- Scholastic Alchemy

- Posts

- Not the Disruption you're Looking For

Not the Disruption you're Looking For

What happens when your school is flooded on test day?

First, some housekeeping. Welcome to Scholastic Alchemy, a twice-weekly newsletter where I write about education and share a handful of interesting links. We’re at an interesting point in American education, one in which everything we thought we knew about schooling seems to be going away. I want to write about that, and other topics in education that I find interesting. If you’re interested in this kind of thing, please subscribe. I plan to put up the paywall in March. If you do not like Substack as a platform, I will be publishing a parallel version using Beehiiv.

School Doesn’t Have to be Bad

I think my readers might look at how I write about schools and think that I don’t like them very much. I say things like “school is about controlling people” and tend to argue that schools are inherently conservative institutions meant to maintain the status quo. And I believe those things! It’s just that that’s not all I believe about schools. I write about the control stuff because I want to make it clear that schools don’t have to be good for kids, their parents, or the well-being of society at large. If we want schools to be good, then it is up to us to make them good. They will not do it on their own because schools are meant to serve as a system that limits change to whatever is acceptable by elites, even in the US where we (used to) pretend that we didn’t have strict social hierarchies.

Today’s post is an attempt to point toward some positive things schools can do in the face of disruptions to education. It’s a dark post because of the nature of these disruptions — fires, floods, pandemics — but ultimately a call for people who care about schools to see them as more than human capital inculcating machines. Indeed, even the social stability function of schools that I call conservative is useful in times where communities are impacted by disasters. Anyway, I hope that clarifies my feelings a bit more. I initially drafted this a few months ago but I think now is a good time to bring it out, in part because it lets me bring up some curriculum topics near the end that I want to write about next week. On to the post.

Schools close, sometimes for a long time!

I want to emphasize something that should seem obvious. Schools close. Sometimes they close for a long time. There are many reasons for an individual school to close and for a district’s schools to all be closed but the ones I want to talk about today are related to disasters and other traumatic events. The reason I want to address these closures is because we are not seriously grappling with the effects of frequent closures on students’ learning, well-being, or even their safety and nutrition. Likewise, we are not preparing schools and districts for increasingly frequent disruptions to learning or acknowledging that a return to learning includes paying attention to students’ mental health and their material needs during a disaster. When, say, a wildfire tears through a community and burns down homes or even the school, we lose more than a building and we lose more than the chance to learn in its classrooms. I think we continue to see such disasters as random and rare when they are anything but. Given the new administration’s work to strip all mentions of climate change from government work and limit funding for anything related to taking climate change seriously, it seems like ‘we’ may continue to talk about disasters as being random. And, I think we continue to design education policy, write curriculum, and implement plans as though we can expect conditions in which most kids to show up every day, on time, and ready to learn for the 180+ days of the school year.

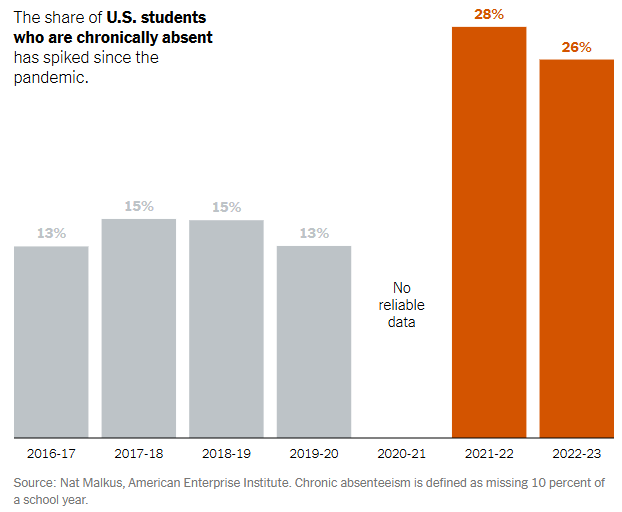

One way to think about how disruptive a closure can be is to compare it with chronic absenteeism. In the wake of the pandemic, we (meaning teachers, parents, school leaders, policy makers, education-related people) have seen increasing alarm around chronically absent students. The numbers are disturbingly high, although they were too high before the pandemic too! Here’s a recent chart based on data put out by AEI:

