- Scholastic Alchemy

- Posts

- School Accountability Never Died

School Accountability Never Died

And I don't know why people keep saying that

Welcome to Scholastic Alchemy! I’m James and I write mostly about education. I find it fascinating and at the same time maddening. Scholastic Alchemy is my attempt to make sense of and explain the perpetual oddities around education, as well as to share my thoughts on related topics. On Wednesdays I post a long-ish dive into a topic of my choosing. On Fridays I post some links I’ve encountered that week and some commentary about what I’m sharing. Scholastic Alchemy will remain free for the foreseeable future but if you like my work and want to support me, please consider a paid subscription. If you have objections to Substack as a platform, I maintain a parallel version using BeeHiiv and you can subscribe there.

I’m just back from Arizona where I had the honor of standing in a wedding for one of my good friends, a math teacher. While the wedding was lovely and emotionally poignant at times, this isn’t a post about my social life. As you might expect, there were several teachers in attendance and three in the wedding party. This afforded me the chance to not just hang out and do wedding stuff, but to learn a bit about teachers who work in four different states and in four different kinds of schools. Between the four teachers, I heard about urban and suburban schools in both red and blue states. The teachers taught high school math, middle school social studies, and middle school ELA. It’s always nice when you’re a step or two removed from K-12 classrooms as I am, to find ways to check in and learn about schools that you don’t normally get to see if you’re observing student teachers or conducting research. Because so much research is ignored by classroom teachers, it’s incumbent upon people producing research to make it relevant and practical. Unfortunately, we don’t do that well enough. There seems to always be a gap between theory and practice, knowledge based on research and knowledge based on experience. I don’t believe that gap is actually real but constructed by the structure of our systems of higher ed and K-12.

The reason I bring all this up is because teachers and others related to the world of education often see the day-to-day reality of schooling very differently from researchers or policymakers or the general public. Something is lost in translation between all these groups and everyone seems to come away with a different understanding of schooling. After talking to these teachers and reading several different takes on schooling over the last few weeks, I noticed one particular difference coming up again and again. People talking about education policy, especially at the state or national level, insist that ESSA ended school accountability in 2015. Because school accountability is gone, they tell us, there’s nothing making schools teach kids effectively. Apparently having piles of well-meaning capable adults working with children every day to help them learn doesn’t count unless they’re working under the constant threat of termination. People writing from this perspective focus almost exclusively on standardized tests as the core accountability mechanism. You give the kids a test near the end of the year and that tells you if the teacher did a good job of teaching those kids the things they were supposed to know. That, for this group, is what accountability looks like.

Reports of the death of school accountability…

David Frum recently interviewed George W Bush’s former education secretary, Margaret Spellings, and she had quite a bit to say about the need to “bring back” school accountability.

we were getting results, and then we took our foot off the gas. And what does that mean? And you’re absolutely right, it happened—those declines started well before COVID.

And when I say “take your foot off the gas,” what I mean is we stopped paying attention to what I call the fine print of school accountability. We were in the early days of what I call the era of local control—and I’m big for local control—but we allowed states to really walk back on the muscle of accountability, the muscle of assessment, the transparency, and the consequences for failure. And we started to see the effects of that: drifting and flattening and then declining student achievement.

As far as takes about the “end” of accountability go, this is at least given with some qualifications. She’s right that decisions about accountability were returned to the states but notice two things. First, she asserts that states walked back accountability measures, but I don’t see any evidence of that fact in this interview. Second, you have to remember that one challenge every state faced under Spelling’s leadership was the requirement to have 100% of students at grade level in math and English by 2014. That is, to put it simply, impossible. Schools couldn’t do the impossible, so they began to face penalties under the Bush-Spelling accountability system. The waivers and the ESSA were a way out of that quicksand. What Spellings presents as a “walk back” was fixing a bad policy and, just to be clear, republicans were some of the main proponents of repealing NCLB. It’s not just a Democrat thing.

Other commentators, though, have not been as good about qualifying their claims about the death of accountability. I’ve returned a few times to this David Brooks op-ed:

In 2015 Congress replaced No Child Left Behind with the Every Student Succeeds Act. The age of accountability was over; the age of equity was here. Under the Every Student Succeeds Act, states no longer had to produce rigorous report cards on how schools were doing. Most Democratic states watered down the accountability mechanisms.

