- Scholastic Alchemy

- Posts

- Links and Commentary 6/13/25

Links and Commentary 6/13/25

ICE Raids and School Trauma, Things Fall Apart, People Think They Hated School, Words As Units of Utility, Your Kids Need More Sleep

Welcome to Scholastic Alchemy! I’m James and I write mostly about education. I find it fascinating and at the same time maddening. Scholastic Alchemy is my attempt to make sense of and explain the perpetual oddities around education, as well as to share my thoughts on related topics. On Wednesdays I post a long-ish dive into a topic of my choosing. On Fridays I post some links I’ve encountered that week and some commentary about what I’m sharing. Scholastic Alchemy will remain free for the foreseeable future but if you like my work and want to support me, please consider a paid subscription. If you have objections to Substack as a platform, I maintain a parallel version using BeeHiiv and you can subscribe there.

ICE Raids and School Trauma

There’s a lot of coverage of the growing anti-ICE protests and I don’t have much to say there that hasn’t been said elsewhere. One facet of the reporting that I do want to highlight is the intersection of schools and escalating immigration enforcement actions by the Trump admin. When ICE operates in and around schools, it creates a climate of fear. Maybe they took a star student and athlete, brought to the country as a child, while he was driving teammates home from volleyball practice. Maybe it’s panic among parents and students that ICE is coming to a high school graduation to arrest everyone. Regardless of the actual scale, or whether the enforcement actions even take place at that day and time, people are upset at the thought of losing friends, family, or suffering deportation themselves. This undermines the normal functioning of schools and makes it hard for kids to learn.