Now, look, I know AEI is right-leaning and won’t hesitate to slam public schools whenever possible, but I think this data is largely accurate regardless of what conclusions they draw, and it fits with other data saying similar levels of absence exist. Realistically, we’re looking at somewhere between 1-in-4 and 1-in-5 students nationwide missing 10% of the school year or more. If you are a teacher and you have 35 students in your class, that means, on average, 7-8 kids in your class are chronically absent from your class. This is all pretty scary on its own but I want to draw your attention to the threshold for missing school: someone is chronically absent if they miss 10% of school days. 10%. In a 180 day calendar, that means a kid has missed 18 days of school. And there’s all kinds of bad effects that can happen when a kid misses 18 days of school.

Apply that same framing to school closures. We do not think of schools as being “chronically closed” if they’re closed for more than 18 of their normally scheduled days but perhaps we should. Hurricanes Helene and Milton in the fall of 2024 closed some schools for over two weeks. So, we’re almost there! If Pinellas and Hillsborough County schools are closed for even four more days this school year, they’re “chronically closed” for their tens of thousands of students. Many schools in western North Carolina were completely destroyed by flooding from the same storms and remained closed for up to a month in some cases. I’m not saying they should be open! Please do not mistake this as some kind of condemnation of schools for being closed following a natural disaster. Instead, I want to point out an important difference in perspective here. When students are chronically absent, it’s seen as a national crisis that deserves a broad response from many different stakeholders. When schools are chronically closed, the focus is primarily on reopening the school as fast as possible to resume learning as usual. Repair the buildings. Replace the materials. Get butts in seats again. If you can’t, deploy remote learning solutions.

Likewise, when students are chronically absent, we see equal attention given to factors outside of the school. Is there a transportation issue? Do parents care enough to pressure an unengaged child to attend? Or are they working double shifts and just can’t because they’re not home? Has there been some kind of problem in the neighborhood? Perhaps gangs or a shooting? But, when schools are chronically closed, we do not always get a broad perspective of the school as embedded within a community. What is an open school building when students and teachers may have had their homes washed away or burned out? Is it still somewhere we expect rigorous learning to happen? Or, as I argue, do we need schools to be seen contextually as part of and responsive to the community fabric? And, crucially, are we willing to provide support for responses beyond the academic ones? FEMA (if it continues to exist) has a broad remit to provide aid in disasters but one thing we don’t hear about is how they work to bring schools back into functioning. I worry that these kinds of responses are largely local and therefore not considered in larger policy discussions.

We have to expect education disruptions to continue and to increase in frequency, duration, or both.