Last week, I mentioned Idrees Kahloon’s article for The Atlantic that argued we should once more have high expectations for students. With regard to accountability, he told a similar story.

[Under NCLB] expectations for progress rose higher and higher each year, ultimately seeding the demise of the law. Schools were supposed to have all their kids at grade level by 2014. But as this deadline approached, it became clear that schools would miss it. In 2012, the Obama administration began giving states waivers from the requirements. Then, in 2015, Congress passed the Every Student Succeeds Act, which returned responsibility for improving low-performing schools to the states.

This, Kahloon terms, “low-expectations theory:”

In short, schools have expected less and less from students — who have responded predictably, by giving less and less.

It seems that, like Spelling, Kahloon believes that without harsh consequences based on standardized test scores, schools will not try to educate students. The view that accountability is dead is not new, either. Matt Yglesias made a point to mention it two years back and it’s sort of a consensus position among some liberals in politics and media:

Accountability, of course, means standardized tests, requirements that students master reading before they are advanced to the fourth grade, and rankings of schools on performance. Accountability is no fun; when there aren’t active political currents pushing for it, it tends to erode. But it’s badly needed.

I added some emphasis there. Accountability, we are told, only comes from standardized test scores used to judge whether schools and teachers are actually doing their jobs in achieving high test scores. I’ve penned some of my problems with state-level standardized tests and they’re nothing to do with racism or equity. Rather, I think these tests are often low quality and fail to accurately measure kids’ capabilities or provide useful input for teachers to make pedagogical changes or for districts to make programmatic changes.

Here’s a pair of classics where people who’d traditionally been pro-testing had moderated their positions a little bit. First, Jay P Greene of the Heritage Foundation who wrote,

Over the last few years I have developed a deeper skepticism about the reliability of relying on test scores for accountability purposes. I think tests have very limited potential in guiding distant policymakers, regulators, portfolio managers, foundation officials, and other policy elites in identifying with confidence which schools are good or bad, ought to be opened, expanded, or closed, and which programs are working or failing. The problem, as I’ve pointed out in several pieces now, is that in using tests for these purposes we are assuming that if we can change test scores, we will change later outcomes in life. We don’t really care about test scores per se, we care about them because we think they are near-term proxies for later life outcomes that we really do care about — like graduating from high school, going to college, getting a job, earning a good living, staying out of jail, etc…

But what if changing test scores does not regularly correspond with changing life outcomes? What if schools can do things to change scores without actually changing lives? What evidence do we actually have to support the assumption that changing test scores is a reliable indicator of changing later life outcomes?

As loathe as I am to agree with someone from Heritage, this is a good point! Our ultimate purpose in pursuing accountability policies isn’t just high test scores or quality schools but the positive impact we believe chasing those scores will have on peoples’ lives.

Similarly, Fredrick Hess, who was at the American Enterprise Institute at the time, questioned whether rising test scores tell us anything meaningful about a school.

After all, results are what matters.

But that presumes that the results mean what we think they do. Consider: If it turned out that an admired pediatrician was seeing more patients because she’d stopped running certain tests and was shortchanging preventive care, you might have second thoughts about her performance. That’s because it matters how she improved her stats. If it turned out that an automaker was boosting its profitability by using dirt-cheap, unsafe components, savvy investors would run for the hills—because those short-term gains will be turning into long-term headaches. In both cases, observers should note that the “improvements” were phantasms, ploys to look good without actually moving the bottom line.

That’s the point. Test scores can convey valuable information. Some tests, such as the National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP), are more trustworthy than others. The NAEP, for instance, is less problematic because it’s administered with more safeguards and isn’t used to judge schools or teachers (which means they have less cause to try to teach to it). But the NAEP isn’t administered every year and doesn’t produce results for individual schools. Meanwhile, the annual state tests that we rely on when it comes to judging schools are susceptible to all the problems flagged above.

This makes the question of why reading and math scores change one that deserves careful, critical scrutiny. Absent that kind of audit, parents and communities can’t really know whether higher test scores mean that schools are getting better—or whether they’re just pretending to do so.

Note that both articles were written after accountability supposedly died in 2012 with the Obama-era waiver policy. I should note, too, that here we are once again with a pair of conservative voices objecting to standardized tests, and we would do well to remember that opposition to accountability testing may have been somewhat bipartisan but actual movement on the issue depended on populist conservatives breaking ranks with Bush era Republican reformers.