CDC

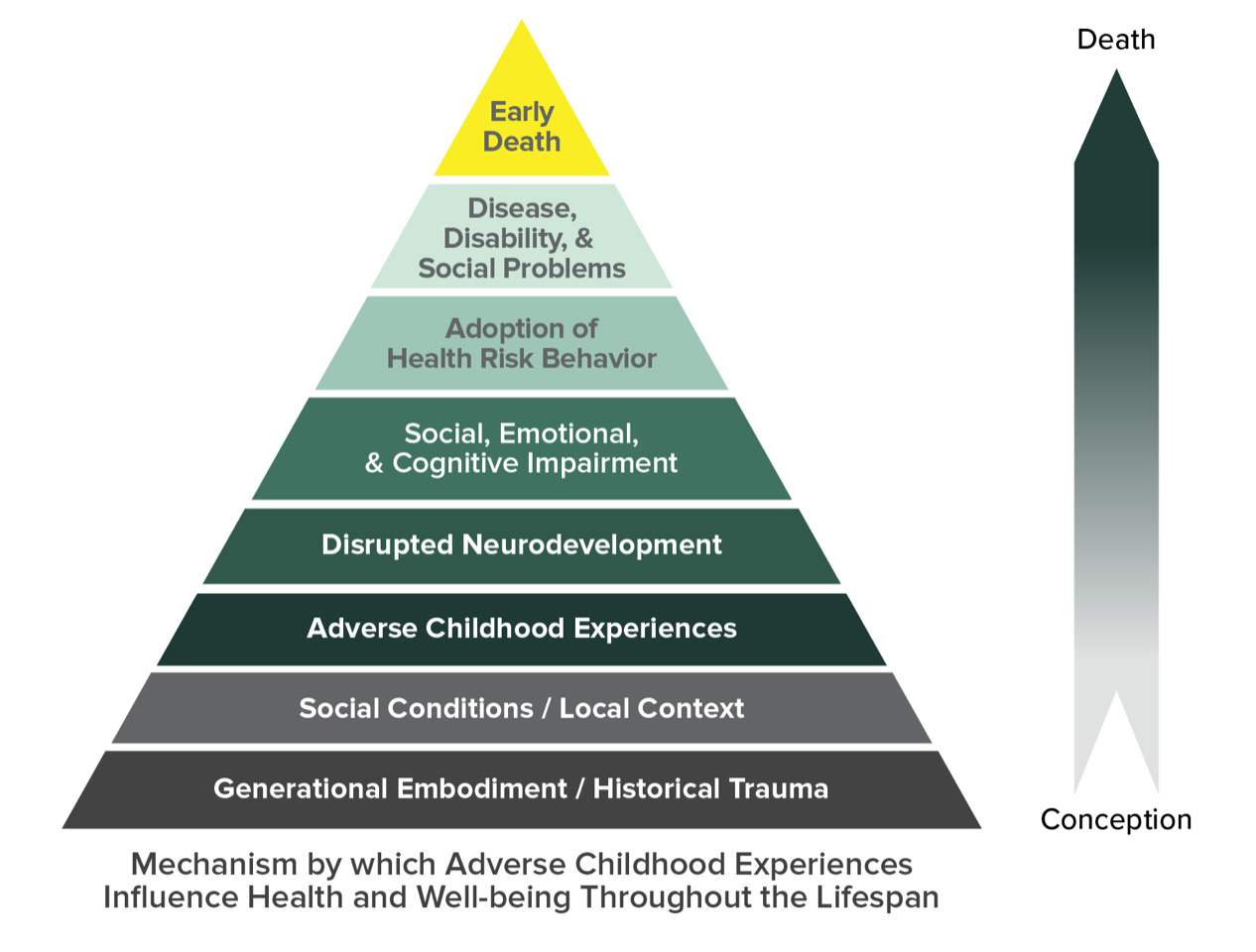

Like I said in my post about school disruptions and again in the post about being skeptical of learning loss, kids are more than academic machines. They exist in the community, they have a social and familial life, and they are aware of the events of the world around them. When school is disrupted, whether by a natural disaster or the fear of an ICE raid, it takes a toll on the school and its students. We have evidence that childhood traumas have long-term impacts on students’ wellbeing, academic performance, attendance, and education outcomes (see here, here, here, here, and here), as well as strong evidence that childhood trauma leads to degraded neurological development, emotional and cognitive impairments, and even early death. There is also a growing body of evidence that immigration enforcement actions in the community cause drops in attendance, lower test scores and pass rates among Hispanic students, and reduced health outcomes for children.

Kids don’t have to be the subject of immigration enforcement actions to be negatively impacted by them. The fear and disruption are real, are happening, and are going to create negative impacts for our schools and students for years to come.

Things Fall Apart

I know I’ve recommended Kayla Scanlon’s newsletter before but if you haven’t subscribed, do it. Her letter this week meditates on the increasing multifurcation of our world. On one hand various era defining shifts in technology portend a time of incredible abundance while on the other hand our economic and social structures are breaking down while on the third hand there’s a government in power that care little for anything beyond its own enrichment and the on the fourth hand there are people caught in the middle trying to make sense of a changing world.

We are increasingly caught between a future promised and the present we're living through. We have apps that can summon autonomous vehicles in minutes while we have ICE raids escalating across the country3 . AI evangelists talk about dancing in fields of daisies now that robots will do all the work while National Guard troops sleep on concrete floors without water (and their service members boo state governors).

If you wanted a perfect image of this contradictions (we are a visual first society after all), I think the burning Waymos in LA4 are pretty searing. People used the frictionless Waymo app and the seamless user experience that the company spent billions perfecting to summon an autonomous vehicle to their exact location, and burnt it.

It’s painfully on the nose, and I would hate to veer into detached-from-reality-metaphorical-thinkpiece but there is something relatively poignant about using the infrastructure of the promised future to reject that future and to also the refusal to keep pretending that this future arriving through our screens has anything to do with the reality people are living in.

The image of the Waymo on fire is a miniature of collapse, used to fuel calls for sending in more troops to LA than we have in Syria or Afghanistan. The contradiction becomes content, the content becomes justification for more contradiction. We scroll past the burning car to see arguments about whether the burning was justified, then scroll past those to see memes about the arguments, then scroll past those to see counter-memes. The cycle feeds itself!

This all echoes Yeats, of course, but I think a different take on the line things fall apart is worth quoting today.

He came quietly and peaceably with his religion. We were amused at his foolishness and allowed him to stay. Now he has won our brothers, and our clan can no longer act like one. He has put a knife on the things that held us together and we have fallen apart.

People Think They Hated School

I read pretty widely, though my overflowing feeds suggest that I don’t keep up with it. One of the more entertaining and interesting writers I’ve come across is Cartoons Hate Her, who writes a blog focusing on social, cultural, political, and fashion commentary. In a recent post, she argues that School is Bad, Actually. It may surprise people, given my general positive disposition toward schools, that I am not opposed to this take. Remember, schools exist to promote social order and keep the population in line. Every other mission they have has been bolted onto this primary goal and in times of turmoil among the elites, schools often slide back into this role of reproducing elites’ power. It’s not surprising to me that many people chafe at the more authoritarian and structured aspects of schooling in the modern US. That’s why when I see CHH write things like this, I am unsurprised:

Despite the fact that I grew up with two intellectual, Ivy Leage educated parents who were both straight-A students, I didn’t see the point in school. It went beyond a typical “I don’t like learning about geometry” thing and into a true hatred for the very concept of school

My sister outperformed me in school in a lot of ways. She had better academics than I did and far outperformed me in athletics. She always says she hated school, and I remember a few times she would cut school and go to, of all places, the library. Wouldn’t have been my choice! But I also more or less enjoyed school so I wasn’t interested in skipping out.