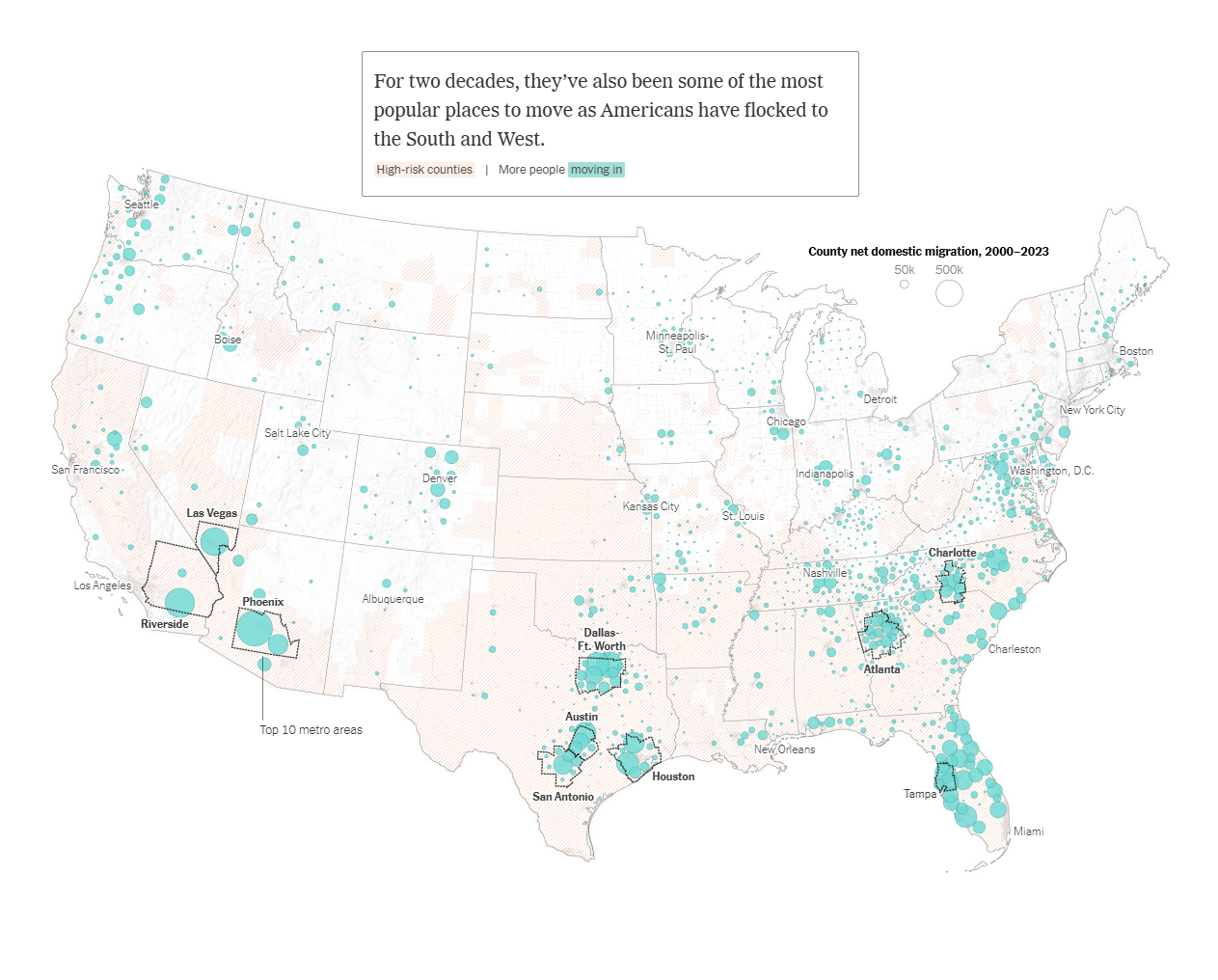

The NYT recently published a look at how the population in the US has, for at least the last two decades, been shifting into counties that are more at risk for natural disasters than where they’ve lived previously.

Seems bad!

One of the key takeaways from the article is that global warming is increasing the number of disasters as well as the severity of disasters and this is expected to disproportionately impact the places where people are moving. While the article does not explicitly mention schools, I think we can safely assume that schools are not somehow immune to the tornadoes, hurricanes, fires, floods, and/or extreme heat impacting their communities. It is irresponsible not to expect the frequency and duration of interruptions to schooling to increase in much of the US.

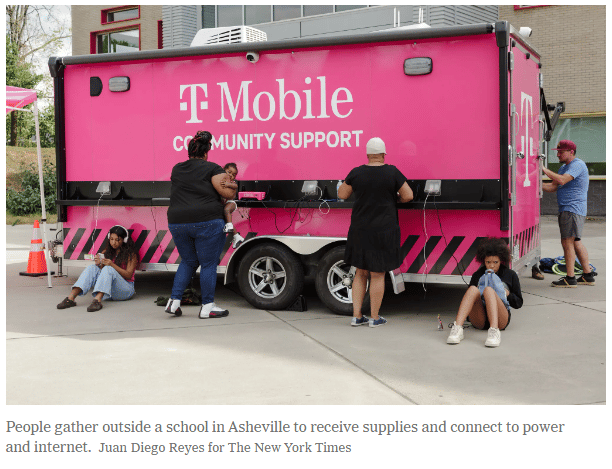

But, when we see reporting on responses to disasters, we get something like this:

We learn that schools’ disaster plans largely revolve around remote learning if the buildings can’t be used for one reason or another but also that those plans are inadequate. When homes are destroyed, roads and bridges washed away, and family members lost to disasters like what we saw in western North Carolina, ensuring students can connect to online lessons seems like an unnecessary focus. At the very least, maybe it needs to be, I dunno, 5th on the list of priorities? Yet, one of the main things that comes up is using mobile cellular and power stations like the ones above, to get kids learning again.

Trauma response

This focus on returning to normal and returning to learning is typical but misplaced. Indeed, we have a lot of research to show the impacts of a disaster are long lasting and require more than “back to normal” type responses. For example:

One of [Boston College researcher] Lai’s studies, for example, found that eight months after Hurricane Ike, more than 40 percent of children reported ongoing sleep problems. Another of her research projects linked Ike with a lack of activity among kids. And in a third study, she found that students experienced post-traumatic stress and elevated anxiety after 2005’s Hurricane Katrina, leading to an increased likelihood of trouble at school.

We need to remember that after Katrina, about 50,000 kids never returned to the NOLA school system. While about half of those were later located as having moved to other states (one was a student of mine at one point), we never discovered what happened to the rest. Somehow, giving these kids a Chromebook and cellular hotspot so they can participate in remote learning doesn’t seem like enough. Merely restarting school as soon as possible without addressing the community-wide problems does nothing for kids who need psychological support, just as it does little for kids who find themselves newly homeless. They have shelter for the day, but what good does that do them at 3pm when school is done?

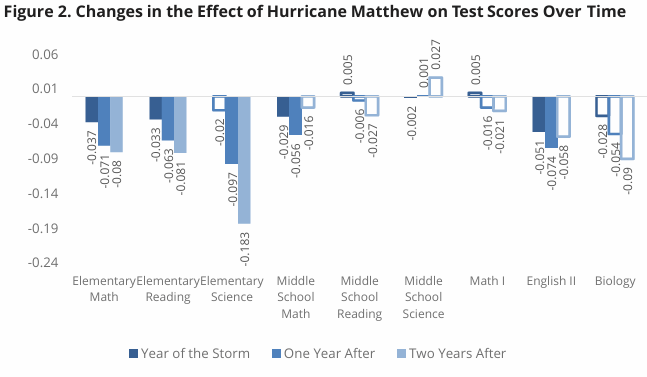

Indeed, researchers at UNC have documented some of the absurdity of our educational response to disaster. In one case, following hurricane Matthew in 2016, UNC researchers recommended exempting affected schools from accountability measures. That’s right! Sorry your students lost homes and your school is flooded out, but you need to make adequate yearly progress or the state will label you failing and fire your teachers and administrators.

The same research shows that students do not academically recover from these kinds of disruptions quickly. Affected schools’ test scores (because they still have to take the tests!) remained behind for at least two years (possibly longer but that’s as far as the study looked).

Note the unshaded boxes on the right are findings that were not statistically significant, indicating that disruptions are probably most impactful at the elementary level. However, some of that lack of significance is due to, you might have guessed, disruptions in testing decreasing the number of takers because there was another more severe hurricane, Florence, two years later.

We can know what school-based disaster response needs to look like by knowing what it does not look like.

One of the reasons I like being a curriculum guy is that everything is curriculum. It’s not just the books and lessons and skills and content that we teach. Curriculum lives in the spaces we teach in. It’s part of our affect as teachers. It’s in the kids’ relationships with each other. Things we choose to exclude from the classroom or the hallways or the textbooks are still pedagogically active in our learning environments. Their absence and exclusion teach kids something, too. This is where we find the ideas of the hidden curriculum and the null curriculum most impactful. Put simply, the things we leave out tell our students something about what we value and think is important. Our students see this and learn something from it. Sometimes these powerful lessons run contrary to the lessons we want to teach and undermine our efforts.