… have been greatly exaggerated

What I find most interesting, though, is that all of these perspectives arguing that accountability is dead depend on accountability being synonymous with standardized testing. If teachers and schools are not punished for low test scores, then they are not held accountable. If you consider all the other things that teachers and schools are held accountable for, though, it turns out that accountability is alive and well. Hell, even accountability testing continues on!

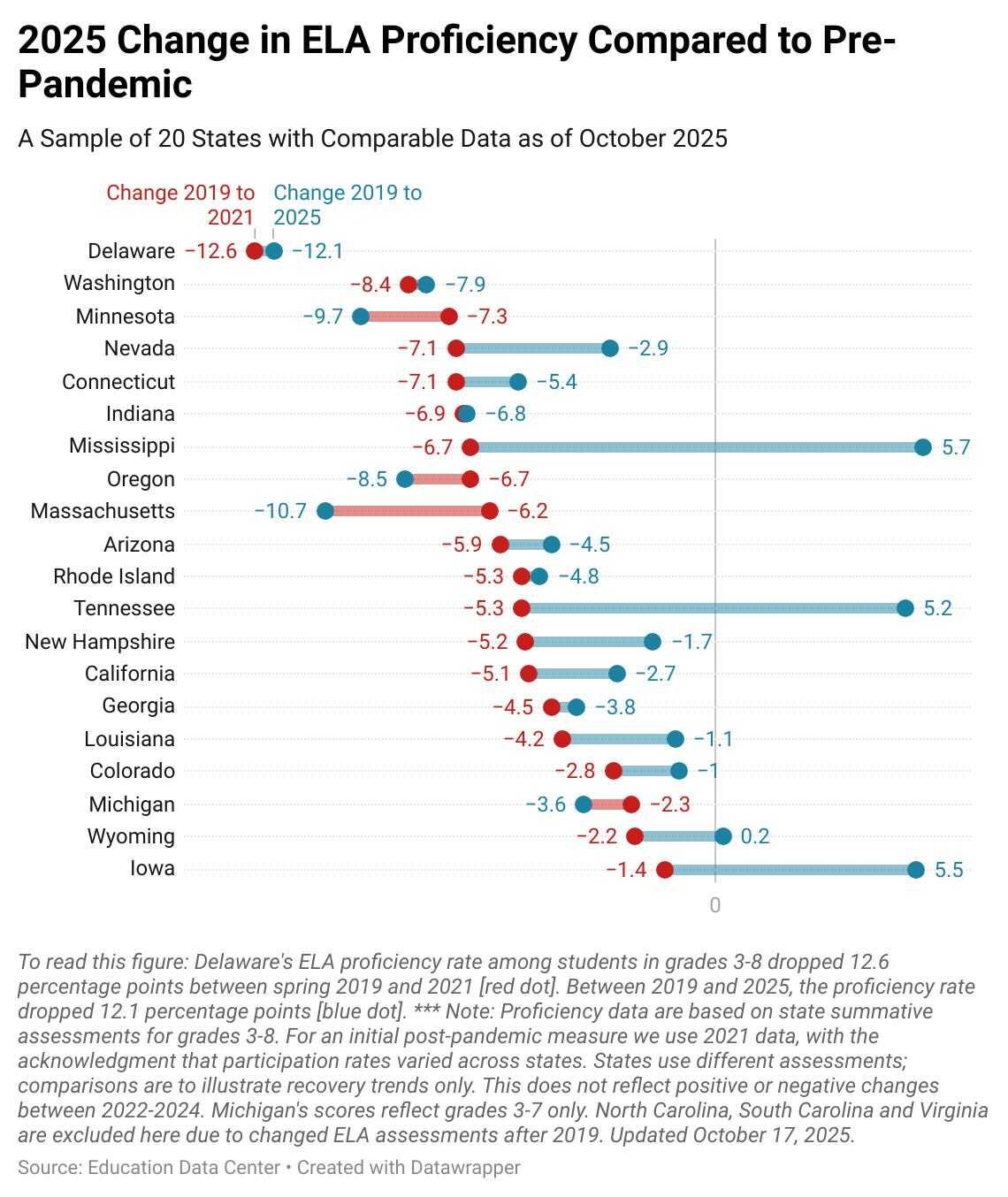

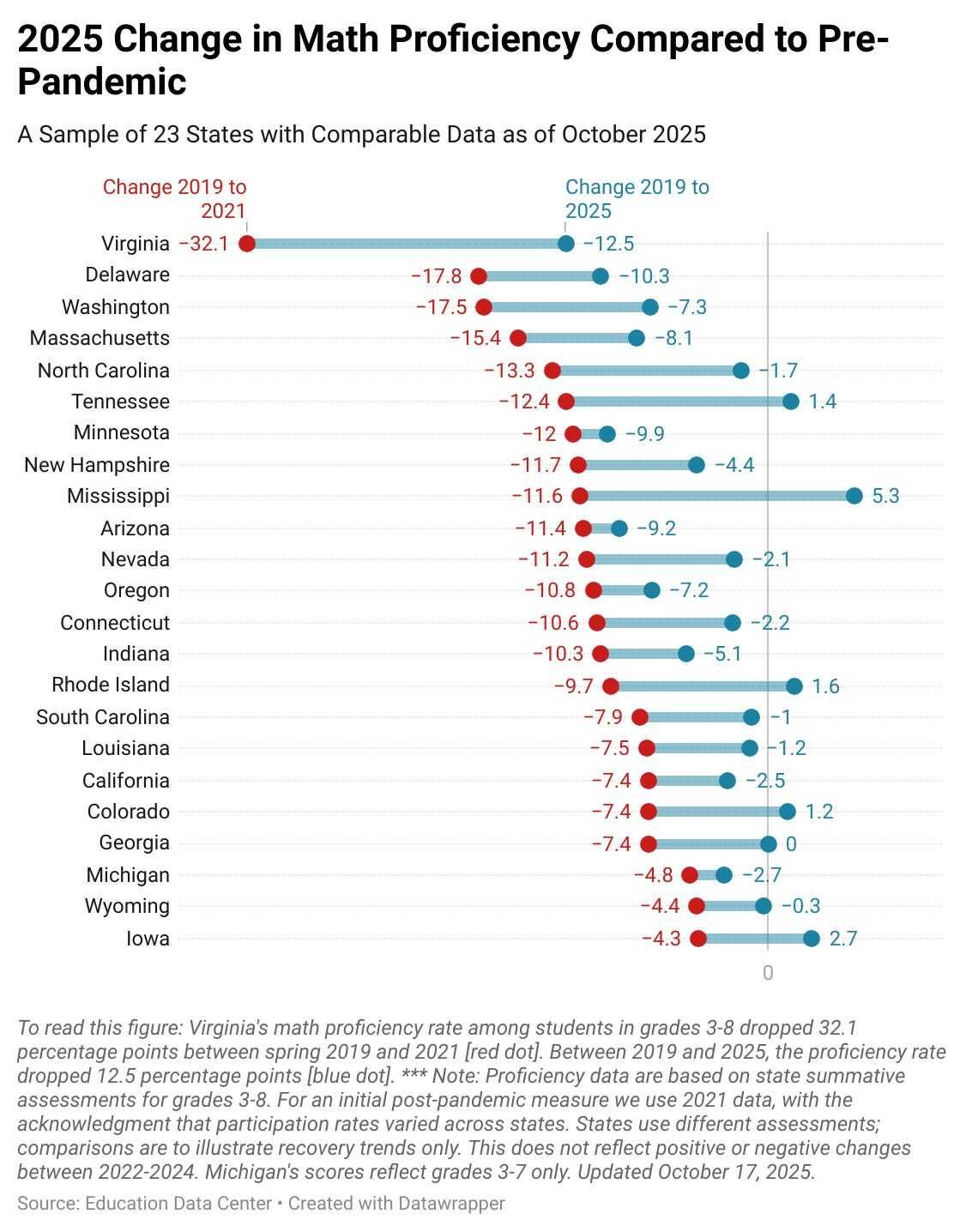

The Education Data Center collects data from state tests. You know, those high stakes standardized tests we’ve supposedly stopped giving? Here’s their data from 23 states that have met their reporting requirements this year. This isn’t to say that only 23 states do testing. EDC is interested in long term trends and recognize that if states change their testing, they can’t make an accurate comparison with scores from previous versions of the tests.

