- Scholastic Alchemy

- Posts

- School is about controlling people

School is about controlling people

schools are more conservative than people think

First, some housekeeping. Welcome to Scholastic Alchemy, a twice-weekly newsletter where I write about education and share a handful of interesting links. We’re at an interesting point in American education, one in which everything we thought we knew about schooling seems to be going away. I want to write about that, and other topics in education that I find interesting. If you’re interested in this kind of thing, please subscribe. I plan to put up the paywall in March. If you do not like Substack as a platform, I will be publishing a parallel version using Beehiiv.

My kid is “in the system”

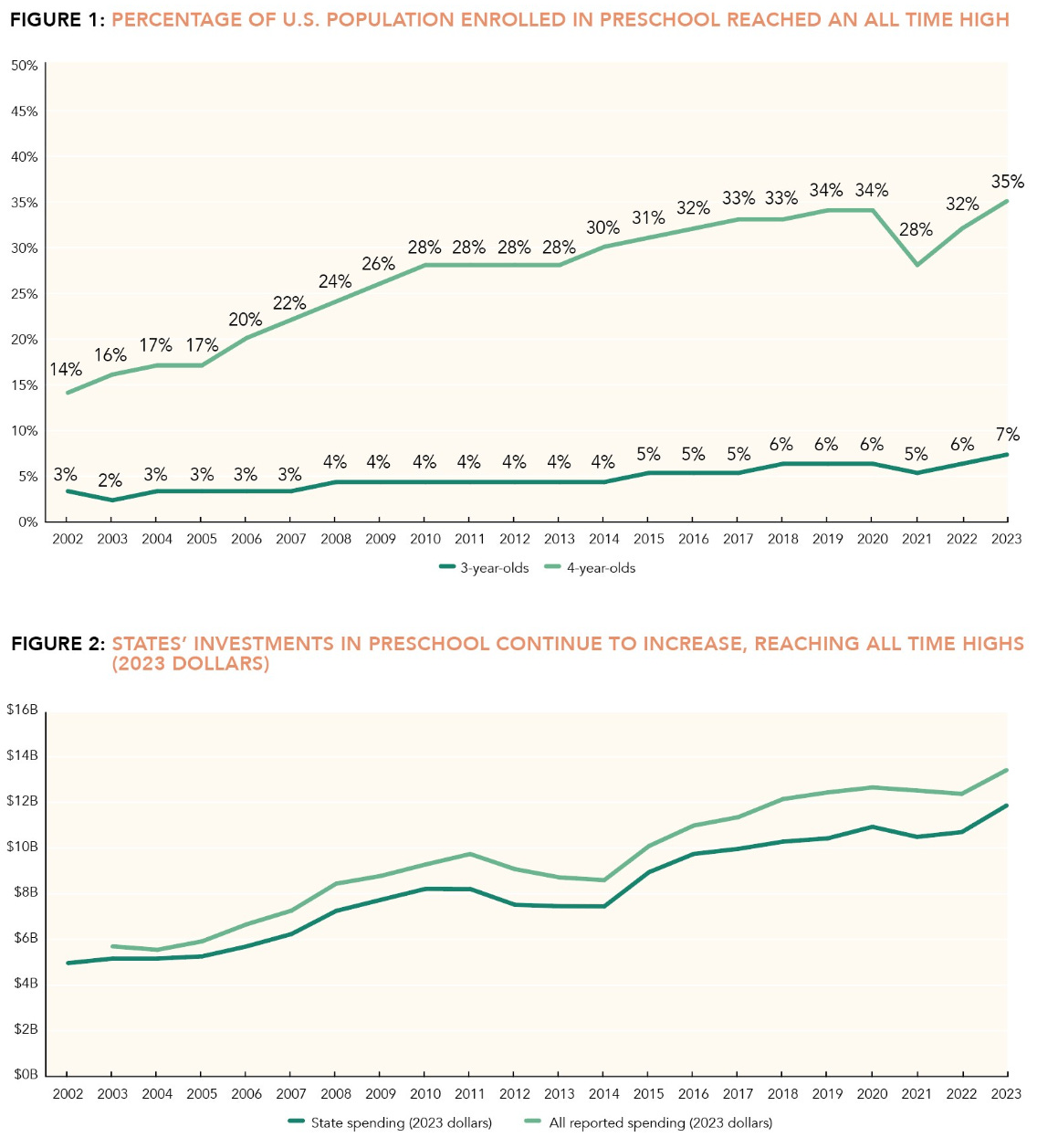

Universal prekindergarten programs are popular and expanding around the country. States as different and diverse as California, New Mexico, Colorado, and Alabama have increased funding for their pre-k programs, some introducing universal options. It’s one of the few areas where there seems to be bipartisan agreement to expand early childhood programs and pay for them.

source

As someone who believes that high quality early childhood education is good for kids, we’ve been paying to send my kid to a local daycare part-time even though I could ostensibly stay home with her full-time and do all the rearing myself. The city I live in provides free 3-k and pre-k to all parents by levying an extra tax on the top 3% of income earners. So, next fall, she will enroll in the city’s 3-k program, hopefully at the same childcare center where she’s currently in daycare. Ahead of enrollment applications I set up an online account with the city’s public schools and I went to visit the center and hear about their 3K program and what I could expect for my daughter. Since the city funds it, the city provides the curriculum, randomly inspects the childcare center, and oversees various kinds of compliance.

They emphasized a few things. One is the absolute importance of timely arrivals that we parents need to ensure. Another is that kids’ autonomy is a big part of the program for three-year-olds. They need to be able dress and undress outerwear, take on and off shoes, pack and unpack a backpack, and be fully proficient with various utensils for eating. They’re given a lot of leeway in following their own interests to various learning “stations” set up around the room but also receive some more structured instruction. In order for this to work, the kids will need to be able to manage their little bodies and their very big emotions as they move around a fairly busy room with two adults and thirteen other kids. Therefore, the program includes social and emotional learning components to help kids navigate conflict, control their feelings, and generally not upset the function and flow of the classroom. This is doubly important, we were told, because the expectations are even higher next year in the pre-k program. Later I remarked to my wife that our daughter is in the system. Her trajectory, her pathway to adulthood that includes a large chunk of her life being in a classroom, is now going to be largely subject to the needs and logic of a school system.