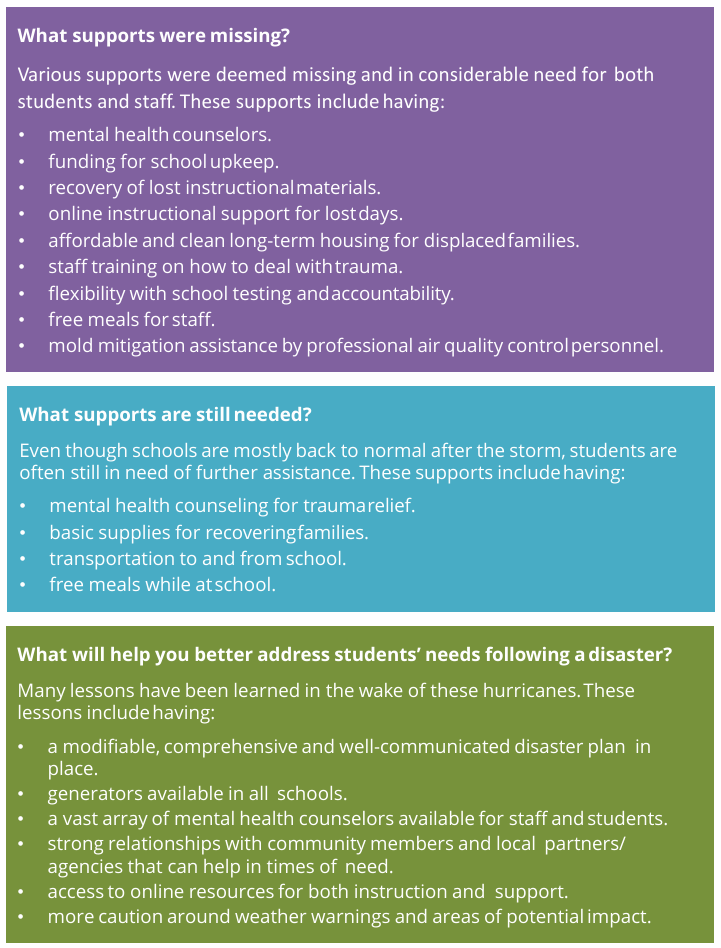

When schools respond to disasters by attempting to return to schooling as usual, I want to think about that as a curricular act. When schools center their academic functions during disasters, they are, whether they intend to or not, decentering other important functions they could fulfill. In another report of their research, the folks at UNC lay out some of what they think schools could be doing to better support their students after disasters. In the list below, how much of that support is academic?

Note we see the mention of school accountability again. Our education laws weren’t written with disruptions to education in mind!

Remember, things we exclude tell us about what schools/districts/states do not value. The above is a list of what schools are not doing or not doing enough of. When kids go back to school and do not have adequate mental health counseling, do not have materials replaced or clean, mold-free facilities, or are asked to take a state test covering content and skills they never learned because of the disaster, what are they learning about what school system considers important? If you needed help because of a natural disaster and all anyone cared about was your score on an algebra exam, how would you feel? What would you think about school? If you can’t get to school because the bus can’t traverse the damaged roads and your car was swept away, does it help or hurt when the school sends your mom automated truancy notifications? Do you think the people in the College and Career Readiness Center (that’s the thing we used to call a counselor’s office) are here to talk about your trauma?

I’m going to leave it here because I think the point is made. We’re so focused on academic outcomes that, as a society, we’ve forgotten that schools need to respond to more than just our students’ academic needs. The disasters aren’t going to stop. Indeed, returning to “normal” might never actually, truly be possible given the increase in frequency and severity of natural disasters and the long lasting impacts of these events on students’ well-being. Throw in other traumatic events - school shootings, economic-induced homelessness, international migration and asylum, and we have to expect our students and our schools 1) to have more disruptions to their learning and 2) to require more material and psychological support than we are currently providing. Pretending like schools will just continue on as normal is no longer an option.

Thanks for reading.