- Scholastic Alchemy

- Posts

- Matt Yglesias is Right About Students

Matt Yglesias is Right About Students

But seems like he always wants to be dumb about education

Welcome to Scholastic Alchemy! I’m James and I write mostly about education. I find it fascinating and at the same time maddening. Scholastic Alchemy is my attempt to make sense of and explain the perpetual oddities around education, as well as to share my thoughts on related topics. On Wednesdays I post a long-ish dive into a topic of my choosing. On Fridays I post some links I’ve encountered that week and some commentary about what I’m sharing. Scholastic Alchemy will remain free for the foreseeable future but if you like my work and want to support me, please consider a paid subscription. If you have objections to Substack as a platform, I maintain a parallel version using BeeHiiv and you can subscribe there.

Matt Yglesias published a post Monday saying that America’s students are getting dumber. The headline is obviously built to create a ton of engagement but the post itself is some pretty standard information about NAEP scores and school attendance. You know, the usual stuff we see reported on in the media year in and year out. The factual basis of the post is nothing you haven’t read before a dozen times this year unless you basically read nothing about education.

That’s partly why I want to write about Matt’s post. As a Slow Boring subscriber, I expect more from Matt’s writing than bog-standard reporting and, uncharacteristically, his analysis and opinion are a much smaller component of the post. So let’s figure out why and see if I can make an interesting point about Matt’s post and US education more generally.

Dumb Bait

I’m not taking the bait from the headline about students being dumber but many people online do seem to have fallen for that. While I get that some reflective outrage is to be expected, I think dumb can be oddly accurate here when taken at its common modern meaning. Being dumb is, these days, about lacking critical thinking, being unable to articulate complex thoughts orally or in writing, and lacking focus. If Matt never said dumb but did write that students increasingly struggle with critical thinking, couldn’t explain their thoughts, and had difficulty with executive function then nobody would bat an eye. That’s why, I’d argue, he’s actually right. Students are facing some very common child/adolescent learning struggles but in greater numbers or with more severity than in the recent past. He’s really just repeating conventional wisdom.

What I find way more interesting is that Matt has almost nothing substantial to say and that he even kind of admits a few times that he doesn’t really have a good idea of what’s going on. Over and over he is reduced to using language like “I can’t say why” or making a “guess” about causes of various negative data. He says he doesn’t understand why “[t]here was significant bipartisan backlash to this accountability regime, and it was dismantled on a bipartisan basis during Obama’s second term.” He says he “can’t say exactly why” NCLB era reforms improved test outcomes for students “at the bottom” but also didn’t harm “excellence at the top.”

That’s because, when it comes to education, Matt Yglesias is dumb. He struggles to think critically, instead falling back on the same stances he’s been taking for 15 years. He refuses to incorporate any information other than test scores into his worldview and doesn’t update his thinking about education seemingly at all. Matt doesn’t seem able to explain his thinking clearly, falling back on tired cliches like that learning is exercise for the mind.

It is more difficult for him to read more challenging books (obviously), but he can, in fact, do it and he does, at least a little bit, every day.

And pretty much everything in life is like this. I’m not someone who enjoys exercise, but if I skip it for a while, I get horribly out of shape. So I really try to drag my ass to the gym every week.

A fine Harvard graduate, everyone! Matt also seems unfocused in this post. He starts off saying he actually intended to take the post in a completely different direction but became frustrated by the lack of a simple explanation in the data and gave up.

To be totally honest, Plan A for this post was to look at international data and either show that the decline is a broadly global occurrence (and thus likely due to some global phenomenon like smartphones rather than United States-specific policy choices) or that it was concentrated in the U.S. and a few other countries (and thus likely due to narrow policy choices).

But this question is incredibly difficult to answer.

He doesn’t think critically, can’t explain his reasoning, and isn’t able to focus on complex problems. He’s dumb! Okay, that’s enough dragging on Matt. If there’s one essential through-line for my writing here at Scholastic Alchemy, it’s that there are no easy answers in education. You want an easy answer? Establish universal K-12 schooling for all children. That was the low hanging fruit and we picked it more than a century ago.

Scratching the Record Straight

NCLB and Common Core and RTTT were the biggest attempts at overhauling education nationwide since the invention of middle school. Matt, especially with NCLB, wants very much to say that it was a success. Yes, he admits it’s a limited success but a success nonetheless. He also really wants the death of education reform and the push against measurement to be bipartisan political moves that he can blame for students’ present NAEP weakness. Let’s qualify both of these claims.

Was NCLB a success? Matt says “broadly speaking, in the N.C.L.B. era of accountability at the bottom, all students were improving!” Well, kinda. What looks to have improved was Math scores while reading scores remained flat. Math score improvement was almost entirely in the 4th grade with milder gains in 8 grade and almost no gains in 12 grade.