Disciplining and Punishing

The above paragraph may not seem bad. Indeed, much of what I’ve reviewed about the curriculum and much of what I’ve experienced with the center’s staff through her time in daycare tells me that the level of control they exercise is only what is absolutely necessary and largely beneficent. While there are those who would probably argue almost any level of control over a child is a bad thing, I’m not in that camp. At the very least we have an obligation to children’s safety and health which may at times necessitate coercion, even physical coercion. There are times where my daughter was about to wander into a busy street had I not physically intervened against her will. Beyond physical domination, parents regularly deploy psychological and emotional indoctrination. I am psychologically and socially manipulating her so that she no longer wants to wander into the middle of a busy street and instead uses crosswalks. This is indoctrination. We don’t think about it that way because it’s something we associate with authoritarian governments and would never happen in America but the whole point of indoctrination is simply to get someone to accept something uncritically. I don’t want my daughter to deliver a precis on pedestrian safety or to understand the importance of visibility differentials on various cars. I want her to stop walking into the street and not to question why but to, instead, accept that she needs to stop walking into the street.

Schools do this too. We don’t want students constantly wandering in and out of classrooms at will, speaking out of turn or cutting off other students, leaving campus without anyone knowing, fighting, doing drugs on school property, or having sex in the bathroom stalls, among many other things. Schools make rules and enforce them with a variety of measures, but the larger goal is not constantly enforcing rules on kids but getting them to accept that following the rules is the right way to be. We want them to internalize the rules, live by them, and accept the values underpinning those rules. Discipline is not the act of punishing someone for violation. Discipline is the subject acting on herself to abstain from undesirable behaviors and enact desirable ones. If you think about this in terms of power, it is an exchange of power between the authority and the subject, the schools and the kids. The school holds the authority and the power, but the goal is to empower subjects to exercise the school’s authority on themselves.

