced pandemic schooling move through the K-12 pipeline and into college or the workforce. I’m skeptical that there’s much we can do the erase the effects of the pandemic but that also means we shouldn’t feel like these are structural defects in education.

That said, my second point is that there is a problem progressives and pro-public education liberals should take more seriously. Our education system is not legible. Colleges and universities are having difficulty understanding what students are and are not learning, whether grades and reports contain any meaningful information, and how to make decisions about student admissions and placement. Many, like the UC system, are building their own assessments to do this work (that’s how they knew incoming students needed remediation and how much) but some of that could be shouldered by the SAT and the ACT if only those could be used for admissions. While they were removed from consideration during the pandemic and remain off limits for reasons of equity, I think it is just as inequitable to enroll students in college and then suck up their time with remedial courses because they are not prepared for collegiate level work. In fact, we have decent evidence that more remediation does not increase graduation rates and students requiring remediation are more likely to drop out. Far from increasing equity, we’ve developed a system that brings in unprepared students, separates them out for costly remediation, and leads to more of those same students dropping out. Are the underrepresented poor and minoritized students who were supposed to benefit from this policy better off now? Is it better that the fewer students who successfully pass through remediation go on to graduate normally? Are the ones who drop out “worth it” so that a few others succeed? What good, exactly, have we done here? Once again, a well intentioned policy leads to results that has everyone scratching their head and wondering how anyone thought this was a good idea. It’s scholastic alchemy, folks.

Parent Demand Signals

Chad Aldeman writes that parents oversubscribing to a magnet school, such as TJ in Fairfax County, VA, are sending a signal that more schools like this should be opened. This is, he says, preferable to opening a “normal comprehensive high school”. Since I tend to believe in the opposite approach — indeed, I wrote recently that we need more truly comprehensive high schools, not fewer — I think it’s also important to highlight voices saying something different from my own.

what an opportunity! Fairfax County happens to be home to one of the best public high schools in the country, the Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology (known locally as TJ). Created in 1985, TJ is a magnet school serving Fairfax and other northern Virginia counties. As you might expect given its strong academic outcomes, TJ is extremely popular. Every year it rejects about 80% of the students who apply, and its screening process is so hotly contested that families asked the Supreme Court to weigh in (they declined). Last year, TJ rejected about 2,055 kids1, and the average GPA of all applicants was 3.91.

In other words, Fairfax is home to a super popular school that can’t serve all of the students who want (and deserve) to get in. It should build another one!

Now, he doesn’t really have a huge argument beyond the popularity of TJ in this post. What I’d like to know is, how do the kids who don’t get into TJ do in life? Presumably, denied a chance to attend TJ, they end up indigent living in a van down by the river? While not every Fairfax school is as good as TJ, aren’t they also all quite good? Certainly better than schools in many surrounding DC suburbs and nationwide. Is it better or worse for them to excel in a comprehensive high school where they likely still come out with excellent GPAs, high marks on AP tests, and so on?

By opening another selective entrance magnet school, yes, you are serving lots of kids who could have been successful at TJ but for the limited seats, but you’re also devoting another entire facility and staff just to kids who are pursuing advanced academics under the science and tech umbrella. You’re hoarding the limited pool of teachers who can teach advanced subjects in a school that’s not accessible. Indeed, that’s the word we all need to remember: access. You’re sending the signal to all the parents that the “smart” kids matter more and are more deserving of the districts time and effort than the kids who aren’t headed to advanced STEM academics. I think that gets to the core of my love for comprehensive schooling and my dislike of more and more specialized high schools. Public schools are for everyone and we need to act like kids following a less prestigious, high status path are somehow less important or less deserving of a good education. All kids should have access to the kind of teaching and coursework that happens at TJ. It’s weird to me that people want to limit access to advanced courses until I remember that some people thrive on a sense of exclusion. That is, after all, why Harvard & Co. are “the best.” They are the best because they exclude the most. Low acceptance rates are evidence of how good they are and people like Aledman want public education to replicate that kind of exclusion. Relatedly, see the next link about exclusivity and gifted education.

Gifted Education “Straight Talk”