Our sample is limited to states with data comparable to 2019 - in other words, we are excluding states with new state assessments since 2021, as we cannot make valid comparisons to pre-pandemic outcomes.

Emphasis is in the original. Here’s the graphs to summarize the data. Remember these are not NAEP scores administered by the federal government. This data comes from scores on state mandated standardized tests.

Wow, how come no talk of the Iowa miracle. They appear to be doing well in a fashion similar to Mississippi and Tennessee. And once more, nobody talks about miracles in math but look at those gains for Virginia and Mississippi. Math scores are consistently improving more than ELA. Why are we not talking about this?! Anyway, that’s not the point of this post. The point is, if you listened to the complaints about lacking accountability then you might think states stopped testing but, clearly, they did not.

Moreover, it seems like some of the coverage of what changed under the ESSA is, how do I put this, lies. Let’s look at that David Brooks quote again.

In 2015 Congress replaced No Child Left Behind with the Every Student Succeeds Act. The age of accountability was over; the age of equity was here. Under the Every Student Succeeds Act, states no longer had to produce rigorous report cards on how schools were doing. Most Democratic states watered down the accountability mechanisms.

Emphasis added. Now, let’s look at how the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, a professional organization for school and district leadership, described the ESSA changes related to report cards:

9. Will states continue to make data public through annual report cards? Yes, states must still issue annual report cards that include the following:

• A detailed description of the state’s accountability system

• Schools identified by the state as being in need of support and improvement

• Student test results disaggregated by subgroup

• Student participation rates in assessments

• Student performance on other academic indicators

• Performance on the statewide non-academic indicator

• Graduation rates and postsecondary enrollment

• English language learner proficiency rates

• Per-pupil expenditures of federal, state, and local funds, including actual personnel costs

• Results from the National Assessment of Educational Progress

• Teacher qualifications, including those with emergency or provisional status

• The number and percentages of students taking alternative assessments

• Data collected pursuant to the Civil Rights Data Collection survey

States may, of course, collect or include any other information that they choose

Huh, wait, I thought states weren’t doing “rigorous report cards” under the ESSA? Or is this set of 13 criteria not rigorous enough? I see state test scores and NAEP scores there as a requirement. You can look at the government’s own documents that help summarize the accountability changes under the ESSA law and see the ASCD report is correct. States still had to give standardized tests, still had to report scores, still had to develop accountability plans to improve low-performing schools. The accusation is, I guess, that these metrics were gamed by the states so as to make accountability an illusion but it’s not clear to me there’s a case to be made that this was, in fact, the case. Maybe they’re upset that non-academic indicators were included? Let’s see what those might be:

The federal government is prohibited from prescribing the measures that states select, but ESSA does require that whatever measures are selected, they must be used in all schools in the state and “meaningfully differentiate” between schools. States can include more than one nonacademic indicator if they choose do to so. ESSA provides specific examples of possible measures—school climate and safety, student or educator engagement, access to advanced coursework, and postsecondary readiness—but specific ones are not mandated nor must it be chosen from the aforementioned list. Other indicators that are being discussed by educators and advocates include chronic absenteeism, discipline referrals, dropout rates, and access to extracurricular and other enrichment opportunities.

These things are, apparently, not rigorous. We can’t be holding schools accountable for absenteeism or postsecondary readiness or access to advanced coursework. No, what counts as accountability is test scores and only test scores and it is the drop in, wait for it, test scores that tells us we, um, aren’t testing. Did I get that right? The argument seems based on a bunch of premises that just aren’t true. Obama and the ESSA law did not repeal standardized testing and did not put an end to state report cards and did not end school accountability. What it did was shift the oversight to the states.

So, why do so many commentators say that states no longer need to have accountability requirements? If Obama and the Every Students Succeeds Act didn’t remove the rules requiring states to have accountability programs for schools based, at least in part on test scores, then who did? Donald Trump and his Republican allies in Congress. What Brooks and Kahloon and Spellings don’t spend much time on is examining Trump’s ending of the entire system of accountability at the federal level. Because of Trump, there is no federal requirement for states to have any kind of accountability measures in place at all. Many states still do and, as those links indicate, the ESSA requirement to assess students with standardized tests remains in place.