When I say that my daughter is in the system, this is also what I mean. Her behavior, her very way of thinking, will be shaped by the needs of the city’s school system, its curriculum, and the staff at her 3-k center in order to accomplish their goals. Some of those goals are, at best, tangential to my daughter’s adequate growth and development. They are goals related to the system’s need to function smoothly, successfully regulate all kids, and get those kids to act in ways the school needs. Even my life will be regulated by the needs of the school system. I am subject to their drop-off and pick-up times, to their school calendar, and to support their instructional needs both materially and with my daughter’s learning. These are things I am, more or less, accepting uncritically. Okay, maybe that’s not totally true. I am probably the only parent who requesting samples of curriculum materials and reviewed them using what I know about child development, curriculum, and life more generally to evaluate what I saw. It’s fine! None of this is inherently bad (unless you believe the unschoolers). Just because I am fine with the way power works in this instance doesn’t mean I should ignore that this is, in fact, a kind of control being exercised by political authorities in my city, curriculum developers at some company, and by teachers and staff in my daughter’s school.

So, when I say schools are conservative, this level of control, self-perpetuated needs, and intent to discipline is why. To put this another way, schools work to maintain the status quo that keeps them functional. Maintaining the status quo is an inherently conservative proposition, even if the status being quoed is seen as something liberal or left leaning. Schools are meant to maintain the existing social order internally, yes, but they also function in a larger way to maintain the social order more broadly in a nation. Indeed, schools are part of a larger state-building project that maintains the supremacy of governments over their subjects.

It turns out that countries established compulsory schooling in order to better control their citizens. I linked that podcast in last Friday’s links, and I still recommend it because it nicely summarizes Agustina Paglayan’s new book Raised to Obey. I’ve read most of the book and I think Paglayan makes a convincing argument. She directly addresses several alternative theories about the spread of compulsory education, such as democratization or industrialization, and uses a variety of evidence as to why that is not the case. Her thesis, from that podcast, is

what the book argues, essentially, is that the expansion of primary education in the west was driven not by democratic ideals but by the state’s desire to control citizens and to control them by targeting children at an age when they are very young and susceptible to external influence, and to teach them at that young age that it’s good to respect rules, that it’s good to respect authority—with the idea in mind that if you learn to respect rules and authority from that young age, you’re going to continue doing so for the rest of your life, and that’s going to lead to political and social stability and, in particular, the stability of the status quo, from which these political elites who are using primary education benefit from.

All the things we associate with education today, such as gaining useful knowledge and skills, are later add-ons to the primary mission of schooling, social stability. It’s not a huge book but is more comprehensive than I’d expected going in. Paglayan’s data encompasses a variety of countries across the last 200 years and the examples she pulls out are helpful to understand the data more broadly. I can’t recommend it enough because, as she notes in the podcast, her data rehabilitates mic-20th century sociological views of schooling that have somewhat fallen out of favor and been supplanted by more economic lines of thinking (e.g. human capital) in part because their tradition was more analytical and philosophical than data-driven empiricism.

What I want to point out today is something new I learned from reading the book, the difference between nation-building and state-building. I’m not a political scientist or international affairs guy, but it’s something I like to learn about even though I have no formal training there. If you’d asked me last week what the difference was, I wouldn’t have been able to tell you. I had nation-building in mind when I wrote,

Compulsory mass schooling in the west has its roots in the development of nationalism and the need to develop a common identity and shared culture. If you’re going to build a nation, either historically or today, one of the big things you do is set up schools to further your cause. This is one reason I say schools are actually conservative institutions.

What Paglayan made clear to me is that this is not really the root of compulsory mass schooling. The difference is, in fact, less subtle than I may have imagined and it helps explain why it is important to explicitly identify the functioning of state power as well as its goals.

Recently, state-building and nation-building have sometimes been used interchangeably. However, state-building generally refers to the construction of state institutions for a functioning state, while nation-building the construction of a national identity, also for a functioning state.

Compulsory mass education may have been used in many cases for nationalist purposes to help inculcate a unified national identity and unify the citizenry, but that was 1) often implemented later with behavioral/values purposes coming first and 2) ineffective on its own absent the state-building piece. France offers a good example. Immediately after the French Revolution and again during Napoleon’s reign, France attempted to establish a system of compulsory primary education along nation-building lines.