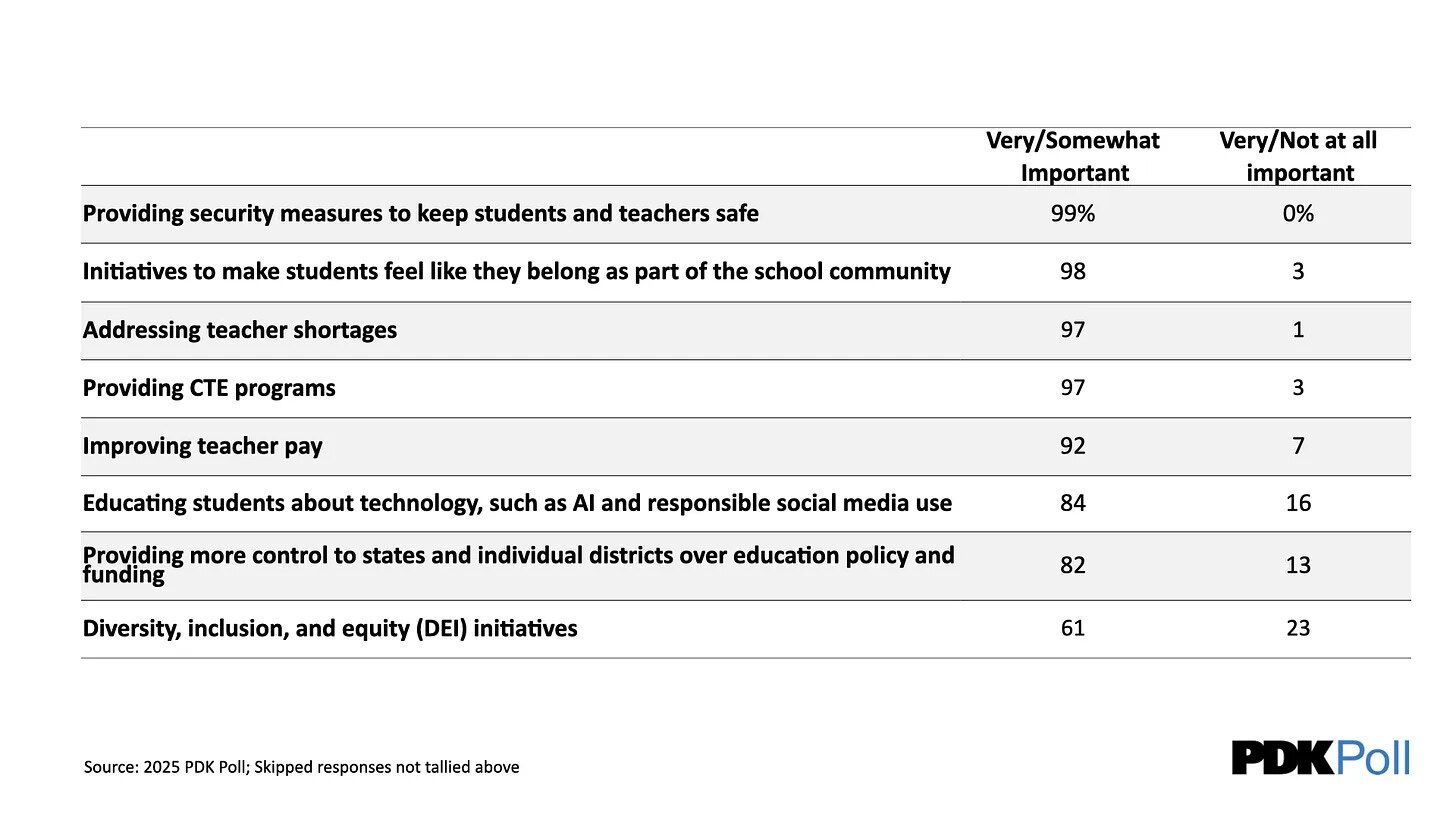

Karen Vaites, who I’ve linked in the past, makes an argument directly opposite what I’ve been saying about Gifted and Talented programs. As I said above, I think it’s important to share perspectives from writers who are writing in the education space but with whom I disagree on certain topics. Vaites is right to lament that education is not higher on voters’ lists of priorities. I too would like education to feature more prominently in elections and for the public to think more deeply about education topics. What I also like is that Vaites pulls on some data that makes me think again, or at the very least, qualify some of what I’ve been saying about parents’ expectations of schools. I have, several times this summer and fall, argued that parents are not primarily concerned about advanced academics and are instead focused on whether their kids’ feel like they belong in school, are safe, and other non-academic concerns. And that probably is still accurate for the nationwide representative polling that I cited, like the PDK poll.