Not Dead But Changed

This brings me back to meeting those teachers at my friends’ wedding. In talking with them I realized something else had fundamentally shifted about our accountability apparatus. Sure, there’s no federal requirement anymore, but states have no abandoned accountability. Indeed, all four assured me they were still quite accountable for their students’ scores on state tests and worried about being fired should their scores ever drop without a good explanation (like a pandemic). The new discovery (for me) was that accountability systems have shifted to curriculum and teaching practices. If these teachers were not following various instructional practices with fidelity, they would be placed on “performance improvement plans,” basically a euphemism for initiating the firing process. This might be following a written script when teaching. It could be not discussing sensitive topics. It might be using the school’s required grading scale that gives half credit even for assignments not turned in. I learned from these teachers that they lacked the agency to resist these policies even though many felt they were harmful for student learning.

Schools still pressure teachers heavily over test scores, in part because those scores go into the report cards that supposedly stopped existing or stopped being rigorous in 2015. Yet, somehow I can look up school “report cards” for pretty much any school anywhere. You want a 55-page detailed breakdown of a school’s performance? Here’s an elementary school in New Jersey. You want a detailed webpage with A-F grades across a variety of criteria and detailed tables of state test results? Here’s a random high school in Texas. Are these not “rigorous reports cards.” Are we supposed to assume schools don’t care about these outcomes when states, even blue ones where allegedly rigor and expectations have vanished, are holding schools accountable for low performance?

Teachers across America have been working under systems of standardization and accountability for nearly three decades. While top-level leadership and policies have changed repeatedly, it seems like the daily reality of teaching remains largely the same. You, as the teacher, are the one on whom students’ performance on state standardized tests rests. Because entire schools are still held accountable for students’ performance, you need to teach exactly what the school says in exactly the manner the schools says you should teach it. The high test scores depend on it so the school’s continued existence depends on it. I’ll close with what I wrote in response to Adrian Neibauer’s newsletter in last week’s links. You should really read his post to get a sense of what accountability actually looks like in practice.

We air complaints of kids being unable to read whole books or even longer passages. We hear that they can’t hold complex thoughts and need extensive support in navigating multi-step assignments. We’re told they are happy to cheat with AI because they don’t feel like doing even moderate workloads. Adrian has, perhaps, been lucky that this harsh new standardized reality is new to him while many others around the country have been teaching and learning in this way for years.

When I wrote that the people hate standardization, this is what I had in mind. There’s always so much focus on standardized testing, which some people don’t like and will opt their kids out of, but the larger underappreciated problem is the changes that accountability testing brings to the classroom. While I may have said, “it’s the tests stupid” what I mean isn’t that the tests themselves are always so objectionable. Instead, parents and the public dislike schools where the paramount value is producing high test scores. What’s more, because the tests are seen as external to the school, parents see themselves as losing control of what’s happening in their ostensibly locally controlled schools. Kids aren’t happy. Parents aren’t happy. Teachers aren’t happy. Nobody’s learning anything real, merely test skills. But, this all serves a larger purpose. Here’s what I said at the end of August.

Parents do not equate standardization and testing with rigor and quality. When public schools become focused on standardization and achieving high test scores, parents see this as bad and become more receptive to alternatives. Anti-school conservatives are there, ready to take your kid to Disney to learn fractions from Snow White on the taxpayer’s dime. And, it appears that parents are willing to take on the burden of being the executor and guarantor of their children’s education if it means they escape systems of testing and standards.

While test-based accountability remains, the way it is operationalized has shifted. We now see highly prescribed forms of teaching requiring “same way, same day” adherence, scripted lessons, and regimented, segmented curricula focused exclusively on isolated skills. None of this is new exactly, but it is now even more commonplace than before. We are teaching to the test more than ever, enabled by digital learning systems and AI generated testable-skill passages often made by the same companies that produce the tests. Teachers are under more pressure than ever to look and sound exactly right, down to their mannerisms and cadence of voice. Lessons have to look the same everywhere because that’s what district leaders think will lead to those scores.

We’re told again and again that the era of accountability is over and that it’s all Obama’s fault for ending NCLB and sending accountability back to the states. Here in the real world, we remember the impossibility of achieving 100%. In the real world, we remember that Trump and Republicans ended the accountability measures in the ESSA. In the real world we also still live under a testing and accountability regime that asks for near-total compliance down to controlling our very muscles and speech. Accountability is alive and well. Insisting otherwise is simply lying.

Thanks for reading!