There cannot be a firmly established political state unless there is a teaching body with definitely recognized principles. If the child is not taught from infancy that he ought to be a republican or a monarchist, a Catholic or a free-thinker, the state will not constitute a nation; it will rest on uncertain and shifting foundations; and it will be constantly exposed to disorder and change.

Napoleon I, 1805

As you see from the quote, Napoleon is talking about education in terms of identity: republican, monarchist, Catholic, or free-thinker. The stakes, too, are clear: constant disorder and change, shifting foundations that will make it hard to constitute a nation. And yet, even Napoleonic France lacked the state-building side of the equation. Both of these attempts left much of the provision and financing of primary education up to local towns and parishes. It was not until the 1830s and the July Monarchy brought the bourgeoise into power under a constitutionally limited monarchy that a successful attempt was made along state-building lines. Although they initially had the support of the workers and peasantry, the first several years of their leadership were marred with continual civil unrest that threatened to unseat the wealthy elites.

Their answer was Guizot’s Law in 1833. Paglayan stresses that this was not another attempt to forge national identity but, instead, an attempt at moral suasion via schooling. The idea, expressed by Guizot and his compatriots, was that, like Prussia, they would be “inculcating in young people obedience to the laws, fidelity and attachment to the prince and to the State so that these combined virtues may early germinate in them the sacred love of the Fatherland” (Cousin, 1833). Note the difference here from Napoleon’s nationalist formulation. Obedience to the state is at the forefront of the efforts. It is from this obedience that a love for France will emerge, not the other way around.

Control remains the foundation of education

Despite two centuries of change and growth, control remains at the core of education worldwide. The state has many tools for maintaining control over its population, but we’ve lost sight of the fact that schooling is one of them. Since the 19th century, whenever ruling elites (authoritarian, democratic, and every degree in between) have felt their position at the top of the hierarchy was threatened, they turned to compulsory mass education as a prophylaxis, a preventative measure against future disorder. Even now as my daughter is set to enter 3-k and begin her journey through a school system, the center of what she is set to learn supports her obedience. She, at three years of age, is to follow the rules and procedures, internalized the processes, and accept that her interests are aligned with the interests of the authorities. This seems okay because my interests, my daughter’s interests, and the authorities’ interests are broadly aligned. We’ve come to expect that our government, and especially our schools, ought to mostly serve the interests of the populace. But, if you’ve been following education at all in the last few years, you know that trust is breaking down. Moreover, some at the top of our social hierarchy felt that schools were not doing enough to protect the status quo. Allow me to close with a (long) quote from Paglayan. As you read it, think about how she is noticing ways schools protect those with power and privilege.

One recent illustration of the book’s argument is the wave of curriculum reforms proposed, and in many cases enacted, by Republican politicians following the Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests of summer 2020. I witnessed these protests with deep concern that — like in France or Chile during the 19th century, or Peru in the twenty-first century — they might prompt those politicians who felt most threatened by protester demands to turn to education reform as a mechanism of social control. The concerns began to materialize when at the end of summer 2020 the Trump administration created the 1776 commission, charged with making education policy recommendations to promote “patriotic education,” “better enable a rising generation to understand the history and principles of the founding of the United States,” and “correct the distorted perspective” and “radicalized view” that racial inequalities are the product of laws and public policies. After Trump left the presidency in January 2021, the efforts to reform and “de-radicalize” school curricula turned to the state level, where Republicans, who felt most threatened by the BLM movement’s demand to reform existing institutions, enacted laws to ban public schools from teaching “divisive concepts” such as institutionalized racism.

While we may be tempted to underscore the differences between this and all other cases in the book, Republican elites anxiety following the BLM protests and their subsequent effort to prohibit schools from teaching about institutionalized racism fits well with the ubiquitous phenomenon identified in this book: Elites threatened by mass protest turn to education to teach children to accept the status quo. Nineteenth-century autocrats in Europe were among the first to respond to social unrest in this way, but politicians in modern societies — democratic and not — have turned to similar tactics, too.

p.314

Thanks for reading.