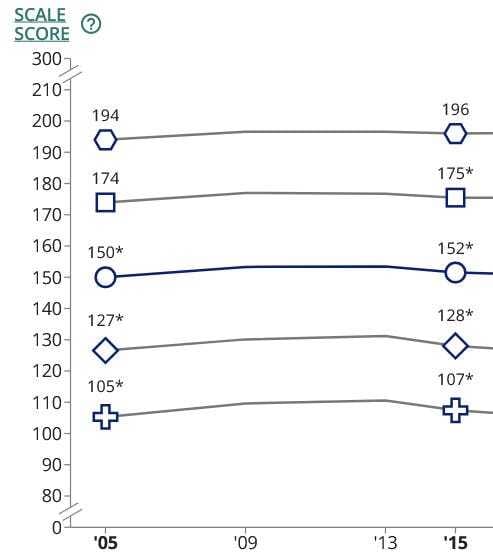

Number go up! 12th graders in the 10th percentile knew two more maths in 2015 than 12th graders did in 2005. 12th graders in the 90th percentile knew two more maths than 12th graders did in 2005. For a cost benefit analysis proponent, Matt sure seems happy that we spent billions and billions of dollars overhauling our nation’s schools for a 2 point gain. But, I also don’t think it makes sense to compare different groups of 12th graders because they had different amounts of time in school under NCLB. The 2005 12 graders had barely 3 years in school under the law while the 2013 cohort had ~8 years in school under the law. The correct way to use NAEP to evaluate Matt’s claim is to look at a single cohort as they move through the school system.

And when you take a cohort view of things, these moderate improvements vanish. If you look at the 2005 4th grade scores and then the 2009 8th grade scores and then the 2013 12th grade scores, you are capturing the same cohort of kids as they age through the school system and take a NAEP every 4 years. What does that look like? Well, it’s hard to say using the actual numerical scores because you obviously don’t give 4th graders a 12th grade test. Instead, we should look at the percentage of kids scoring at least basic and at least proficient each time they took the test.

4th Grade Math (2005): At or Above Basic: 80%; At or Above Proficient: 36%

8th Grade Math (2009): At or Above Basic: 73%; At or Above Proficient: 34%

12th Grade Math (2013): At or Above Basic: 65%; At or Above Proficient: 26%

Just for clarity, in case Matt is reading this and needs help understanding the point: the cohort of kids who were in school during No Child Left Behind lost ground as they aged through the school system. Their math proficiency decreased as they aged. NCLB went into effect in 2002. The kids who took the 2005 administration would have had 3 years of NCLB elementary school when they took their first NAEP. Four years later, in 2009, NCLB had been in full swing for 7 years, and they took their next NAEP. 7% fewer students scored at least basic. 2% fewer students scored at least proficient. That year the Obama Administration announced Race To The Top. In 2013, Race To The Top finalists were announced and money under that policy was disbursed to winning school districts. That same year, the cohort that had received 11 years of education under NCLB took the NAEP assessment in mathematics once more before they graduated and went out into the world (these kids are now in their 30s by the way). 8% fewer students in this cohort scored at least basic than they had four years earlier. 8% fewer students in this cohort scored at least proficient than they had four years earlier. Finally, in 2015, the Every Student Succeeds Act passed and devolved accountability decisions back to the states. At no point was this cohort of kids taking a NAEP test without NCLB being the law of the land. They lost ground every time. This is what we’re supposed to consider a success, Matt?

Why doesn’t NAEP report by cohort? They do! There’s a whole data exploration tool you can use to run reports and create graphs. But, for whatever reason, this is never how the data is reported on. We’re always comparing 12th graders today to 12th graders four years ago and 4th graders today to 4th graders four years ago. It’s not totally useless but if you want to understand the longitudinal effects of a policy like NCLB, you need to follow a cohort of kids as they progress through school systems being run under NCLB’s rules and regulations. Comparing 8th graders in 2009 to 8th graders in 2005 makes no sense as a method to judge NCLB because the 8th graders in 2005 had only 3 years of NCLB while the 8th graders in 2009 had 7 years of NCLB. That is, they had different dosages of the treatment!

Moreover, by cutting off the more recent test administrations we can rule out things like ubiquitous smartphones and social media because they had not sufficiently penetrated schools and youth by 2013. Some people trace the turning point on teen mental health to 2012, for example. So, it’s not just that NAEP declines predate the pandemic, as Matt correctly points out. When we look longitudinally at a cohort of kids, we can see declines in proficiency also predate modern phones and social media usage (not that those things have helped, just that the case that they’ve hurt is not a slam dunk from the perspective of NAEP scores).