Anyway, the reason I share all of this is, basically, I don’t believe Cartoons Hate Her. I don’t believe it! She went to Harvard. She took advanced courses and even attended a specialized summer camp for academically talented kids where she took college courses early (warning, that post is about people’s, um, personal sexual habits and some social commentary therein, just in case you weren’t expecting the shift in tone). The more of her posts I read, though, the more her elite education and wealth of knowledge shows through. This is someone who did about as well in school as imaginable, attained some decent accolades, enrolled in a very picky university (legacy perhaps, but iirc it wasn’t to Harvard) and has made a career of writing at a time when it’s notoriously hard to make a career writing. School, whatever negatives you may be focused on, clearly didn’t hold her back. My sister is in a similar space. She excelled in college and went on to be an occupational therapist who, by all indicators, is exceptionally good at her work and has succeeded in some higher stress settings that most OTs never encounter.

Clearly not everyone loves school, and you can’t chalk everyone’s success purely up to their performance in school, but I don’t think you get to hate school if you’re someone who clearly excelled in school. You know what people who really hate school do? They fail and drop out. You only think you hate school.

Words as Units of Utility

I need to write a post about the Science of Reading (SoR) and as I’ve been prepping that post, I am thinking I will make it part of the I’m Skeptical series that I’ve been writing each week. One of the big problems I have with SoR in practice is that it too often denigrates the purpose of language: to convey meaning. I say “in practice” because I think anyone who does the research and/or creates the curricula drawing on the evidence knows that meaning making is the point of reading. But when you bring SoR into schools, it’s too often about the first half of reading — understanding the way letters should sound, how those letters fit together into the parts of words, and how those words should sound — and a lot less about fluency, comprehension, and writing. There are some amazing evidence-based programs out there to support writing in the upper-elementary years, for example, and districts just aren’t adopting them because they’re laser focused on phonics and early reading.

This is all on my mind because I was directed to Carl Hendricks’ recent post, The Humility of the Page (tip of the hat to Audrey Watters for linking it). He begins by noting that reading was, for a little while in human history, considered a moral act. That is, reading was part of an important moral education that required readers to “submit to another’s voice, another’s mind, another’s world. It was, in its quiet way, a gesture of humility.” This deeply moral view of reading is one that acknowledges reading can help us develop a common sense of humanity with our fellow citizens. It is all going away.

Today, that kind of reading feels vanishingly rare now and not because the books are gone, but because the conditions that once sustained them have eroded. Solitude, slowness, and sustained attention are no longer default states but acts of resistance. And as those conditions erode, so too does the possibility of the moral work that deep reading once quietly performed.

We are being trained, not explicitly, but implicitly, to treat words as units of utility. Optimised, shortened, and surfaced by platforms whose guiding logic is not comprehension, but click-through. In such an environment, the act of reading becomes flattened: stripped of its reciprocity, its effort, its deliberateness. But something essential is lost in that flattening.

Much of the internet wants us to dwell in shallow, curated versions of our own minds. By encouraging us to constantly turn inward through personalised algorithms, we are no longer invited to encounter authentic otherness, but to loop endlessly within the contours of what we already know, believe, and prefer. We become trapped in a hall of increasingly vacuous mirrors, fed content that flatters, not confronts, until thinking itself feels like friction.

I emphasized a sentence there because I really like the formulation of words as units of utility. Utility is. among other things, an instrumental concept that reduces something’s value to its usefulness for some other thing. Reading is only valuable because it gets us to “click-through” or because it lets us interact with an LLM’s inputs and outputs or because it raises test scores.

Science of reading reforms are so focused on segmenting out the sound-based components of speech and written text, phonemes, that they feel like they are treating reading as an exercise in utility. There’s even a worry that simply knowing how to accurately sound out a word is the equivalent of knowing that word; this is something we call “word calling”. It’s a problem because moving from knowing how to say a word to knowing what that word means is a hard lift. It requires not just definitional knowledge of the word but a broader awareness of syntax, comprehending all the sentences in a paragraph, and understanding any metaphors and allusions that may be a part of the mix.

You, dear reader, probably understood the references above to Yeats and Achebe because you’d read the book and the poem. You probably also connected your memory of those texts to the quote from Things Fall Apart that I included. You probably also connected all of that knowledge to the longer quote from Kayla Scanlon just a little earlier. And all of that probably also played around in your brain forming and breaking comparisons and trying to build out my point conceptually. This is because you allowed me, via reading, access to your brain chemistry. None of that is primarily about the utility of the words I wrote, nor is it enough to say you can accurately reproduce the sounds of the words I have written therefore you comprehend it.

Your Kids Need More Sleep

Tim Daily makes a convincing case that a lack of sleep may be an underrated reason for kids’ poor academic performance.

When discussing our failed COVID recovery, we often describe a widespread mental health epidemic driven by the toxicity of social media, too little time socializing in the real world with friends, and residual trauma from family members lost during the pandemic.

All true. But as we get further from 2020 and our problems linger, it seems like there’s more to the story. In addition to these other factors, COVID exacerbated challenges with sleep by increasing screen time particularly in ways that interfere with healthy nighttime and morning routines. It’s not just how much screen time. It’s when.

The whole thing is worth a read.

Thanks for reading!