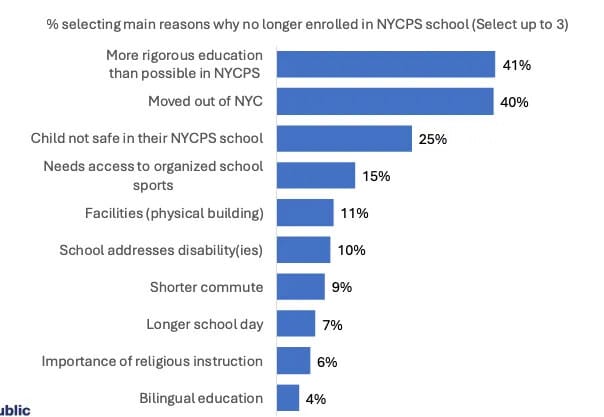

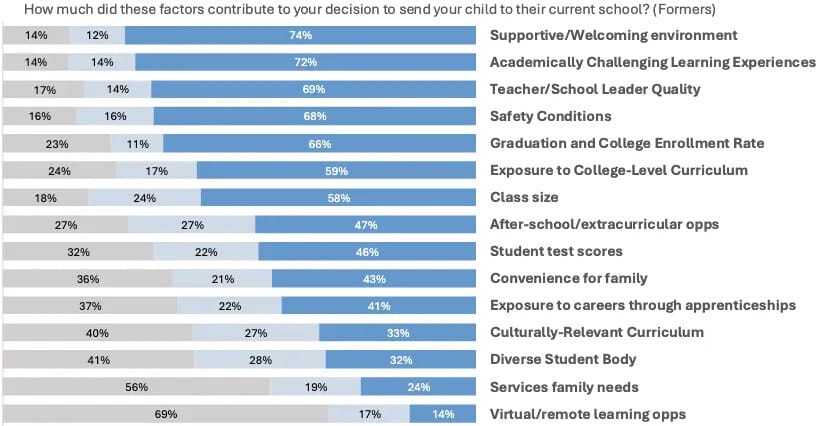

Vaites, though, looks at exist survey data that NYC collects from parents who are pulling their children out of New York City schools entirely. This data shows that these parents did say they cared about having advanced academic options and challenging learning experiences.

via Karen Vaites post

via Karen Vaites post

I have no reason to doubt parents’ responses here but I do have a few issues with Vaites’ interpretation of the data. First off, I’ve mentioned before that in New York state and in New York City, enrollment in gifted and talented programs is very small: roughly 2% of students statewide and 5% of students in New York City are enrolled in gifted programs. There is simply no world where 41% of these kids leaving the city’s public school system were going to be enrolled in gifted classes but for Mamdani’s changing of a test for 4-year-olds. While parents may collectively harbor the delusion that all of their children are going to qualify for gifted programs, they won’t. It’s not a program that most kids could or should be enrolled in. And that brings me to my second point: gifted and talented programs are not supposed to be highly selective pathways to advanced coursework. Yes, yes, I get that in many places, including NYC, that’s how they function, but the purpose of these programs is to help otherwise intelligent kids who struggle to succeed in school. They’re not classes for kids who are successful in school that’s why gifted programs typically do not teach advanced academics and typically do not make kids into academic high achievers. If you want advanced academics to be available for lots of kids, then you should just make a program to do that. Don’t lock them behind exam schools and gifted programming that you’ve contorted into some kind of advanced tracking scheme. Which all brings me to my third point of criticism for Vaites: access. If parents are leaving because their kids are not among the 5% who get into gifted and talented via a test they take when they are 4 years old, why are we advocating against reforms to this system of selective testing? Isn’t the better argument to make an argument for access? Shouldn’t Karen be encouraging NYC or wherever else to do a better job of offering advanced classes and identifying kids who could succeed there? If she does, it’s not super clear that that is her point. Instead we get this kind of muddled call for… doing everything?

It feels reasonable to demand protections for Gifted & Talented programs in New York City because the city is investing in foundations — and it’s working. The two year old NYC Reads initiative is showing promise:

“Reading test scores climbed seven points for New York City public school students who took state exams in the spring, a substantial increase over previous years that comes after efforts to change the way students learn to read… The improvement was especially large for third-grade students, a crucial benchmark because children who cannot read well by then are more likely to drop out of high school and live in poverty as adults. About 58 percent of third-graders showed proficiency in reading, a nearly 13-point rise from the year before.“

I’d like to see as many voices calling on Mandani to maintain — and invest further in — NYC Reads as those seeking to defend G&T.

Let’s pair calls for Algebra in 8th grade and gifted programs in elementary schools with demands for math foundations and knowledge-rich curriculum starting in kindergarten, for the good of American schools.

Okay, so, at least in terms of how he campaigned, Mamdani is not removing gifted programs from elementary schools, just moving them back to 3rd grade. This is in part because of the need to focus on foundational skills in the lower grades and splitting students out into gifted classes this young is both developmentally inappropriate and organizationally complex. She also further muddies the water by bringing in Boston’s schools and writers discussing more nationwide trends.

Karen, focus. You, I think accurately, argue that parents who leave NYC public schools care about advanced courses. You should therefore advocate for increasing access to advanced courses! Arguing that NYC’s gifted program needs “protections” means you’re arguing for a program designed to limit access to advanced courses. You even cite Kelsey Piper’s mentioning of the North Carolina study about how many more kids could succeed in advanced courses if given the chance. If you care about public schools, then the way forward is increasing access so more kids take advanced classes should they (their families) choose.

For all her straight talk, Karen Vaites seems to have ignored the straightest talk of all.

Thanks for reading!