Bipartisanship Claims Are Overrated

And what of Matt’s other claim, that repeal of the oh-so-successful NCLB was a bipartisan political move? When Matt includes a link for his claim that dismantling NCLB was bipartisan, it is to another of Matt’s articles. That article does not include much in the way of data about how the public felt toward NCLB, but it does include his own view that Ted Kennedy pursued repeal because he could make political hay out of a seemingly corrupt connection between the Bush admin and curriculum publishers and blame cast on teachers’ unions for opposing testing.

I’ve rehashed this again and again recently but let’s do an overview.

Parents disliked federal and nationwide standardization initiatives such as NCLB, RTTT, and Common Core because they felt (correctly) that it damaged local control of schools. Parents and the general public who identified as conservative or as republicans were more opposed to these than those who were liberal or democratic identifying.

Parents didn’t mind standardized tests but wanted to see less time spent on testing and to feel like tests told schools and parents something useful and actionable about their child. They even went so far as to support teachers’ at their local school in striking to gain more control over testing and curriculum.

There seems to be a link between parents feeling like they don’t have a say in their kids school and wanting to use vouchers to purchase private education.

Opposition to the Evey Student Succeeds Act was 100% Republican in the House of Representatives and in the Senate. So, in a sense, Matt is right that some Republicans and all Democrats voted in favor of ESSA, making it bipartisan, but it was Republicans such as Lamar Alexander and John Kline who were instrumental in its passage. Moreover when Speak Boehner suddenly resigned, the entire house GOP’s support looked like it would collapse. Paul Ryan ended up performing a lot of legislative maneuvering to rebuild Republican support in time to pass the bill. It was Democrats, let by Patty Murray, who pushed for the removal of a series of testing exemptions for kids with disabilities. You read that correctly! Democrats worked to make sure that students with disabilities would not be able to be exempted from standardized tests. Yet we are supposed to believe Matt when he says it’s the left who think tests are racist and want to get rid of measurement?

Scott, Murray and the White House all wanted to preserve testing students each year, break out data on test results to show achievement gaps and use that information to determine when a school needs to change — as a clear way to ensure poor and minority students don’t fall through the cracks in the system. And they wanted requirements that low-performing schools work to change. This was civil rights advocates’ point of view, and they worked closely with the White House and business groups such as the Chamber of Commerce to advance it.

Politico has a great breakdown of the passage of ESSA that includes some key context about which states were creating pressure on their elected representatives. It’s not deep blue ones! Popularism at work:

But constituents in Tennessee and elsewhere had long been crying out for changes to No Child Left Behind. And Alexander, a former U.S. education secretary for President George H.W. Bush and the son of a teacher, plowed forward.

While Matt was technically correct that passage of the law was bipartisan, I just don’t think any of this muting of Bush-era reforms would have been possible if conservatives hadn’t been pressuring their elected officials for those changes. Democrats didn’t have the majority they needed to pass the bill on their own.

It’s also pretty clear that it was an odd-bedfellows combination of conservatives and actual far left advocacy groups that wanted to end the testing regime while the Obama administration and mainstream Democrats worked to keep it. Framing ESSA’s repeal of NCLB as a victory for people who want to end educational measurement and think achievement gaps are racist is wildly out of step with the political haggling being done to pass the ESSA and the work done by Democrats to keep testing in place and ignores the fact that the ESSA preserved all of the testing from NCLB.

Dumb Not Wrong

Still, after all this disagreement on the specifics, I think Matt is correct about some important big picture things.

on some level we’re suffering mostly from a big national failure to take the educational goals of the school system seriously

I agree! We, as a nation, are at cross purposes for much of our schooling. In fact, it’s one of the very first things I wrote when I started Scholastic Alchemy last January:

It’s about the state of play right now and how I believe our system of education arrived at this point. Do I think schooling has purposes beyond job preparation? Absolutely! One thing the pandemic made clear is that schools are, if nothing else, a place to warehouse children so their parents can work (hey, look, another economic imperative). One of the most fascinating things about the conservative rebellion sweeping school systems is that conservatives seem far more able to articulate different ideas about what school is all about. For example, it might be to instill western values, a sense of patriotism, or encourage civic-mindedness among the populace. Perhaps schools are a sorting mechanism whereby the best — whatever that may be — are given more resources and support with the expectation that they’ll have the biggest positive impact on society. These ideas and more are out there actively circulating and, I’d argue, will be influencing education for many years to come.

If you read that Harpers article a month back, you can see clearly that conservatives have put forward a new vision of what and who education is for. Liberals and Progressives, meanwhile, seem unable to articulate a cohesive vision of what schools are for. Nor have they been successful at convincing parents that local control will be an important component of their ideas for the future. So long as we don’t put forward a credible, attractive, and effective alternative to sweeping privatization, we’re going to have a system of schooling that looks a lot like America’s healthcare system, including one with all the information asymmetries and variable quality and access. Sounds less than stellar. Despite my misgivings, Matt Yglseias is right about students.

Thanks for Reading!